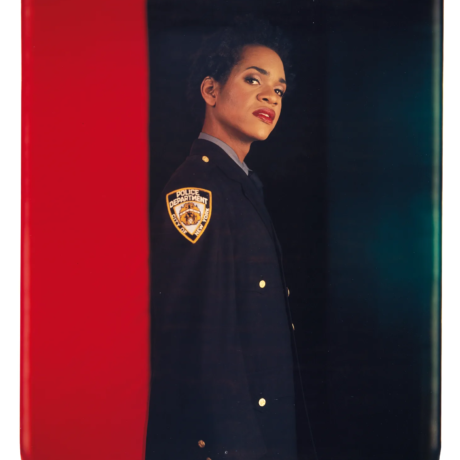

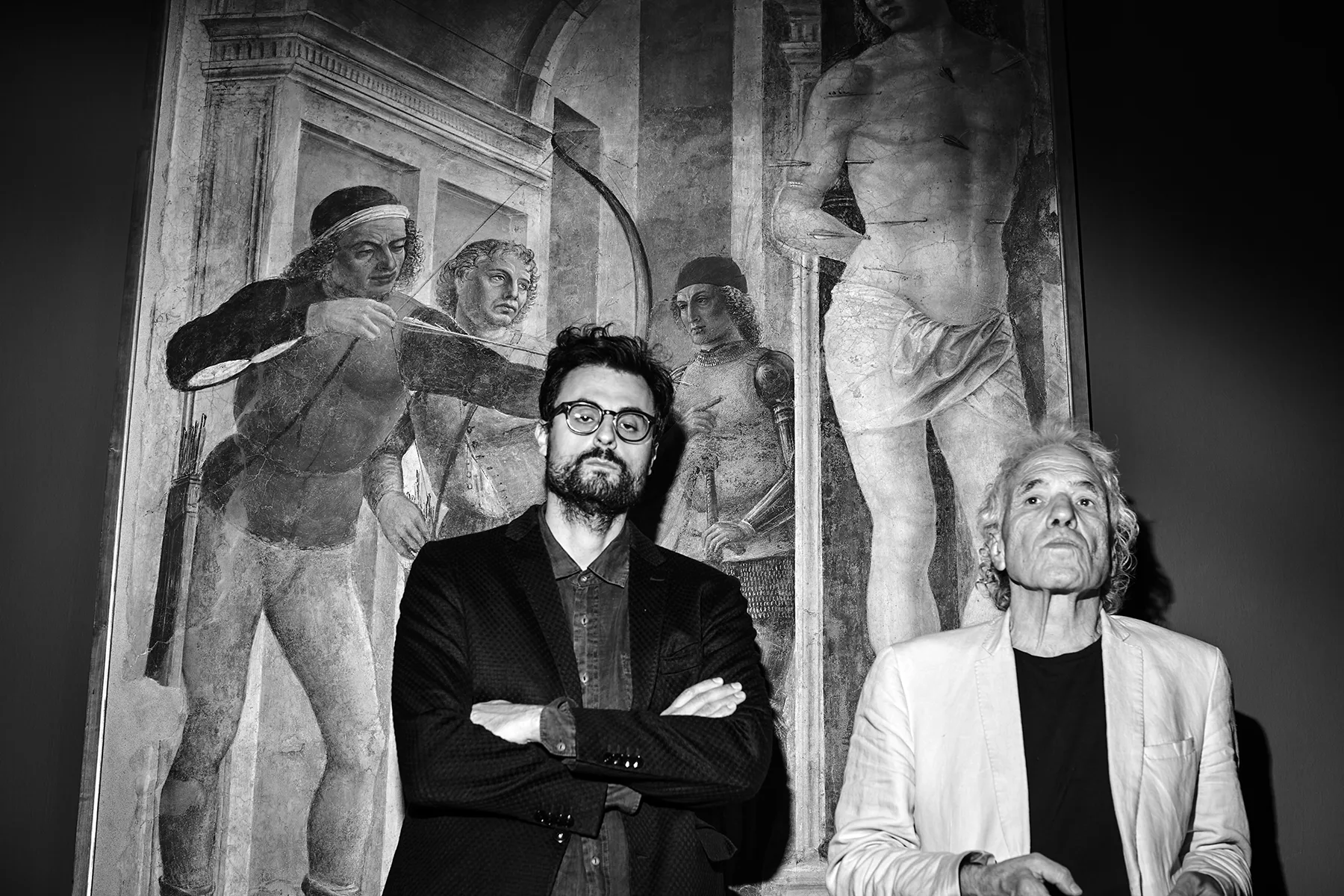

Abel Ferrara and Gabriele Tinti have been collaborating since 2020, bringing readings to museums across Italy, below is their conversation in Rome.

Abel Ferrara and Gabriele Tinti meet once again in Rome on the occasion of Tinti’s appointment as poet-in-resident at the National Roman Museum. The project is intended to deepen the understanding of the Museum’s collection through the involvement of various artists —including Willem Dafoe (who has already recorded a series of readings for this project) and Abel Ferrara— and the poet’s ekphrastic compositions. The project will involve the creation of a series of audio, video, and textual content inspired by the collection, which will be distributed through the Museum’s channels. These materials will also be part of readings designed to engage the public and encourage different ways of interacting with the artworks.

The project is part of a series of live readings arising out of Tinti’s image worship; he has been composing poems inspired by works of art for many years. This series has been presented in some of the world’s major museums, including, among others, the J. Paul Getty Museum and LACMA in Los Angeles, and the British Museum in London.

G: We first met in 2020 right here in Rome, at Palazzo Altemps, remember? For Shelly, Rome is ‘at once the Paradise, the grave, the city, and the wilderness‘…

A: Rome, a paradise? Rome is a paradise in hell.

They both laugh.

G: For me, Rome is the space where I find what I seek the most. Everything is here, layer after layer… it’s not even necessary to dig, just to walk through these spaces. For example, behind your house there is this church, the Basilica of SS. Sylvester and Martin, which I’m not sure if you know because there are a hundred churches in your neighbourhood…

A: Yeah, I know it well, I’ve been there several times.

G: So, you’ll recall that by descending just a few steps, you find yourself right inside a Roman villa. The weight of time is incredible here… After being wide-open mouth of eternal words, the hard stone where everything has It is the remained, ruin, fragment where nothing is lost. It’s the center of the world in ancient times, Rome still remains, for me—and not just for me—important for these reasons: its incredible density and depth, and its role as the heart of Christianity, the most followed religion in the world. Don’t you think Rome still holds great significance in some way?

A: It’s one of the world’s capitals. Everyone is based here. The CIA, the KGB, the Mossad. It’s a crucial spot between East and West. But if you’re talking about spirituality, the real spiritual center of the West is Jerusalem. That’s where Christ lived and died. Here in Rome, his followers, starting with Peter and Paul, were killed and are now venerated. But Rome existed long before all of that. Trust me, there are more atheists here than anywhere else in the world. The Vatican is a state within another state, with its own laws, its own economy, and its own problems. There isn’t much spiritual about any of this. If you walk into the many churches, you won’t find them as places where people genuinely come to pray. They’re full of tourists taking selfies with the artwork in the background. I don’t see widespread devotion, a real community in that sense. They’re no longer something living and breathing.

G: But they’re still testimonies of a past that you can feel in the air, a past that has defined us…

A: The world has changed though. From my house —you know where I live, near Piazza Vittorio— if I take a short walk, it’s as if I’m in Bangladesh. I walk one block, and it’s like being in a Chinese city. I turn the corner to head home, and suddenly it’s as if I’m on Park Avenue, where everything seems fine and everyone looks happy. That’s the center of Rome today.

G: Rome is also the space where pagan and Christian presences, their simulacra, coexist.

A: It’s everywhere. Sculptures of ancient gods sit side by side with Christian paintings in some museums. Pagan temples, on whose ruins churches were built. This reflects ways of thinking and seeing the world that have survived to this day and continue to influence us.

G: My poetry is the result of a Christian education that derives from the agonistic spirit of the Greeks and Romans and considers existence as a battle on foreign land (Marcus Aurelius), our body and mind as a battlefield of forces that transcend us and will finish us. It does not entertain, it does not console, but it aims to be a signal to stay alert and to try to understand the violent and brutal part of the world, exorcising it. It is an attempt at prayer, lament, confession. When I was a child, my family forced me to be an altar boy, and as I recall, you told me some time ago that you were one too….

A: No, actually, I was never an altar boy. I would have liked to be, but I couldn’t. It was my dream….

G: …it was my nightmare instead.

They both laugh.

G: I spent my childhood at school with nuns, like you. An education that led me astray, at least for a period of my life…

A: That kind of upbringing stays with you. The hymns, the rosary, the litanies, the rituals, the incense. My father went to church because he was convinced he was a sinner. They had made him believe that by going there, he could cleanse himself, and if he didn’t go, he’d end up in hell. My view of Christianity comes through Buddhism. After all, Jesus was basically preaching a form of Buddhism.

G: For the early evangelists and Christians, there was a strong need to escape the material traps of this life, the readiness for martyrdom, to dissolve themselves and identify with the ‘body of God’ through the imitatio Christi. The anonymous 14th-century writer of the Actus had Francis say: ‘I have no greater enemy than my own body”. The sense of not fully belonging to this earth and to one’s body is an ancient issue. The body was considered, both by the ancient world and by the Christian world, as a protector but also as a prison of the soul, as an impediment, obstacle to contemplation as a device of passions and needs, a place of expiation of sins. A vision then further carried out by Christianity, for which bodily death will be an essential consolation and the day of death, dies natalis. I do not believe there is an afterlife but that we are earth, Pulvis et umbra sumus, we are but dust and shadow as Horace wrote. Dust that will nourish new creatures. The problem for Christians is accepting the end of individuality, which is instead, if I am not mistaken, part of Buddhism…

A: Yes, that’s right. Christianity believes in the dualism of body and soul. But where is the soul? Can you see it with an X-ray? Where is this thing we call the soul? The first Buddhist teaching is this: we have a car. Imagine a car. Take away its wheels. Is it still a car? If you remove the bumper, what is it? If you take out the engine, is it still a car? What makes a car a car? What makes you, you? That car is only our collective perception of what it is. You can’t say ‘this is my soul,’ whether it’s in my mind, my heart, or somewhere else… we exist in the relationship that constantly shifts the scene. This person I believe to be Abel, who I know what he wears, what he thinks, how he reacts… that person doesn’t exist. He’s constantly changing. Being open in this sense means being free…

G: Because we are the result of our past, the relationships we’ve had, the encounters that have marked us, the people we have been…

A: You can’t step into the same river twice because you’ve changed just as the river has changed. That’s the beauty of being in the world. We’re not at all imprisoned by our minds or our so- called soul as we might think. We can breathe and change.

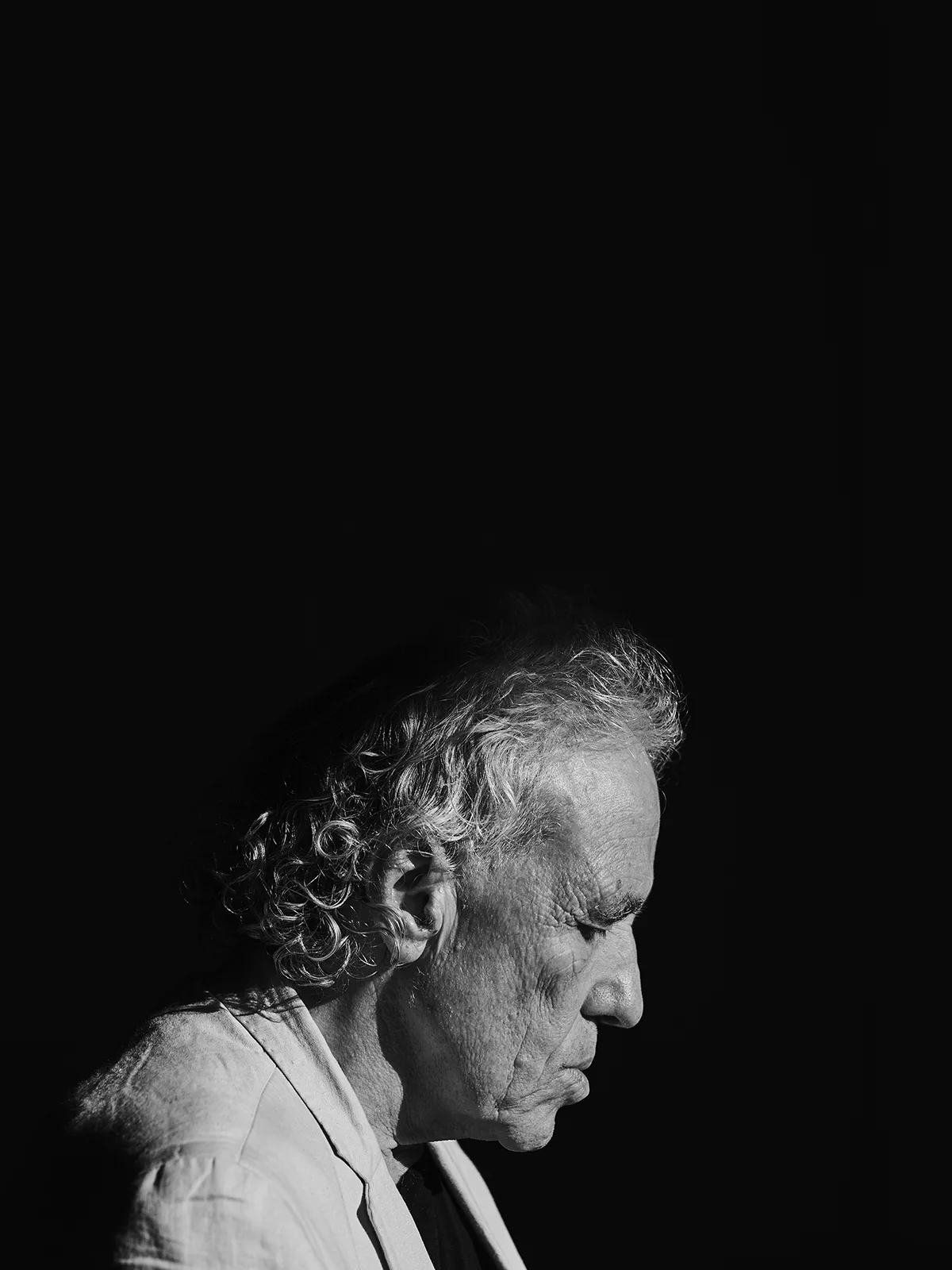

G: But the body can be an obstacle. I remember never feeling well. When I was a kid, I had ear infections, adenoid issues, allergies of all kinds. Every time I went out to play, I’d come back home with a fever or a sore throat. My childhood went by like that, stuck at home reading. Then adolescence was spent with heroin as an attempt to heal and finally feel good. I don’t remember a day when I felt in harmony on this earth…

A: …not even when you were using?

G: Yes, when I was using, yes!

A: That was the cure!

G: Yes, the illusion of a cure.

A: Illness itself is an illusion.

G: I believe art, in general, feeds on these kinds of fractures between the self and the world. If we are already in harmony, resolved, it becomes difficult to create something…

A: I’ve spent my life thinking that way. I’ve come to realize that I need to be clear-headed, focused. Creativity is both inside and outside of you.

G: I like to view our series of readings as a theater of memory, a phantasmagoria that lets the ghosts, the remains, the fragments that still lie among the ruins, speak. Because I’m convinced that beauty resides in what remains, in something that has been and that we can no longer fully recognize, but still desire. We are the result of our past, always drinking from the same source, which is our thirst for transcendence and expansion…

A: Exactly: you write your poems to expand yourself, to express yourself. And that’s why we read them in public; when I read your poems, sometimes I repeat certain lines. At that moment, the meaning of the line changes, it becomes something else. And if I read it again, it takes on yet another meaning. In that instant, the only reality is me speaking your words. We don’t know how much the audience gets all this, but who cares? What matters is that it matters to us and that they come to listen. There’s a thirst for expression, to push our respective limits, the willingness to use our words. It’s something true. Something alive. Time disappears, and the ancient images, the ancient myths, begin to speak again.