Gazelle Mba speaks with Acaye Kerunen on the occasion of her solo exhibition Neena, aan uthii at Pace Gallery, where woven sculptures and tapestries connect art, domesticity, and Ugandan identity. Her work reveals the poetry in quotidian objects and the artistry within natural materials.

There are no straight lines. Hung on the gallery’s stark white walls are multi-coloured woven tapestries that curl and snake, crimped strands falling over themselves. In the spaces between these works are stand-alone sculptures. Some are small and placed on bright yellow plinths, resembling domestic objects – pots and jugs – that I imagine passed around kitchen tables by young, sticky hands. One is called Ott Ker (House of Reign), a concise work of woven raffia. As the artist notes, ‘it is compact, it is tight, it is delicate. A universe unto itself.’ Alongside these minor universes are larger ones, more amorphous in shape. They dangle from the ceiling like thick swirls of cotton candy or clouds, full and exuberant, an embarrassment of riches. In a certain slant of light, they appear almost to be floating – reminding me, joyfully, of the Mark Doty verse:

The jellyfish

float in the bay shallows

like schools of clouds,

a dozen identical — is it right

to call them creatures,

these elaborate sacks

of nothing? All they seem

is shape, and shifting,

I see the exhibition more clearly through the prism of his words. The shape and shifting before me is Acaye Kerunen’s Neena, aan uthii at Pace Gallery. An exaltation of tangle and curve, surfaces rippling like streams of fresh water.

Neena, aan uthii, as the artist tells me, is an Alur phrase for ‘See Me, I am here taking up space, claiming space, standing in my light, finding my line and my race, running it and winning.’ Her voice exudes a hushed reverence, a pride that radiates between each word. She speaks to me from her home in Kampala, Uganda, which she shares with her two young sons, and although the signal leaves much to be desired – but despite abrupt pauses and infuriating static, our conversation persists. She continues, ‘Neena, aan uthii is for the little girl within that could never have fully imagined all this, she is pinching herself saying we made it, we reached one of the summits of the mountains and now onto the next. So, see me or perceive me, I am here, I am present.’

Neena, aan uthii is the artist’s first solo exhibition in the UK and I feel this lively confidence carries through in the sculptures on display. They ‘take up space’ unabashedly. Look at me, notice me, they say, all vying for your attention with their extravagant colours and textures. And yet, the twisting, convoluted shapes combine to form a singular object, one made of many parts but still whole and complete, a universe unto itself. ‘To be here’, these sculptures insist, is to delight in complexity.

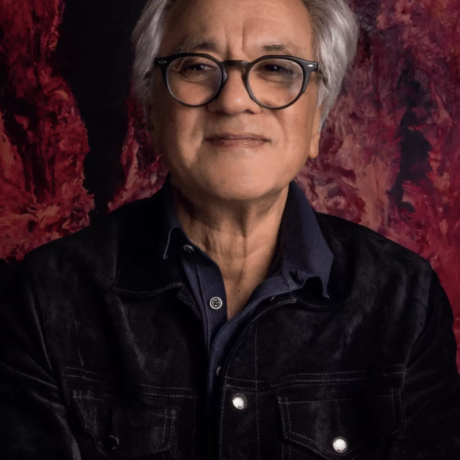

Kerunen’s artistic practice is as multifaceted as her sculptures. She is a writer, editor, curator, poet, actress, and performance and installation artist. She has assumed many roles within the art world, learning to exceed the limitations imposed on African artists by the force of her ingenuity and willpower. Her work has been exhibited and performed not only in her native country; she was the first female Ugandan artist to exhibit under the first ever Ugandan pavilion at the 59th International Art Venice Biennale. She has also shown her work at group exhibitions, including Ars Belga in Brussels and the Barbican Centre in London. Kerunen’s biography is not tangential to her art; Neena, aan uthii is formed by the conditions of the artist’s life. In some ways, it is a document of those conditions, a vessel through which she imparts on the world some of what it means to be a woman, a mother, and an African artist ‘making it’ in the international art world.

Kerunen did not receive a conventional art education; she learned to be an artist from watching her mother. While at high school, she was shamed out of drawing class as her sketches were considered too ‘abstract’ but at home her penchant for abstraction would meet her mother’s practical tutelage, a woman who spent a portion of her days fixing roofs and sewing garments. From an early age, Kerunen made her own dolls with banana fibre and rags, wove textiles and mended clothes. These practical skills mixed with her poetic sensibilities have led to the works we see as part of Neena, aan uthii. The materials of her childhood: banana fibre, raffia, palm leaves are dolls no longer, but sculptures draped elegantly from gallery ceilings. Here ordinary, domestic objects take on a deeper significance – as though these sculptures are not made for the benefit of the art world, but to revere the hearth and home, which the artist holds sacred.

Neena, aan uthii suggests that art is not separate from homemaking but integral to it. It takes a certain kind of magic to make a lot from a little. Artists do this, as do mothers and caretakers around the world. The relationship between motherhood and artmaking informs Kerunen’s art. Motherhood is both a practical matter and a philosophy, an act of nurturing and a form of pedagogy; it involves, above all, the passing down of knowledge from one generation to the next. But in this context, the mother is not confined to teaching her children survival skills, she teaches them how to live which is just another way of saying how to make art.

Kerunen tells me that Neena, aan uthii was created in the pauses between caring for her young sons. She describes the ‘rhythm’ of her life as a stay-at-home mother as one she falls into ‘naturally.’ She makes time for play, for cooking, for working. The respite between these different life-sustaining activities feed into each other; leisure in a busy and striving city like Kampala inspires what she calls ‘the work.’ A term that I start to see as blurred and all-encompassing. Work is play, work is leisure, work is childcare, work is art. Her practice reminds me of Diane de Prima’s poem ‘Imagination,’ particularly the lines:

there is no part of yourself you can separate out

saying, this is memory, this is sensation

this is the work I care about, this is how I

make a living

it is whole, it is a whole, it always was whole

In Kerunen’s work, the spiralling, biomorphic shapes – the tapestries that break out beyond the two dimensional plane into our space, the curves and soft shapes – are attempts to visually articulate this wholeness, this unity of self and surroundings. The how and why of her practice are intertwined. Just as her sculptures are constituted of spiralling layers of natural materials, their making is similarly intricate, engaging artisans from across Uganda’s sixty-five primary communities. Working collaboratively, the artisans and Kerunen source materials such as palm leaves, sorghum and millet stems, sisal, raffia palm, grass, banana fiber, and bark cloth. They strip, dye, braid, weave, tan, and crochet these materials. Every aspect of her process is fluid and regenerative, fitting into her life as a mother rather than working against it.

Kerunen’s preparation for the Pace show was built up over two years, beginning in October 2022. Over that period, she continued making, setting aside materials, deconstructing and rebuilding while juggling other artistic projects and commissions as well as raising her young children. Neena, aan uthii’s construction was slow and iterative; and it is precisely this unhurried pace that delivers a show so striking in its materiality and attention to detail. Composed, as it is, of woven tapestries and sculptures that resemble complex equations, it demands patient attention.

For her, the weaving of these sculptures presented a series of mathematical equations to be solved simultaneously with each weave following its own logic. The weaver, she tells me, approaches their structure as a numerical problem solved only through weaving. Sometimes, the completed work reveals this; at other times, this fact is concealed. It occurs to me then that as weaving obscures its mathematics, the domestic often hides its own artistry. Women who clean, sew and cook have often had their art denied or overlooked. Offering an alternative, Neena, aan uthii softly argues that to make life, is also to make art. It’s quiet message resounding with these words from Doireann Ní Ghríofa:

This is a female text, composed by folding someone else’s clothes.

My mind holds it close, and it grows, tender and slow,

while my hands perform innumerable chores.

Neena, aan uthii is a female show, whose ornate sculptures and tapestries were woven between putting her sons to sleep and caring for her home. These sculptures are not mere art objects but traces of an ongoing, living practice. Through her work, Kerunen insists that art, labour, and life can never be separate. It is a whole, it is a whole, it always was a whole.

Written by Gazelle Mba