Amadou Sanogo paints on cloth scraps and textiles he finds at a fabric market in Bamako. The market not only provides his material, but his palette and ambience. The local market in his hometown, Ségou, has particularly influenced his art.

In Sanogo’s Eclairerur, 2017, a headless, seated and naked feminine figure balances a barbell, a boxing glove enclosing one hand (the other is truncated) and a sports shoe on one foot. The painting possesses its own mysterious pictorial code—like a visual riddle. It currently hangs in the imperial surroundings of Casa Cadaval, a former royal residence in the small, southern Portuguese town of Evora, where a three-month-long celebration of African culture is taking place from until 25 August.

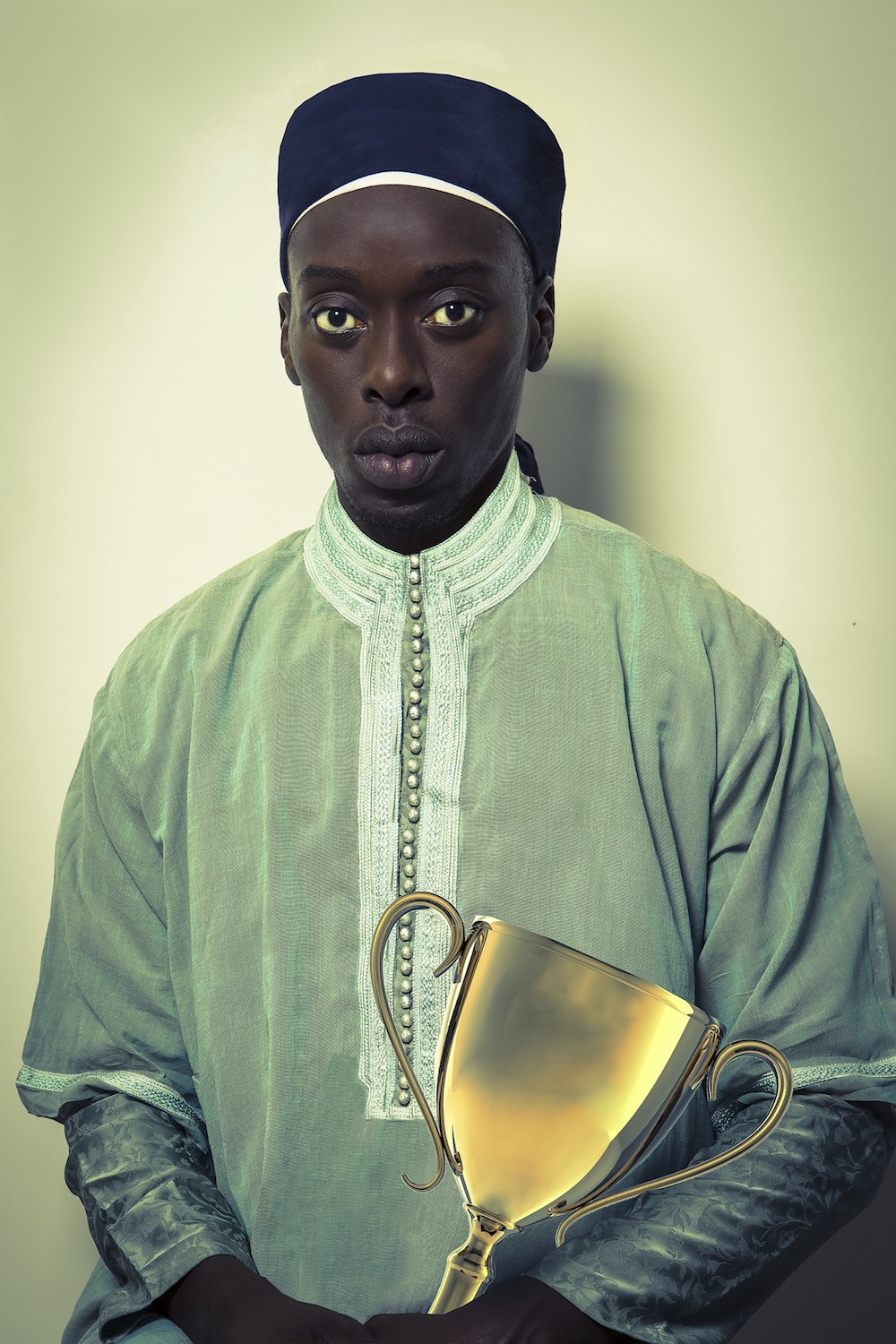

African Passions includes sixteen artists from two generations and different countries, curated by André Magnin—who began working with African artists in Europe the 1980s—and his long-term colleague Philippe Boutté. Their mission is to introduce the inventiveness of African artists to the local Portuguese audience—who seldom see contemporary arts from the continent. “We didn’t aim for completeness but the desire to show the diversity, vitality and dynamism of African artists,” Magnin tells me. “They are not ‘exotic’ artists but contemporary creators, resolutely African but open to the world, without denying their own history and culture,” he adds.

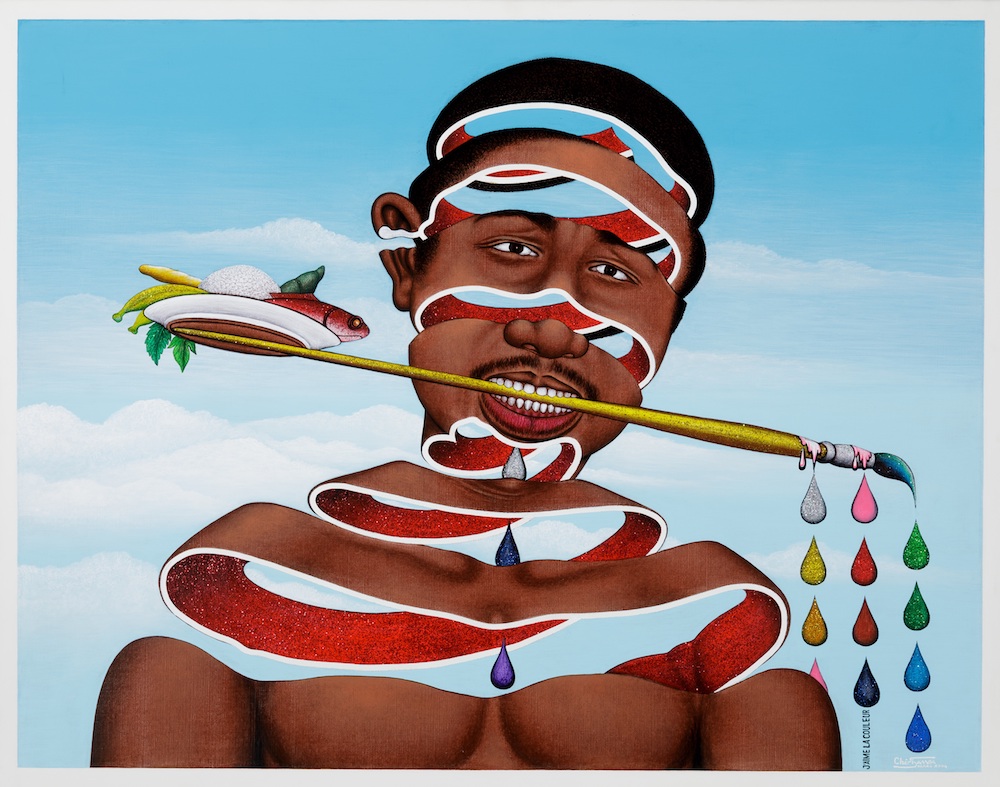

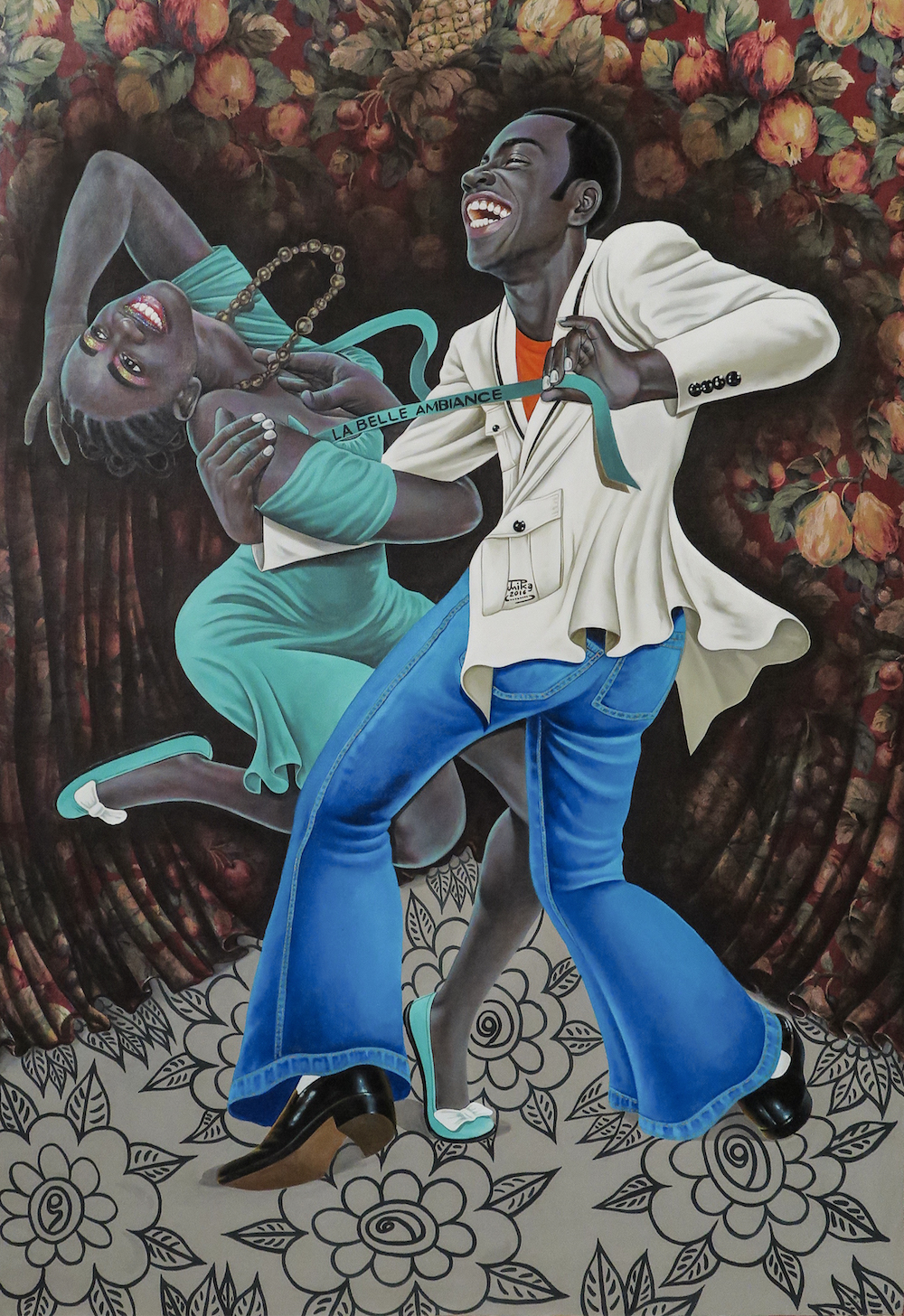

- Chéri Samba, J'aime la couleur, 2004

- Chéri Samba, Bouquets de Fleurs au 3eme Age, 2016

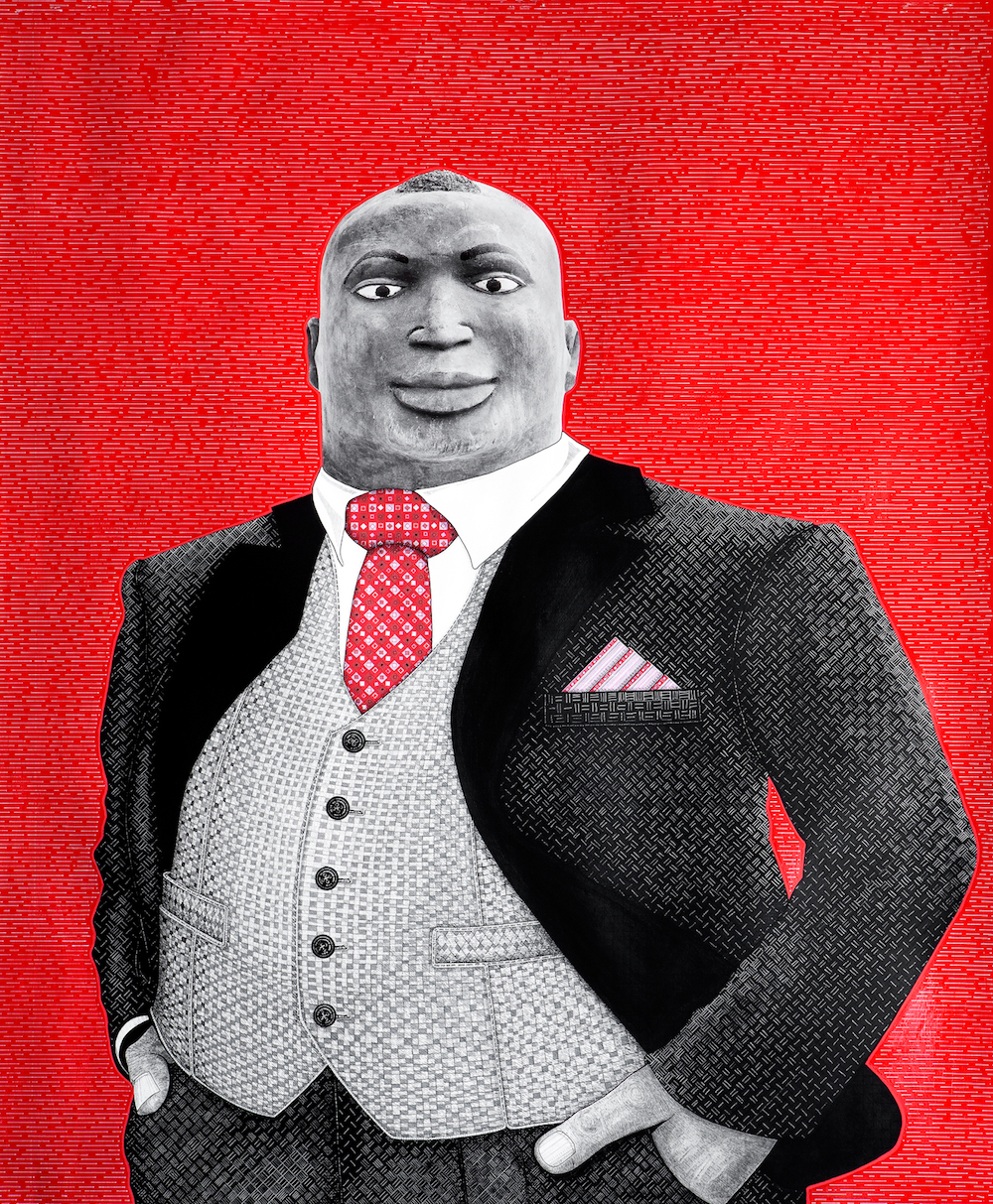

The exhibition presents compelling individual stories such as those in Sanogo’s works, but is tempered to the “unaccustomed” viewer, those familiar with the more established artists of the western art world. One intriguing exercise of the exhibition, for instance, is to compare works made by artists who were born in colonized countries and witnessed independence, and those born in independent countries—and who also grew up with the internet. There are more photographs of local rituals and customs by young Mozambican artist Mauro Pinto, and upcoming Johannesburg-based Phumzile Khanyile’s more intimate, diaristic female gaze.

“The exhibition presents compelling individual stories… but it is tempered to the ‘unaccustomed’ viewer, those familiar with the more established artists of in the western art world”

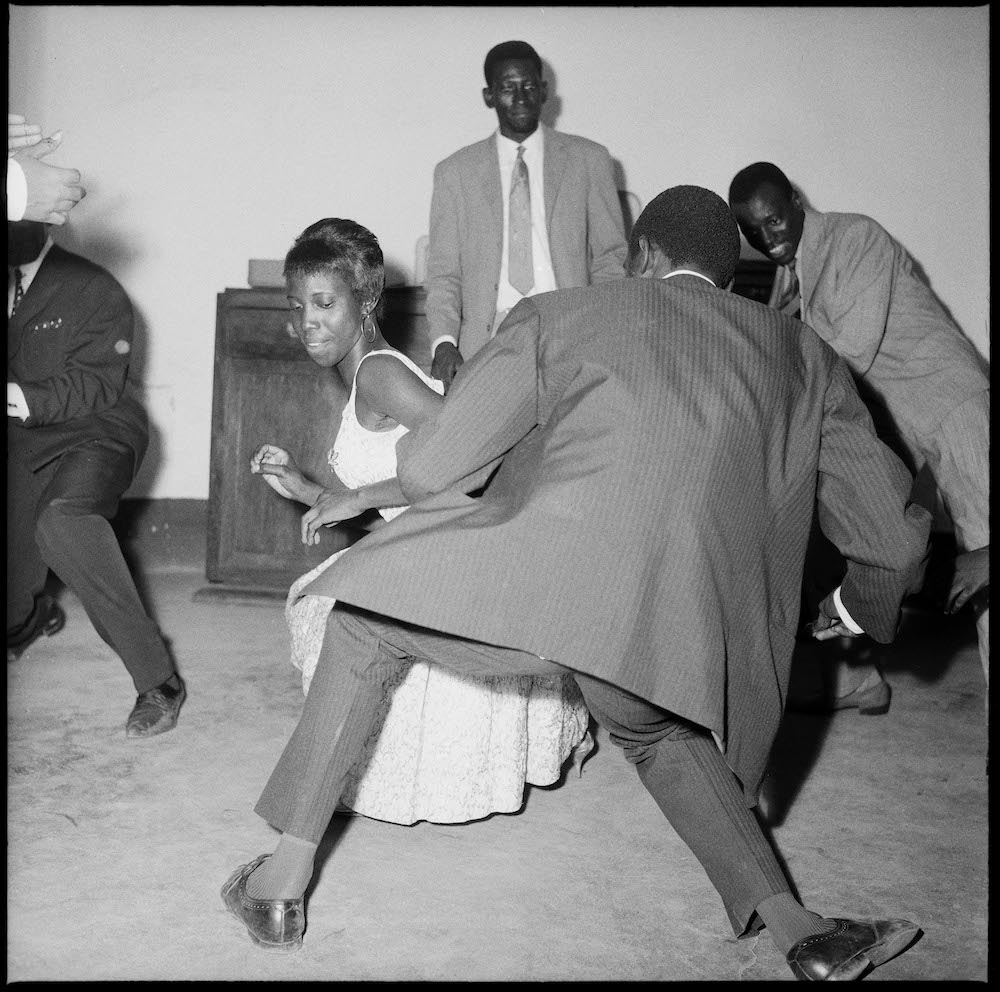

Pinto and Khanyile’s consciously-cool photographs have a distinct atmosphere from Sidibé’s iconic portraits of early independent Mali, necessary, vivid documents that are more directly celebratory and less ambivalent. Equally, Chéri Samba’s famous figurative paintings of Congolese people used punchy humour to deliver messages about political corruption, sexual and economic inequality, at a time when daily life in Kinshasa was dangerous. Both in their style and purpose, these have little in common with Sanogo’s more mysterious paintings, for example—made in a different time, landscape and with their own heritage and history.

The exhibition inevitably prods at the visibility of African artists in the west, and contemplates ways of seeing. Magnin points out that, in the same week African Passions opens, MoMA will present a solo exhibition by Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez in New York. Kingelez will be the first African artist to ever have a solo exhibition at the MoMA. “It was not until 2018, but it finally happened,” shares Magnin.

But there is also something dichotomous in demand of so-called “international” success in the art world—meaning, the approval of a few institutes in major cities in the US and Europe—just as there is an unresolved question in presenting exhibitions of “African” art or “women artists”. There’s no doubt we need to keep challenging what we mean by “international” and “global”, and the structures according to which we evaluate and define art. In recent years, with fairs such as 1-54, now with outposts in London, New York, and Marrakech; as well as “West Africa’s first international art fair”, Art X in Lagos, and Johannesburg and Cape Town’s own commercial fairs, the infrastructures have started to shift, particularly as more museums and foundations are investing in young African artists than ever. “All of this gives a greater visibility and better recognition, even if much remains to be done in the west, as well as in Africa.”

“There’s no doubt we need to keep challenging what we mean by “international” and “global”, and the structures according to which we evaluate and define art”

As for Magnin and Boutté, “we have never asked ourselves the question of legitimacy of presenting and defending artists from African countries.” They say. “But does someone have to be German to be interested in the work of Gerhard Richter, American to appreciate Andy Warhol or Belgian to approve of the paintings of Magritte? Of course not, and it is high time, as Iba Ndiaye Diadji wrote, to recognize ‘the possibility of learning to learn from others.’”

In the Unesco-protected scenery of Evora—in a country that until the 1950s was a colonial force in Africa—and in an exhibition curated by two Frenchmen, this presentation of contemporary African art is nonetheless mediated by the western eye. But in light of all the different perspectives it touches on, the exhibition in Evora unfurls an interesting proposition.

In Billie Zangewa’s patchwork silk embroidery, Christmas at the Ritz (2006), there is also a narrative, buried but less obfuscated (with text references to the Ritz, Issey Miyake and Swatch). The artist grew up between Malawi and Botswana, later moving to Johannesburg. The pieces that make up these comic strip-like patchworks seem to assemble all the fragments of Zangewa’s life—with her experience as a woman at the centre of them. They are sunken stories, only be partially retold. The landscape and surroundings that inspire Zangewa are remote from those of Evora, but this difference isn’t the reason we look at them, and it doesn’t affect how we look at them. Art is beyond geography, history and bodies. African Passions builds bridges to contemporary Africa in Evora, but—just like the works of Zangewa and Sanogo—it tells an open-ended story.

All images courtesy galerie Magnin-A, Paris