Kirsty O’Rouke, Ally Hart posing for Fat Life Drawing

Life drawing is one of the most accessible gateways into the world of art and design. It has classical origins yet is opportune for marketisation; intimate but rarely uncomfortable; enjoyable for the novice while still taxing for the expert. Both modelling and drawing can suit all manner of personality types and creative desires. It is also an invitation to a wider world of artistic practice; the live model offers a safety net for realists and an invitation for abstraction.

Like many activities, the adaptability of life drawing has been tested over lockdown—a period which, for many people, has distilled the true value of their hobbies and work. So why do people opt for life drawing? The enjoyment of the process itself is one reason; its social or community element is the other. For most, it is normally some combination of the two, often with a third factor thrown in, such as therapy or academic training.

When classes moved online as lockdown was introduced in the UK in March, the relationship between these dimensions changed dramatically. The human architecture of the exercise was converted to pixel form: bodies were flattened onto small screens; sketching in isolation became the norm. In-person classes are now steadily returning. What can they learn from the world of Zoom?

Lifeclass Live with Stuart Semple

From the beginning of the lockdown, drawing has played a prominent role in broadcasters’ project of pastoral care for the nation, scaling up the “alone together” mentality for the quarantined millions. In late April, the first episode of Grayson’s Art Club (led by Turner Prize winning artist Grayson Perry) on Channel 4 focused on portraiture; one of the first segments shows the artist making miniature pencil sketches of his wife Philippa in under two minutes.

The BBC’s Life Drawing Live! (initially a one-off programme in early February) returned in mid-May, using a streamed online “Pose Cam” for participants across the nation. The site also featured video clips from artist Nicky Philipps, who guided viewers through difficult technical elements of drawing (hands, face, proportion and shadow) with only a slight air of superiority. During the live broadcast from the Pop Factory in South Wales, artist Lachlan Goudie played the role of gameshow judge. As they cast a critical eye over the socially distanced easels, the programme evoked the seemingly inexhaustible tradition of every last British pastime being made competitive—cooking, baking, sewing and now finally, inevitably, life drawing.

“It’s not the same as being in a studio, it is different, not worse, just different”

Online classes have largely reflected the range of pre-lockdown sessions. The Drawing School at the Royal West of England Academy has moved their tutor-led classes online, retaining an academic approach to developing observational skills. Their Introduction to Life Drawing class will resume in person at the end of July, though most sessions will have fewer than five participants, who will be escorted through the building before taking their positions. Dulwich Art School have been streaming their short pose classes at a cost of £5 an hour. “It’s not the same as being in a studio, it is different, not worse, just different,” says its website, candidly. The haste to reinstate live classes suggests that organisers feel a keen yearning for the old ways.

Some groups have decided to strip their sessions back further in order to financially support life models who have lost income during the lockdown. Tottenham Art Classes run non-live life drawing: models submit photographs before the video-stream begins, with participants working from still images. It’s a significant departure from the fundamentals of the practice, but speaks to an increased emphasis on drawing’s community value—and the “something-is-better-than-nothing” ethos of the past months.

View this post on Instagram

In many cases, live-streamed classes have led to a surge in participation, engendering alternative forms of community: less intimate and personable, but more global and diverse. Before the pandemic hit, artist Stuart Semple ran small life drawing workshops from his Dorset studio. In choosing Facebook over Zoom for his digital transformation, he was able to stream to over 3,500 people at one time. “We went live to different models’ homes from all over the world and brought them into people’s living rooms to draw,” Semple explains. “It’s a way to encourage people to start making. It definitely is a gateway in deeper practice, but that’s not to belittle drawing as a starting point. It’s a discipline in itself.” Participants ranged from university students collectively logging on to replace their art school sessions, to people drawing for the first time and then uploading the results to Instagram using the hashtag #SempleLifeClassLive.

For others, the community element of life drawing classes relies on their more ritualistic, therapeutic elements, which are difficult to emulate online. Sarah Garnham, a charity sector worker in her twenties, began attending sessions at the end of 2019 after relocating to Thamesmead (she had previously tried out a class at Dulwich Art School, but found it “very intense”). Choosing life drawing mainly for its social potential, she built friendships not only with fellow participants but also the cast of rotating models—often contortionists, performers or dancers—who would stay behind to chat with drawers after the session.

“What’s missing over Zoom are the small discussions in-between poses”

“What’s missing over Zoom are the small discussions in-between poses, because either we weren’t really talking very much, or there were too many people,” Garnham says. A lack of proficiency with recording equipment and space restrictions also mean that models would sometimes lie on their beds, making it difficult for novice artists to capture their forms. The basic technical drawbacks are obvious: images are shrunk onto laptop screens, making depth and lighting inconsistent and tricky to judge. Everyone is also drawing from the same angle, replacing the characteristic half or full circle of a studio.

Although it is challenging to exchange ideas and feedback, there is a certain safety and reassurance in logging on from a domestic setting—especially when lockdown restrictions were at their tightest. The whole process becomes less onerous and intimidating; the accessibility benefits for disabled and time-constrained participants are abundant.

“We’re not artists or art teachers; w online pharmacy inderal no prescription pharmacy e’re facilitating a safe space for people to create art without judgement buy robaxin online robaxin online generic “

Noticing the uniformity of body types on show in online classes—and the often intimidating atmosphere of academic-led groups—sisters Emily and Isobel Cameron created Fat Life Drawing in March this year. The Zoom sessions platform fat, queer, non-binary, BIPOC and disabled models, who each select a charity for participant donations (tipping the models is also encouraged). A strong community and thriving Instagram page quickly followed. “We’re not artists or art teachers,” explains Emily, distancing the project from more austere, instructive environments. Like Semple’s classes, Fat Life Drawing’s Spotify playlists play a big part in creating a relaxed atmosphere. “We’re facilitating a safe space for people to create art without judgement or a focus on proportion or formal technique,” she says.

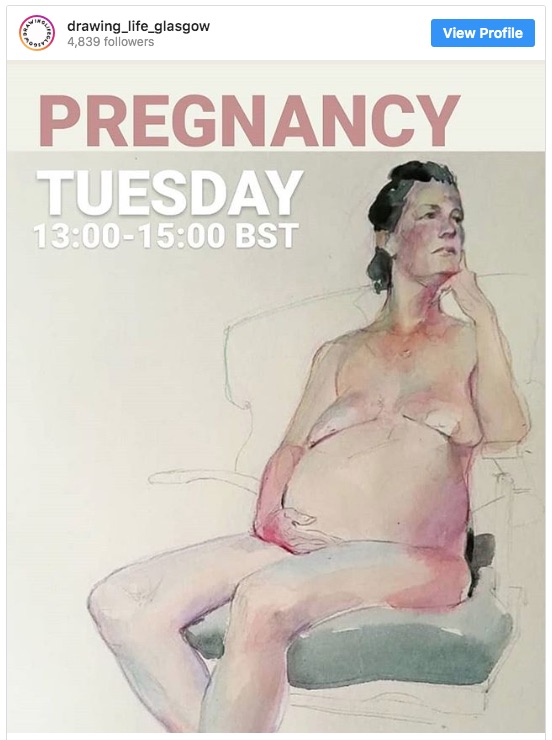

The sisters don’t view the classes explicitly political, rather an inherent celebration of overlooked and underrepresented body types. Diversity is a cornerstone of the project, and they are in no rush to return to in-person classes which can narrow participation, often along socioeconomic lines. “The internet isn’t always a safe space for people with fat or queer bodies,” Emily explains. Safeguarding has been paramount as their brand has grown. The move online has also provided a more protected environment for others like Natasha, who has worked as a life model throughout her pregnancy. Last week, she sat (in the virtual realm) for Drawing Life Glasgow at seven months pregnant. In terms of comfort, accessibility and diversity, models often benefit from the shift to digital as much as the artists.

For Semple, moving his classes online has prompted more questions about his practice than it has answered. “The idea of the internet as a space in which we can share experience is just beginning,” he reflects. “I don’t think we’ve really seen the true explosion of proper communality online and in public spaces.” His expectation going forward is that digital streaming will work in tandem with in-person classes—a trend that is likely to extend across the participatory arts. It is a convincing solution, and one that upholds the accessibility and diversity benefits of newly online classes, while also resuming the face-to-face community that connects the scene. Like much of the creative sector post-lockdown, hybridity is an attractive response to disruption.