Alec Soth needs little introduction. Over the last twenty years he has established himself as a key creative voice, documenting America in all its grand and banal beauty. His photographs reveal a curious, roving eye; the artist casts his gaze on everything, from the close up of an ice-packed cocktail in a seedy bar somewhere outside of Niagara Falls to a hermit’s caravan in a forest. Often his series feel, not only like they could have been taken almost anywhere in America, but like they could be from any time period at all. This curious sense of timelessness has long lingered in Soth’s work, and his large-scale projects are frequently cited in the lineage of great American photographers that includes Walker Evans, Robert Frank and Stephen Shore.

Soth’s latest project takes a decidedly different route. “After the publication of my last book about social life in America, Songbook, and a retrospective of my four, large-scale American projects, Gathered Leaves, I went through a long period of rethinking my creative process. For over a year I stopped travelling and photographing people. I barely took any pictures at all,” he wrote upon the release of his new body of work this March, titled I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating—named after a line in Wallace Stevens’s poem The Gray Room. “When I returned to photography, I wanted to strip the medium down to its primary elements. Rather than trying to make some sort of epic narrative about America, I wanted to simply spend time looking at other people and, hopefully, briefly glimpse their interior life.”

“When I returned to photography, I wanted to strip the medium down to its primary elements”

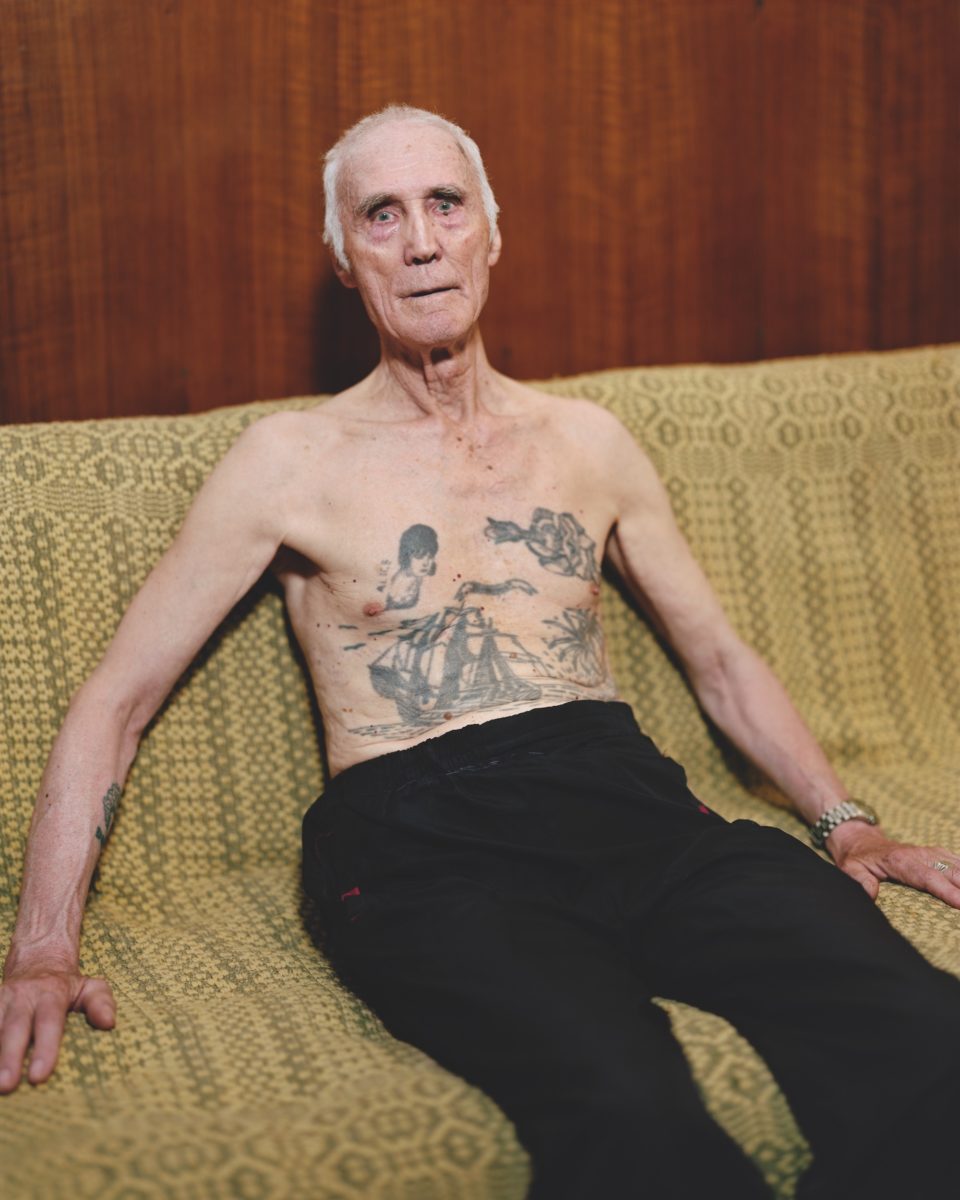

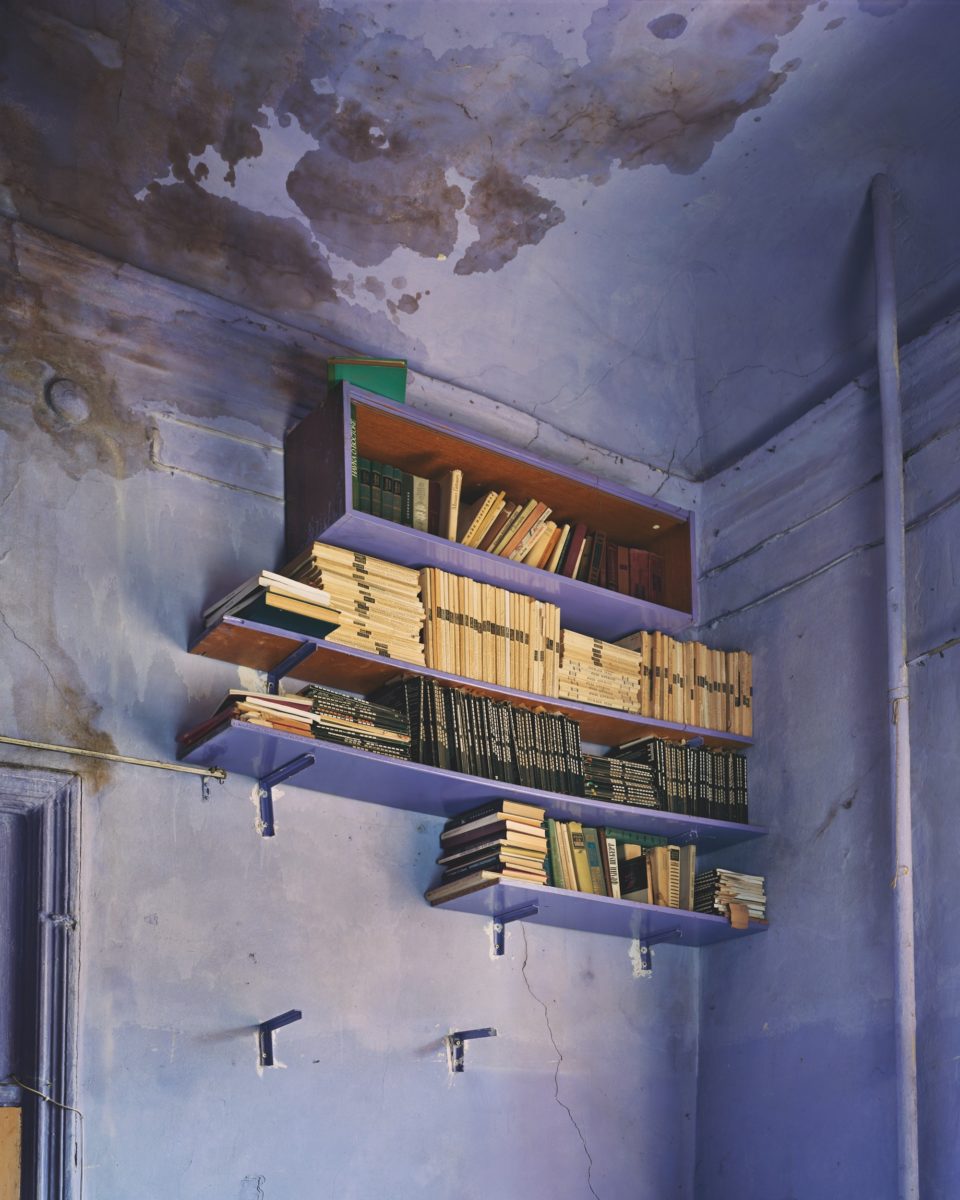

The result is a work of quiet beauty, situating Soth himself at its heart as the connecting force between this diverse group of creatively-minded people. The collection of portraits brought together in his latest book (published by Mack) were, for the most part, taken in their subjects’ homes. Still life shots of some of these interiors accompany the portraits, revealing details of lives that are otherwise unknown. As a whole, they expand upon notions of interiority; of the spaces that we inhabit both inside and outside of our own mind. These are images that are deeply intimate, caught in a moment of reflection.

The garments and accessories that we each use to build (or shield) our identity come into focus throughout Soth’s images. In one, a man stands looking out of the window in nothing but his underpants; a collection of blonde and brunette wigs lie tangled on the floor beside him. They hint at a persona beyond that who we see in front of us, and at a life lived beyond normative rules and expectations around gender and self-presentation. This is a common thread woven between the photographs. In another image, a man lies in the foetal position on a plain white bed, tenderly clutching a few sprigs of dried flowers; he is vulnerable and exposed, a far cry from the male posturing often seen in society.

Others lie languidly lost in thought, or occasionally sit looking straight back at the lens. Soth’s own presence can be strongly felt in their stare, unravelling the uniquely intimate interaction between subject and photographer. This sensation is heightened by the framing of some shots from a distance, through curtains or bookshelves, as if we were peering in from a hiding place. Rather than create the discomfort of the voyeur, we are given a feeling of privilege, of access to private moments rarely witnessed. One particularly personal photograph reveals a woman looking at herself in her dressing table mirror, alongside a series of photographs taken at various stages of her life; in these images, she is glamorously coiffed and staged, while in Soth’s own photograph she is absorbed in her own present-day reflection. She glances at herself, and back out at the camera once more; the act of looking itself is fully felt.

“Rather than create the discomfort of the voyeur, we are given a feeling of privilege, of access to private moments rarely witnessed”

Soth’s subjects are named only at the end of the book, and even then only referred to by their first name, leaving their presence in the images themselves largely unknown. The only other context we are given is the city that each photograph was taken in, tracing a private map of America and Europe. The chronology of the book is ambiguous, moving between people and places in a series of visual connections that feel intuitive and emotional.

I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating raises questions around where we feel most at home, and where we find ourselves truly at ease. For many, this is a space where they can be alone with their own thoughts, free from the pressure to perform for others. The majority of Soth’s subjects are photographed in solitude, some with their eyes closed or looking down. Their gaze is fixed on a point that we can’t access, but through the act of looking at them we are able to share—even momentarily—this time and place with them. In images that are as revelatory as they are enigmatic, Soth offers peace and quiet enough to sense the soft rhythm of the heartbeat that gives the series its name.

All images courtesy MACK Books

Alec Soth, I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating

Published by MACK Books, out now

VISIT WEBSITE