All images courtesy the artist and Josh Lilley Gallery

Bad Land at Josh Lilley Gallery marks Da Corte’s first, large-scale solo presentation in the UK. It is the third exhibition in a trilogy initiated in 2013, in which the artist embodies the persona of Eminem. Walking into the exhibition feels like entering a stage set or cartoon storyboard. The show spans four galleries, orchestrated to unfold sequentially like a film narrative as the spectator moves through the environment. The first space—on street level—is bathed in a lurid, yellow light with a vertiginous, green and pink tessellated floor. The psychological effect of colour and its relationship to the anticipation of emotion is important to the artist, who has been inspired by filmmakers like Fassbinder and Dario Argento.

“I want the first room you experience to be the leading colour for tone and mood,” he explains when I visit during the install period. “I started thinking about things that are famously yellow and what they connote. Yellow hair, crowns—both your head as a crown and a yellow-gold crown—the Midas touch, the yellow brick road, SpongeBob, and the idea that yellow typically prompts or equals fear.” Da Corte has built a smiling, yellow, box-shaped cartoon hairdresser—which is hung in the gallery window—complete with neon legs and arms brandishing scissors. Downstairs, there is large, glowing, imperial green and gold crown, flourished with ruby gems.

The adjoining galleries downstairs are saturated in hues of pink, lavender, green and yellow through gelled neon lights. The carpet is thick and soft. The film, Bad Land, depicts Da Corte in the guise of Eminem as Slim Shady. Although three films are screened separately in three spaces, he sees the work “as one video with three chapters, with the upstairs space being the prologue or the trailer.” Da Corte wanted to explore the psychology of being in the home and performing a simple task. “It’s akin to Bas Jan Ader doing a task or Bruce Nauman doing a task,” he says, “except I’m asking ‘what is Eminem doing in his house, alone, with no one watching?’ In one, he is untangling the wires of a bunch of PlayStation controllers. In another, he is smoking weed out of homemade bongs. In the third, he is making a sandwich with white bread and yellow mustard.”

These bongs are exhibited in the gallery as an independent work, The Whale, and made from a variety of plastic objects characteristic to Da Corte’s installation practice: washing detergent bottles, shampoo containers, an oversized tennis ball, an orange Nike trainer, soft drink cans, plastic fruit, vegetables and toys. Placing these bongs outside of the video instates the fact that these objects have a history; they are part of a broader aesthetic language and a wider world. It also returns to the concept of the installation as a rolling narrative; everything is experienced within the context of time.

The environment is familiar yet strange, somehow both artificial and authentic. All visual associations are deliberately open and evocative, as opposed to prescriptive or didactic. “The language of all the work is meant to guide you, but not tell you anything,” clarifies Da Corte. The exhibition is analogous to a dream space. “I’ve taken away all signs of the real world. No outlets, no electrical power,” he continues. “Often when you wake from a dream things weren’t as you expected, you weren’t as you would be or what you wanted was reversed. We don’t get to do that in waking life. I don’t want you to walk into a weird place à la Alice in Wonderland—that’s too easy—but I’m trying to resist what your expectation is of certain things.”

Bad Shoe—a supersized white Adidas Superstar trainer—is also installed downstairs. The tongue is separate from the unlaced shoe, lent up against the wall. The relationship between power, class and taste can be easily read through sartorial culture. “My work has always dealt with the collision of class and taste, insofar as where taste represents something you want but something you don’t have,” he explains. “It reveals something about yourself and where you’re from.” What masks do we use in order to perform our identity? What is someone trying to represent—consciously or subconsciously—by purchasing and wearing these particular trainers, and by keeping them so white and so clean? Similarly, Da Corte perceives the Slim Shady character as a mask for Eminem. “He plays himself up—baggy white shirts, big blue jeans, his hair is bleached so yellow he almost looks like a Ken doll. I think he was interested in homogeneity and sameness. What power does that produce?”

It’s an empathetic project, too. “Adopting a persona has given me a better understanding of difference. Marshall Mathers adopted this character Slim Shady, and I’m only adopting that character. Can you actually adopt another persona that is not yourself, beyond just changing your clothes? I think our President has.” Is this exhibition a way for Da Corte to respond to the political situation in America? “Artists are called to be transgressors and survey their land. It’s no coincidence that my recent show in Vienna [Slow Graffiti]—the first show after his election—was trying to think about ways to speak that were softer. Here I’m exploring another way, speaking with rage and anger and shade.”

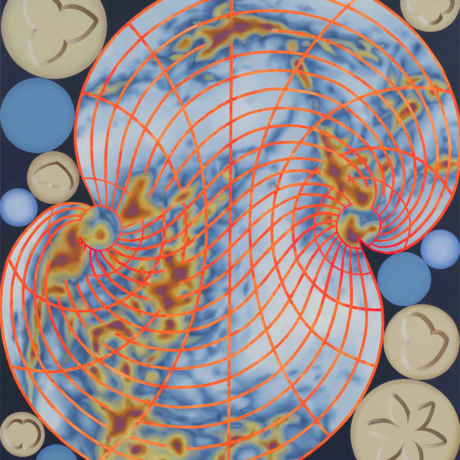

In addition to six acrylic diptychs titled The Gossips, the walls of the exhibition are commanded by eight large-scale, colourful multimedia works, which utilize commercial Slatwall or vinyl siding. In Bad Breeze, Bad Break, Bad Cross, and Bad Cage, Da Corte creates variant impressions of a house window, some broken or barred. In The Breather, Garlic Tip (after Bronzino’s Allegory of Love), White Storm, and Haymaker, he combines idiosyncratic objects with cut-out standees (Elvira Mistress of the Dark, Dracula, a Star Wars Storm Trooper and The Wicked Witch of the West, respectively).

“As cliché it may sound to reference The Wizard of Oz, which is such a crazy film and still beautiful after so many years, I want to try and empathize with bad or mean characters as misunderstood,” he says. “Slim Shady was misunderstood. The Wicked Witch is misunderstood. A house just landed on her sister, she’s pissed, understandably!” The concept of being misunderstood, or what produces this perception of “bad”, is also a nod to the area of Philadelphia that Da Corte lives in, known as the Badlands, “What makes a bad land and what makes a bad man? Can a bad man wear a good shoe? Can a good man wear a dirty shoe?” There is a latent power in the vernacular of slang; to have the ability to own the meaning of a word, so that “bad” can become “good”, or “shady” can become “funny”.

Slim Shady was Eminem’s controversial and sadistic alter ego. “He amplified this voice of an underprivileged, middle class, white man, but celebrated violence and misogyny. The original message of his work, what my initial project centred on, is very problematic. My question was always trying to understand why that message was celebrated,” considers Da Corte. “It is anti my own ethics. I didn’t want to celebrate something anti-woman, anti-gay. Where was he really coming from?” Last month, Eminem released a four-minute freestyle video publically lambasting Trump, criticising his racism, white supremacy and lack of gun control. Da Corte finds it “cosmically strange” that Eminem is simultaneously having this moment. “It’s interesting to see him revisit his original project with a new voice,” he continued. “This desire to speak at all comes from a lack of voice, or an imbalance of power. If you have no power, in order to be heard, you have to shout, and be the most bad and the most mean. Once you have the power to make change, you don’t have to be screaming all the time.”