Of all the artists whose work it’s delightfully easy to look at, Alex Katz is right up there. He’s been making work since the 1950s, and continues to do so at ninety-one. With such a vast and varied oeuvre, it’s easy as viewers to hone in just on what the artist has made, and sidestep the art that in one way or another helped him make it. And while the old “What inspires you?” question is a tired and cliched line of enquiry, it’s always fascinating to really understand the works that an artist with as much standing as Katz draws on, and what they mean to them on a truly personal level.

A new book from Laurence King Publishing does just that: Looking at Art with Alex Katz is described by the publisher as like a “private museum tour” through art history, led by Katz himself. Delineating Katz’s personal responses to, and encounters with, more than ninety artists, it offers a succinct and compelling overview of the pieces that have most touched the artist throughout his career right from the horse’s (or artist’s) mouth.

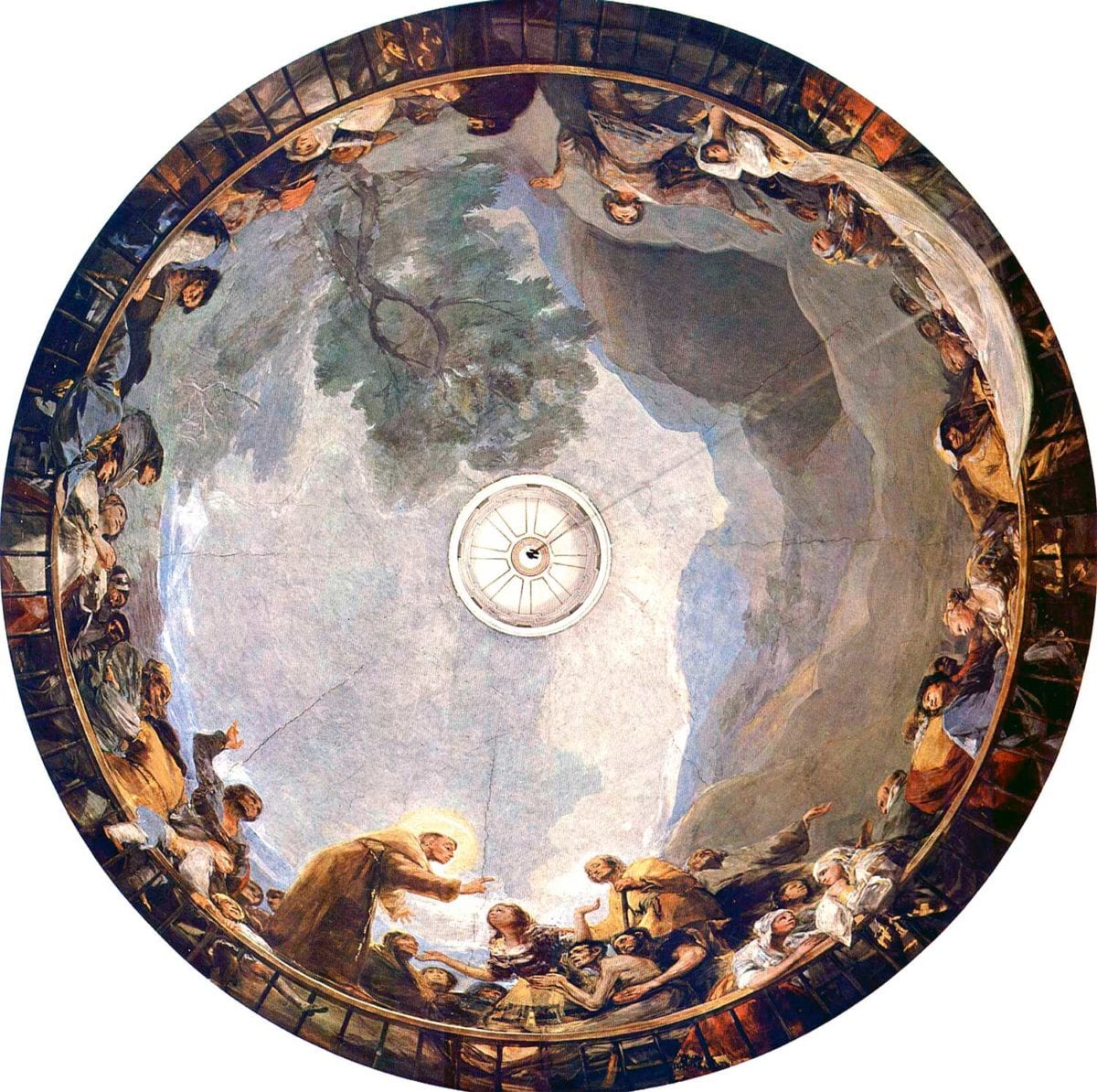

- Left: Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Red Hat, c.1665. Courtesy Andrew W. Mellon Collection. Centre: Cezanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire, c. 1902 - 1906. Courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Right: Goya, The Royal Chapel of Saint Anthony of La Florida frescoes, c.1798. Wikimedia Commons

Katz’s own graphic, luminescent and modern approach belies many of the sources he describes as being most dear to him. “In high school, I was supposed to study advertising, but I came across beautiful antique drawings, and I spent most of my time drawing from antique casts,” writes Katz in the introduction. Realizing he could “learn something,” the young Katz would spend an entire week on one antique drawing, “involving two to three hours a day of intense looking.”

Following his stint at what he describes as “modern art school” Cooper Union in New York, Katz went on to a “regional art school” in Maine, the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and it was there that he began painting more quickly, outside, and where “the manner of painting actually became my subject matter”, he writes. Those landscape works drew him to become a disciple of Picasso and Matisse, and how they “described forms in paint”, as well as the way Bonnard and Pollock “spread light” in their work.

As such, those four all feature in the book, alongside less starry guides he’s looked to on the way. It’s fascinating to see the way poets informed Katz’s work: he discusses New York School original John Ashbury, as well as visual artist and poet Joe Brainard in the book, a later addition to the tight-knit, gossip-laden world of the New York school of artists and poets that emerged in the 1950s. In Ashbery’s work, Katz writes of his admiration for the “cool, fluid” style of his poems, which “move from image to image, thought to thought, without any loss of his large energy line”. His description of Brainard almost mimics the writer’s own conversational, vernacular style, and Katz describes his seminal 1970 poem book I Remember (quite rightly, in our eyes) as being “as good as it gets”. Katz says, “Joe added so much for all of us. I miss Joe.”

”There is no progress in art, only change”

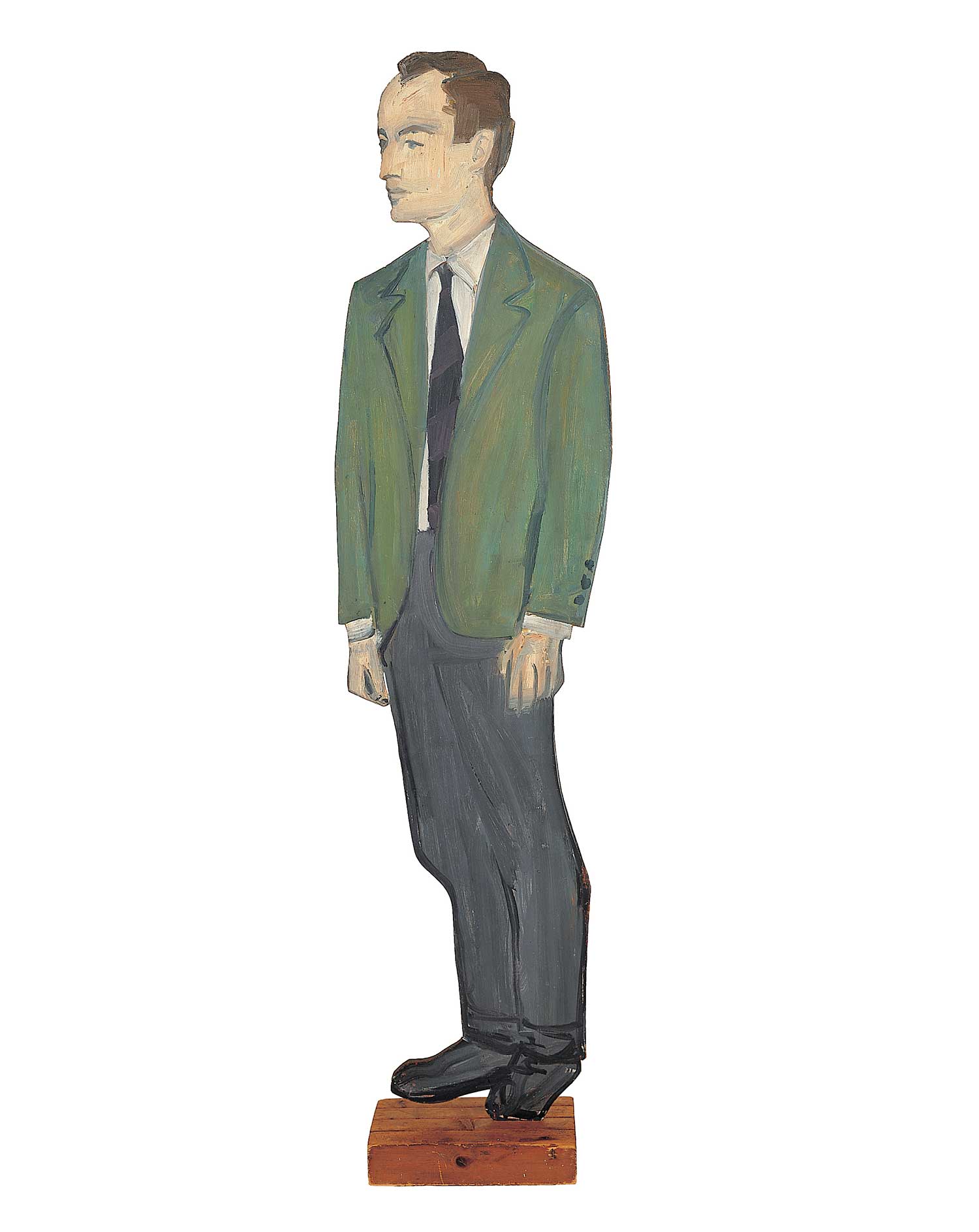

The New York School looms large throughout the book, with Katz also discussing painter and poet Ted Berrigan and his “emotionally open” sonnets. Often, Katz links such works to wider cultural movements, such as jazz, and the societal milieu that underpins them. “Berrigan’s [use of dope] is public and proletarian,” writes Katz. “It’s the vernacular language of our time. This is a tremendous achievement.” As for other featured NYS-stalwarts—poets Kenneth Koch and Frank O’Hara—Katz’s descriptions offer a sense of deep understanding and appreciation of the intermingling of visual arts and text that created the group; as well as his intense friendships within it. He admires Koch’s “manic, sad optimism and his violent passion”—all of which are poignantly visible in Katz’s 1970 portrait of the poet. Similarly for Frank O’Hara, perhaps the most famous of the New York School poets, Katz writes of his “optimism about being alive… He makes the period he lived in vivid… I think he extended himself further emotionally than his friends. I would love to be able to make an art with these qualities.” Katz’s own woodcut portrait of the poet hints that his own emotional reach, and vivid realizations, perhaps aren’t as far off as he modestly describes them.

The book beautifully mixes such personal recollections and musings with Katz’s broader reflections on art history, and his notions of what makes a great painting. In his introduction, Katz discusses the idea of “manners” in art: Warhol, he says, “has great manners in painting. He’s always interesting, and he’s never coarse.” He also distills what makes any work timelessly great; stating that any work that has “style” when it was made will always retain that.

Katz concludes: “Art doesn’t progress, it just changes, like fashion in clothes or music. There is no progress in art, only change.”