Ali Banisadr and Huma Bhabha Examine their Creative Practices as Restorative World-Building Exercises

Despite the apparent differences between their work—one is primarily a painter and the other a sculptor—artists Ali Banisadr and Huma Bhabha have recently formed a profound friendship. Having met earlier in 2023, the two artists have since hosted one another for studio visits and collectively uncovered the uncanny similarities between their practices: they both draw extensively on artefacts from ancient civilisations, deploy techniques of assemblage and collage, grapple with their diasporic experiences and identities and seek to examine the present as a product of the past and a warning for the future.

As migrants living in the United States, who have both carved out prestigious careers in their own right, Banisadr and Bhabha create almost futuristic works by harnessing the stories that have shaped their pasts. Having both grown up amongst ruins—Banisadr endured the realities of the eight-year Iran-Iraq war, while Bhabha was greatly affected by urban decay in Pakistan—they are both charged with a passion for the preservation of ancient transglobal artistic histories, and have an acute awareness of the ramifications of current events and a desire to reconstruct notions of belonging, family and home through their artistic practices.

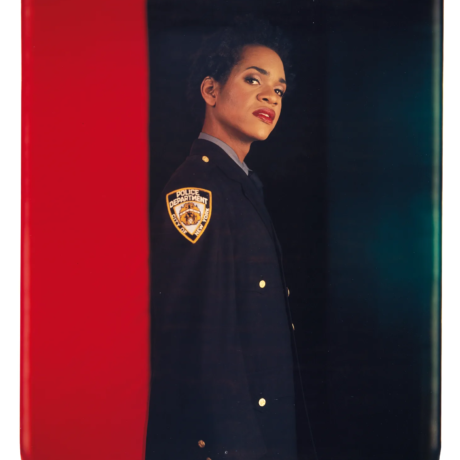

An internationally acclaimed sculptor, Huma Bhabha garnered significant attention in 2018 when she produced We Come in Peace, two colossal bronze figurative sculptures for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s roof garden. Born in 1962 in Karachi, Pakistan, the artist moved to the United States in 1981 to attend the Rhode Island School of Design, followed by the School of the Arts at Columbia University, New York. During her studies, she discovered a passion for assemblages and began creating the three-dimensional works that would come to define her career. Now in her 60s and based in Poughkeepsie, Bhabha is represented by David Zwirner Gallery in London, David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles and Xavier Hufkens in Brussels, and is currently presenting her first institutional show in Belgium at M Leuven. This exhibition follows her first major survey in Europe at the BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art in 2020. Her work has been exhibited extensively, including at the Sydney Biennale in 2020, the ICA Boston in 2019, the Venice Biennale in 2015, MoMA PS1 in 2012 and the Whitney Biennial in 2010.

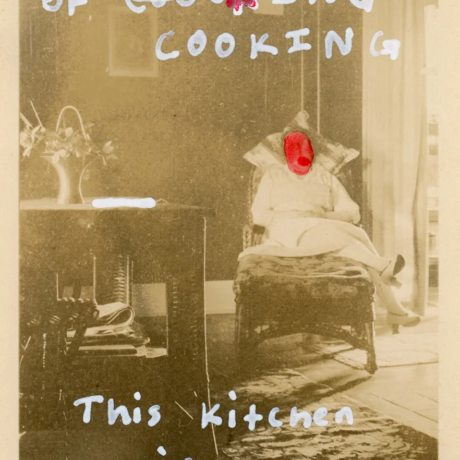

Bhabha is known primarily for her sculptural pieces centred around the figure as a recognisable yet abstract, otherworldly and emotionally communicative form. She creates monumental, haunting and androgynous, human-like creatures that tower menacingly over the viewer, often formed from unlikely assemblages of salvaged materials including fragments of furniture, industrial polystyrene boxes, alongside clay, wood, cork, paper, plastic, rubber and metal. These bodies and busts appear as both relics of a historical ruin and products of a far-flung future fallen back into our time. Her pieces’ unique ability to traverse time by simultaneously gesturing towards the past, present and future, is born from Bhabha’s capacity to synthesise an incredibly diverse range of influences; her practice is rooted in the past through memories of her home city of Karachi and her fascination with the artwork of early civilisations, alongside the present through her perceptions of current events, her love of twentieth-century modernists like Giacometti and Picasso and her enduring interest in science fiction and the visual lexicon of horror films.

With sculpture at its centre, Bhabha’s practice also extends to collage, drawing, photography, painting and printmaking, a diversity of media that further allow her to dissect an age-old subject of artistic inquiry, the human figure. Often alien-like and deeply affecting, her rough and intense two-dimensional pieces create a universe of their own. Across her diverse oeuvre, allusions to war, migrant experience, colonisation and ecological fragility reside within and ricochet between her pieces in various forms. Their sense of timelessness positions the artist as an almost omnipotent entity, able to transcend time and reveal a panoramic view of humanity’s complex histories, the chaos of the present and the possibilities of the future.

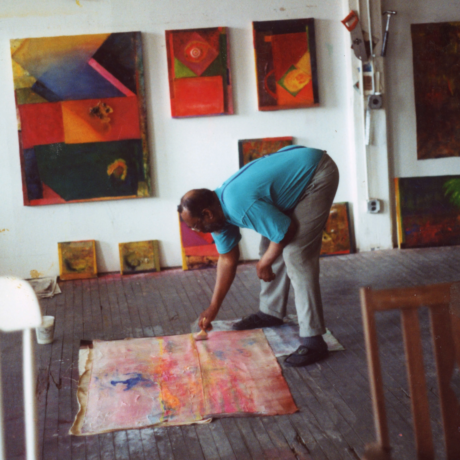

Ali Banisadr, a contemporary painter born in Tehran in 1976, is similarly interested in incarnating bold narratives that speak to the essential nature of human existence. His gargantuan, epic and entrancing canvases depict turbulent worlds inhabited by enigmatic figures and imbued with a wide range of reappropriated symbols from art history, deployed as poignant reflections on the tumult of our time. Like Bhabha, research is central to Banisadr’s creative approach, with recurring references including the exquisite detail of Persian miniatures, the power of gesture in Abstract Expressionism, the hidden narratives of early Dutch masters, the bravura technique of the Venetian Renaissance and the libidinous forces at play in Surrealism.

Currently based in Brooklyn, Banisadr has been represented by Victoria Miro since 2021 and will present his first solo show with the gallery in October 2023, titled The Changing Past. This phrase goes a long way to summarising the aims of the artist’s work: by incarnating a hugely multifarious range of painterly languages drawn from art history, Banisadr is able to speak openly and powerfully on the ambivalences and absurdities that have shaped his lived experiences. Turning his attention to the recent dismantling of monuments in the name of the Black Lives Matter Movement, for example, the artist retraces histories of colonialism and the legacies of past incidents of iconoclasm to create works that literally reframe and recast history in a new light.

His upcoming exhibition with Victoria Miro builds on the artist’s 2021 solo institutional exhibitions at the Museo Bardini and the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, Italy, and previous solo shows with Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut, and at the Benaki Museum in Athens, Greece, alongside his inclusion in institutional group exhibitions at The Opelvillen Foundation in Rüsselsheim, Germany, the V&A in London, UK, and the Orlando Museum of Art in Florida.

Having both described the figures within their works as a self-made family, Ali Banisadr and Huma Bhabha bravely, and with penetrating clarity, utilise their artistic practices as world-building techniques to create a sense of belonging. Still in the early days of their blossoming friendship, the artists sat down to discuss the inspiration behind the figures in their works, the impact of war and instability on their trajectories as artists, the power and importance of remembering and how they might make art that can stand the test of time.

Huma Bhabha: Having recently visited your studio, I wanted to ask you about the figures in your work. Are they a product of organic inspiration, like accidents of the paint, or are they premeditated forms you insert into the work?

Ali Banisadr: I spend a lot of time looking at visual imagery from many different times and places: paintings from the Renaissance, illuminated manuscripts from the Mediaeval period, Persian miniatures. I internalise them and then they re-emerge organically during the painting process.

At the beginning, my paintings are very abstract and fragmented, and then as the process continues, I start to see possibilities in the paint. Living things emerge within the fragments— certain characters, figures or archetypes keep recurring in different forms. As it develops, the piece itself will recall certain images and prompt me to go back and find the type of figures I’m already seeing in the paint. In essence, my process is a combination of internalising numerous images, seeking them out deliberately, and them appearing organically in the work.

How about you? How does it work in your practice? I’m sure you also internalise a lot of images, and then when you make your work, does it prompt you to go and look at certain images again?

HB: For me, it’s a continuous process; I find myself looking for the kinds of images I’m interested in everywhere, all the time. I’ve noticed there are threads that run through the choices I make in terms of what I want to look at. Certain artists or styles seem to recur, so when I’m making a work, I might have a printout or a book nearby that will then inform the piece I’m creating.

But it’s not always clear to me initially what a work is connected to. I might be looking at something new, and then I’ll notice as I work that the piece is influenced by it in some way—it might be hidden in a detail. There’s a natural feedback loop between myself, the work and the things I’ve been looking at. As a sculptor, the tools and my ability to use them also dictate the final form, so the works will change as I discover new methods or materials.

AB: Even though my sources are so varied and disperate in terms of genre, I often feel like patterns emerge between them. I find connections between a film I’ve seen, a book I’ve read, a certain kind of imagery I’ve been looking at and something that’s going on in our time. The figures end up representing all these things at once.

HB: When I visited your studio, I noticed that there’s usually one dominant colour that takes your focus. How do you decide if a certain work is going to be a certain tone?

AB: To begin the paintings, I use a self-made base colour: there’s a handful of them by now, and they all embody different moods. The decision as to which to use is predicated on the mood I want the painting to incarnate, which itself is often informed by the painting I’ve just finished.

But, during the process, the atmosphere of the work might change entirely. Once I begin working into it, I’m stepping into an unknown territory—it goes from a white canvas to a total sort of chaos in one day. That’s the exciting part: the piece becomes a challenge in front of me and I have to try to solve the problems within it. The communication begins between me and the painting as I attempt to see within the fragmentations and create a harmony within the chaos.

HB: So, your figures are coming out of the chaos.

AB: Yes, exactly. I remember seeing a book about HR Geiger in your studio.

HB: I’m fascinated by his early drawings for the Alien films. I continue to watch those films over and over. I like all his works very much, but the Alien pieces are absolutely exceptional.

AB: The first art book I ever purchased was on HR Geiger. I was just so fascinated by the power of his sculpture. There’s an ancient quality to the things he made: they’re akin to something you might see in ancient Near Eastern or Egyptian artefacts. We’re both fascinated by things from that time. They encapsulate the essence of culture, as the products of the first civilisation whose creativity we have a record of. In my research, even when looking into a current topic, I somehow always end up back there.

HB: It’s the cradle of civilisation, and its fragments have been strangely preserved by later cultures. In some ways, it’s miraculous that they still exist, given the histories of conflict in certain parts of the world.

Ever since you mentioned that story about your school being bombed and subsequently being adjacent to a bomb crater, I’ve wanted to ask you about it. Do you think you’ve come to understand that very traumatic moment and has it unconsciously emerged in your work somehow?

AB: I don’t think I’ve understood it, no … It’s something I’m still grappling with. When you experience a place where bombs are being dropped as a child, you begin to question humanity. Why would humans do this? How could they do this? I became somewhat skeptical of humans in general as a result.

On the other hand, the visual impact of it—which was too grand for my brain to understand at the time—has been influential for me. I grew up seeing ruins, incidents where a building was whole one day and in half the next. I remember seeing a bombed house, and there was still wallpaper and children’s toys inside. I could see them because one side of it had crumbled down. Half there, half not there.

People describe my work as abstract figurative, but in my mind the compositions really come from that place. It’s not about abstract figurative, it’s more about seeing things that are partly there and partly not there. I wonder about how to put a fragmented world back together. Maybe that’s something I thought about as a child that has stayed with me—how do you preserve something? Perhaps that’s why I’m interested in so many fragments within our history and culture; I want to understand them all, to see connections between them, and ultimately to put them all back together again.

In terms of the crater in the schoolyard: I remember playing next to it with the other children. I think it showed up more clearly in some of my earlier works and it probably still exists within my practice now, but in a different form. And you were saying that when you visited Pakistan, you also noticed certain aspects of ruin there and that this has impacted your work in some way.

HB: Yes, but the ruin is very different there. I haven’t experienced direct conflict in the same way as you have—or only once when I was a kid, when there was a very short war; it lasted for about four or six days. I guess I’ve experienced a little bit of it, but nothing compared to what you went through. As a result, I can’t understand it fully. I can only try and imagine it. But the ruin I did see made me aware of how the world is ageing, and how a lot of that is created by conflict, corruption or just mismanagement—cities fall apart.

Especially where I’m from. I’ve been going there all my life, and recently I began to examine why I like the city where I’m from so much. And it’s because—despite the dry, desert, arid climate, ugly construction, garbage and constant chaos—it contains so many beautiful moments that really resonate with me.

I think my experience of its landscape has affected the surfaces of my sculptures. As I made the works, I started to understand the city more. I think this also relates to works by Anselm Kiefer and my interest in Arte Povera and Land art—the urban ruin.

When I thought about the ways in which wars are constantly ongoing, on some level or another, and how this affects an area and its capacity to grow, I started to see decay everywhere. I think that’s why the experience you had really stayed with me. You experienced it physically, which must be a whole other kind of trauma—it’s like a vibration that can stay in your body forever.

AB: I hardly know anyone of my generation who has experienced that kind of thing. I can relate to, let’s say, the surrealists, because war was happening during their time, but I hardly know any other artists of my generation who have lived through such a horrific war for such a long time. I don’t have examples of other artists similar to me whose work is affected by war, or the psychology of it.

HB: Yes, how it sort of releases itself through the work.

AB: Exactly. This also makes me think about how we make our work, in particular using assemblage, collage, or combined fragments. We both work with plural images. I wonder if that has to do with wanting to first understand the world, and second to assemble the world back together. I tend to like worldbuilding in art or literature and I was just thinking that perhaps it has something to do with the fact I’ve left my home and I’m trying to put things back together.

My work makes me feel safe, it feels like home. Maybe it’s all about trying to build a home in this world. Do you think about that? Does that resonate with you?

HB: Yes, that makes a lot of sense. I haven’t previously thought about collage that way, but maybe I do unconsciously.

I was initially a two-dimensional artist: I made drawings, paintings and watercolours, but I remember realising that I enjoyed using different materials when I started adding things to the surface. It was really exciting to me; bringing together two materials that weren’t supposed to be together felt so natural. At the time, I was a sophomore and I was looking at a lot of assemblage work, and I suddenly became really inspired by it. I just let it happen and it didn’t matter if it didn’t make sense, or if it wasn’t what I was supposed to be doing.

I think in some of my works the idea of assemblage is prominent, especially when it’s of two figures joined, or some kind of architectural structure. I don’t know if I think about it as home, but I do think of my sculptures as my family.

AB: I feel like the figures that I create are my family and it makes me feel safe. I also feel like using assemblage, collage or fragmented painting as a way to take different languages that don’t intrinsically make sense together, and to somehow make sense out of them all. They end up being one structure or one painting, but within that, there are many voices, which is a true reflection of identity because we’re complex and made up of multiple parts. It’s a way to make sense of yourself, and again, maybe to preserve something of yourself too; to put into one place all the things you’ve picked up from different places.

HB: A tapestry of the self in some way … In your work, the figures often contain references to ancient cultures. What elements in your work are completely new, coming from the present or even the future?

AB: The painting from which my upcoming show’s title is drawn, The Changing Past, was initially inspired by the recent dismantling of monuments. It was so strong to me as an image at the time and it reminded me of so many historical moments of iconoclasm.

There are also elements of something I’ve recently become fascinated with—the Rebis figure, a hybrid form that has the head of a man and a woman contained within one body. My recent small paintings explore notions of being genderless. Another very large painting, Numinous, depicts an entire ceremony, a marriage of sorts, and there’s also this idea of the union of a male and female figure presided over by an ancient priest.

Within each painting there are all these different elements, combinations of things that have caught my attention. Some of these elements exist within our time, some are historical and art-historical references that I’ve sought out as a result, and then there are thoughts about my personal history as well.

New elements that have recently come into the work are geometric or architectural forms. I feel like they function as the algorithm of the painting. These forms didn’t really exist in my work before. In some of my earlier works, say from 2008, there was something similar but it went away for a while. Now, it’s come back in a different way, which I’m kind of excited about.

HB: They almost look like wormholes. It’s as if they’re routes through the painting, traversing the spaces between the figures. In your large-scale blue work, the pink architectural lines seem to be creating passageways, allowing the figures to almost move around on the canvas.

AB: With that piece, I was also thinking about what might happen if an AI or some kind of disruptive digital force entered the painting. I think the whole painting functions as a disruption. Those architectural, portal lines give that sense of interruption. It’s also about thinking of ways to break up the space so that it’s not like a landscape, but more theatrical, like a stage.

HB: I love the painterly techniques that you use, your ways of creating certain effects with the brushwork. Obviously that’s important to you—figuring out different ways of making marks.

AB: Every day that I come in, I want infinite variety. Every day, I feel different and that makes me want to go about tackling the painting in a different way. I find all these different ways of solving the same problem. I look at the work and think about how another artist might solve the problem—how do I solve this from the headspace of Tintoretto or Hiroshige? Every day that I come in—even within the same day—my approach keeps changing, the mark-making keeps changing and the routes through the painting that I see change too.That’s why I have a table covered with different books, so I can find the reference that the painting calls for. The books are routes to remembering something, reminding myself of a work so I can get into a different headspace. I guess it’s just a form of memory.

What role does memory play in your work—and by “memory” I don’t just mean personal memory; it could be collective memory, or ancestral memory. There’s this quote from Orhan Pamuk, “To know is to remember that you’ve seen. To see is to know without remembering.” It suggests to me that we’re always trying to remember what we already know. Rather than filling one’s memory with experiences, it’s more that everything is already contained within our collective ancestral memory and we’re merely shining a light on it. Or as Henri Bergson would say, we have antennae that catch the frequency of consciousness or memory. And then, as artists, we tap into and then materialise it. Do you think that’s true? Do you think about that for your work?

HB: For me, it’s about trying to be in the moment as much as I can. I try to work where there’s little distraction, so that I can put everything into concentrating on the work. I’m interested in being aware of my surroundings; it helps me to see the present and the past. I think about how things are happening. Sometimes I feel like it’s not a very pleasant forecast, but I carry on. As an artist I take on the idea of bearing witness, which involves being aware and outside of just my own world. I have to be able to connect to the external.

AB: I always see it that way too. Sometimes it’s as if I’m observing humanity through the eyes of an alien, watching human behaviour, human folly and making commentary about what I’m observing. Not a judgement, more a record. And through this, I’m dissecting the internal force underneath the system or structure that’s making us and this world be what it is. Sometimes I think I can see glimpses of it, and then the interesting part is trying to show that. How can I make that visible and, consequently, come to understand it myself? The force that’s hovering underneath the superficial.

Having lived in Iran during a time of revolution, war and propaganda, I’ve developed a very sceptical way of looking at things. I don’t just accept the superficial. I don’t just trust what the media says. I’m always questioning the motivation behind a story and trying to find the thing we aren’t immediately able to see within a situation. Then the question becomes, how do I expose that in my work?

Some historical symbols or visual images do capture this or contain this information. As Dante said, “poems and literature are beautiful lies”. This has become a title for one of my works. Dante felt there was more truth embedded within cultural artefacts like literature, poems and visual art than in factual or historical accounts. I think this is my interest in the history of images and history itself. It’s always changing as we dig and find new civilisations or new ideas and as a result our present changes, which impacts our future.

History is also used to justify terrible behaviour in the present. The notion of a golden age that never was is weaponised, let’s say in England with Brexit, or the US, and making America great again. To me, that’s really interesting—the idea of a negotiation with history. It’s the reason for the title of the show, The Changing Past.

HB: We almost get to know history from the way it impacts the present, the way events are now unfolding. Something else that I also wanted to talk about is the evolution of your practice, how you feel your work has matured and what you’ve learned.

When I look back on my earlier work, I find that I still like it very much. It represents moments of breakthrough. At this stage of my career, it feels very important to me to keep up the quality of my work and to continuously improve my skills. It’s like trying to continue remembering how to use my hands to execute certain techniques that have become important over the years.

AB: I always tell people that it’s not getting easier; it’s actually getting harder over time.

HB: It’s about always trying to get better, preserving everything you’ve learned along the way while also trying to have the works appear new, different and evolved.

AB: That brings me to thinking about time, and my relationship to attempting to make works that stand outside of time, or are timeless. If a piece addresses something essential, something that eternally reccours, it can hold a timelessness. I’m sure you feel the same as I do in terms of thinking about how a work will withstand the test of time. I don’t think about the reaction a new painting might receive now, and am instead focused on the impact it might have in 100 or 200 years. It will live longer than I will, so I have to consider how it will communicate in the future.

Great art of the past has done that. It’s proved itself 500, 600 years on, 4,000 or 5,000 years beyond its creation in the case of ancient Mesopotamian and Near Eastern art. That kind of art is my high-bar example and I feel like I’ll keep working for as long as I can to try and reach it.

I think it’s important, as an artist, to look outside of time. To consider the whole trajectory of art history across continents, to question where you stand within it all.

Ali Banisadr’s solo exhibition, The Changing Past opened at Victoria Miro, London, on 10 October 2023.

Huma Bhabha’s first institutional exhibition in France opened at MO.CO. Montpellier Contemporain on 17 November 2023.

Written by Bella Bonner Evans

This feature originally appeared in Elephant #49.

buy it here