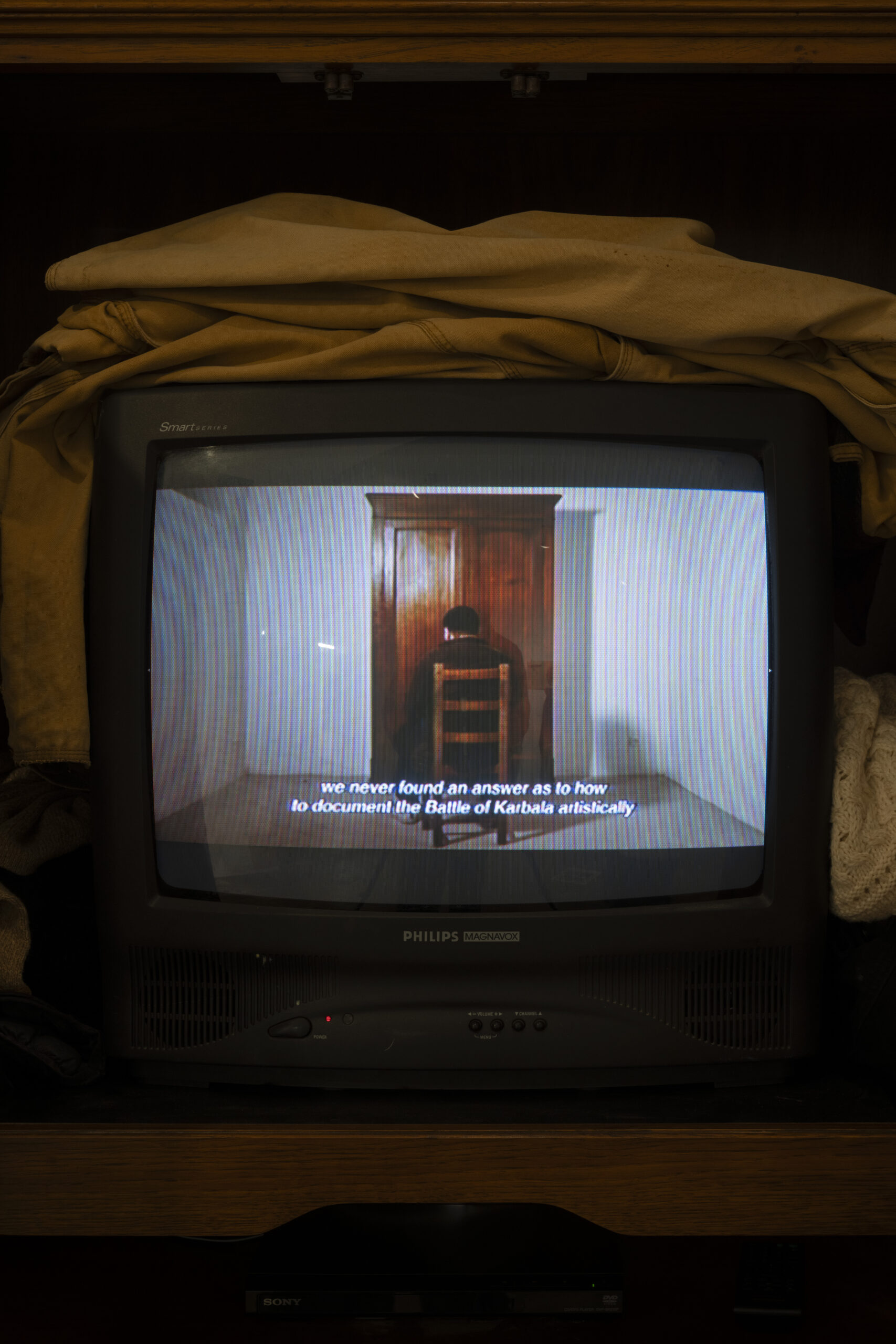

Ali Eyal is an Iraqi artist living and working in Los Angeles, CA. He recently closed a solo show, …retrieving an Obscured Present/Presence, at BELLYMAN, Los Angeles. The show’s grasp on materiality is articulate and tactical. Walls lined in manila folders, a single palm spathe laid out under rows of fluorescent lights, a lone standing armoire atop a dingy Moroccan rug; Eyal’s immersive environment is tinted with a melancholic degradation, simulating a landscape of war.

Eyal grew up on a farm in a small town south of Baghdad. His childhood was riddled with asymmetrical war and Walt Disney. At age 9, he lost his father and four uncles. Eyal, being the oldest, and his mother were left to support their family. His youth was polluted by the distant sounds of bombings, and he was eventually left with no other choice than to flee. After his exile, he monitored his home from the same satellites the US Military used to plan their attacks. He watched as his family’s farm, home for many years, was destroyed and turned to dust. However, Eyal has since looked up the coordinates of the farm on Google Maps and, to his surprise, found images of the same farm perfectly intact and enduring weather changes, as if nothing had ever happened.

As one wanders through Eyal’s show, they’re faced with narratives that are intentionally geared to pose the question, “Do I understand this story?” The disorienting yet comforting landscapes encourage the viewer to piece together fiction with nonfiction and reality with fantasy. By doing so, one is left questioning all displays of realities, news and histories.

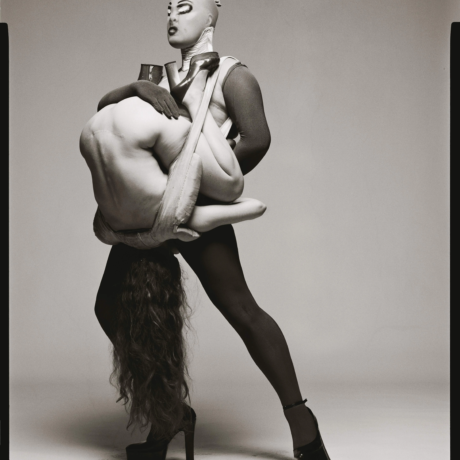

Eyal’s work is built from personal and collective memories of war; his imagery is fragmented but poignant, mirroring the impact that trauma has on cognition. retrieving an Obscured Present/Presence is tangled between Eyal’s autobiographical presence and augmented versions of self. Eyal poses a phantom figuration of sorts. He evokes a feeling of absence through physical objects: domestic, native and found, that would’ve been presumably destroyed in the path of war.

Eyal’s sculptures serve as a simulation of memory, bending what the viewer believes to be true or not, much like the difference between his family’s farm presentation on Google Maps and its true form. Eyal’s work is ghostly, like writing a letter to one’s mother and putting so much pressure on the pen that every word one writes is carved into the wood table forever.

Eyal’s show is laced with hopeful momentum, resembling his once-nomadic lifestyle. For a while, Eyal’s artistic practice progressed in a state of constant immigration and was faced with the challenge of maintaining leisure and space. He recounts that his work had to remain small as he moved from place to place, seeking permanent residence. It was only several years ago, when Eyal settled into Los Angeles that his work could expand and occupy wall space.

The subtext of Eyal’s work is anchored between fantasy and reality. His work is, ironically, a physical manifestation of erasure. Eyal reworks memories through languid gestures and unarticulated bodies. His paintings are fluid and explosive; they remind me of Robert Crumb’s drawings.

One of Eyal’s first artistic inspirations was Palestinian political cartoon artist Naji al-Ali, most famous for developing the Handala, a symbol of Palestinian nationalism. Eyal and al-Ali leave us wondering, where do the arts fit into the context of war? How is art impactful as a form of criticism and even resilience?

“The absence of my image constitutes a dialogue with the missing persons within the lost villages and destroyed houses because a house is like a face, too.”

Eyal’s work is allusive and vivid and lives between the dichotomy, reading as a dream (or nightmare) like state. His fictional and non-fictional memories are the skin and bones of his figurative body of work. Eyal sees his anthology as a stolen book, each work as a page unfolding onto one another. Ripped, burned and then re-read as a biography or maybe even the headliner of the daily paper. “I am a walking cemetery,” Eyal laments.

Written by Gwyneth Giller