Editor-in-Chief Tschabalala Self and artist Dread Scott discuss the All African People’s Consulate, a conceptual artwork taking the form of a bureaucratic office at the 60th Venice Biennale.

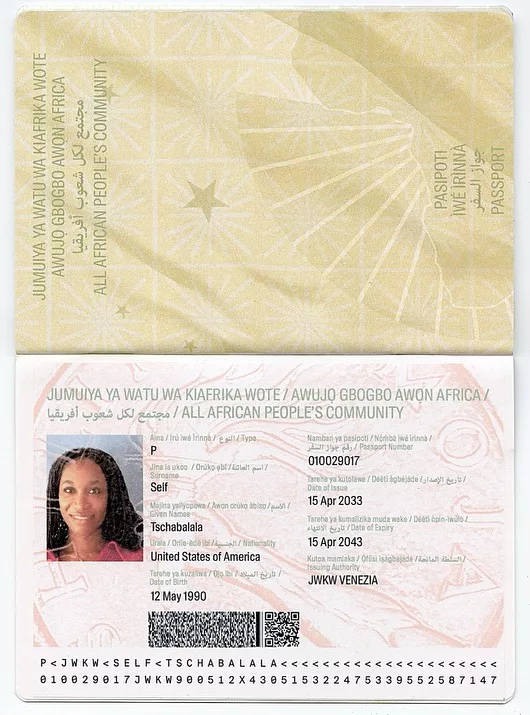

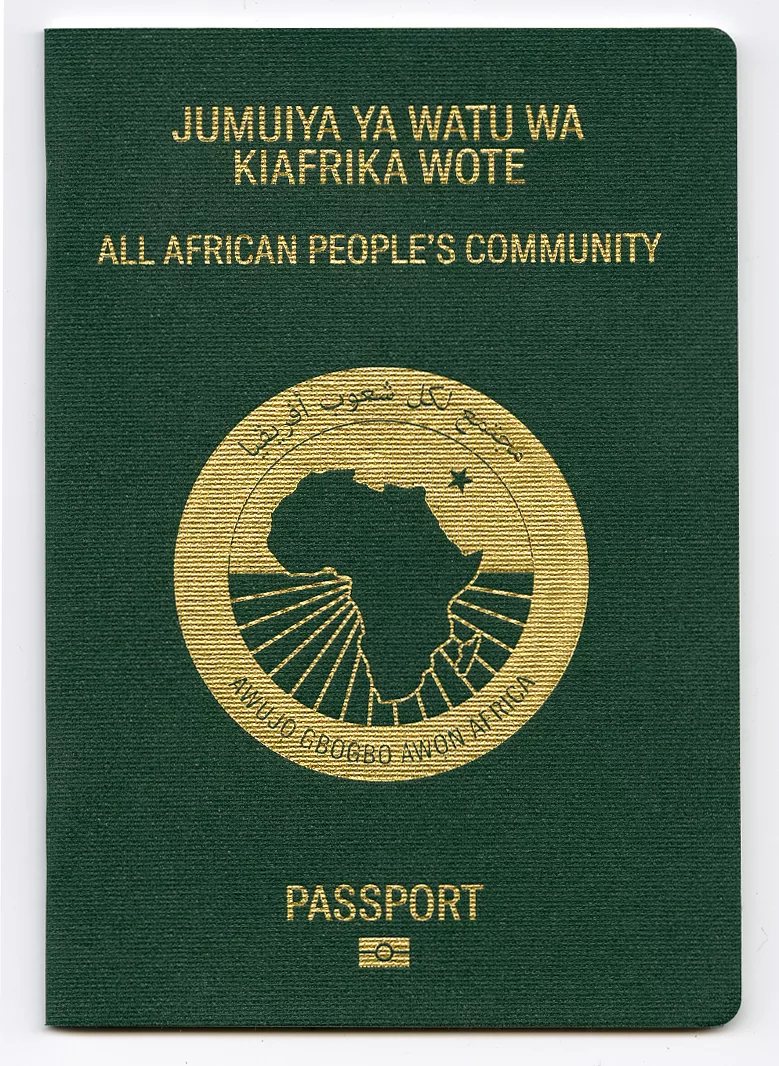

The consulate functions as an invented Pan-African, Afrofuturist union of countries, promoting cultural and diplomatic relations. In a departure from traditional immigration barriers, the consulate stands as a welcoming beacon, offering visitors a space for dialogue, interaction, and, for those of Pan-African descent, the possibility of acquiring an All African People’s Community passport — all others are welcome to apply for visas.

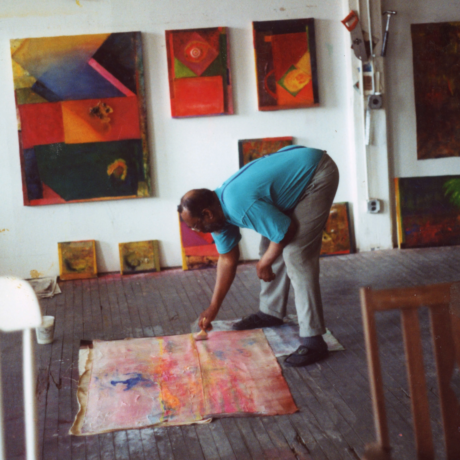

The project stands in a long history of activations, performance and happenings organized by Scott, who consistently optimistic visions of the black-future through mining and representing the Black-past. Some of Scotts most notable previous projects include: What is the Proper Way to Display the US Flag, A Man was Lynched by Police Yesterday and Slave Rebellion Reenactment.

The All African People’s Consulate was conceived by Dread Scott and curated by Paul Bright with the support of Wake Forest University, Cristin Tierney Gallery, The Africa Center, and Open Society Foundations. The project is currently installed at Castello Gallery, a collateral event space for the Venice Biennale.

Tschabalala Self: Is this your first time in Venice?

Dread Scott: It’s my first time showing in Venice, but I’ve been here a couple times before.

TS: How did you happen upon doing your project in this space?

DS: The project has been in genesis for about a year and a half. Paul Bright, the curator, told me that Wake Forest was interested in curating a project with me. The space they wanted to pursue was near the Peggy Guggenheim Collection. We were all set for doing it there and then for reasons completely unrelated to the project, it fell through. So we had to scramble and quickly find a space. We talked with various people in Venice who revealed that Castello Gallery happened to be available. I was like this is great, let’s do it here!

TS: Am I correct that this project is almost like a fictional Pavilion for the African Diaspora?

DS: Oh, it is a real Pavilion. A fictional place; so I just described it as the All African People’s Consulate. It is a real functioning Pavilion for an imagined Pan Africanist Afrofuturist Union of countries.

TS: What countries do you imagine to be part of this? I get the concept, I often refer to “Black America” as a fictional country in my own work.

DS: We’re real, you can touch me. I’m a real person.

TS: True. A real country, but an unrecognized Nation? What other nations do you see being part of this consulate?

DS: So, All African People’s Consulate is for the all African people’s community. Anyone can be part of that. Well, anyone that is currently a citizen of any of the 54 countries in Africa, as well as anybody who’s of African descent, regardless of where they live. So it would include people of any ethnicities who live in the continent of Africa, but all Black folk in Jamaica, in the United States of America, in Belgium, wherever; those are the people who are part of the community.

TS: I think that’s really helpful in establishing the boundaries, or lack there of — for this nation. When people come to visit the exhibition, what can they anticipate seeing? What kind of artworks can they anticipate engaging with here?

DS: It’s a conceptual artwork, the project as a whole is the artwork. So it’s not that they’re individual pieces. The main focus is the experience which people have when they come to the space. There is a staff as any consulate would have, a staff who warmly greets guests with,

“This is the All African People’s Consulate, welcome! Why did you come in today?”

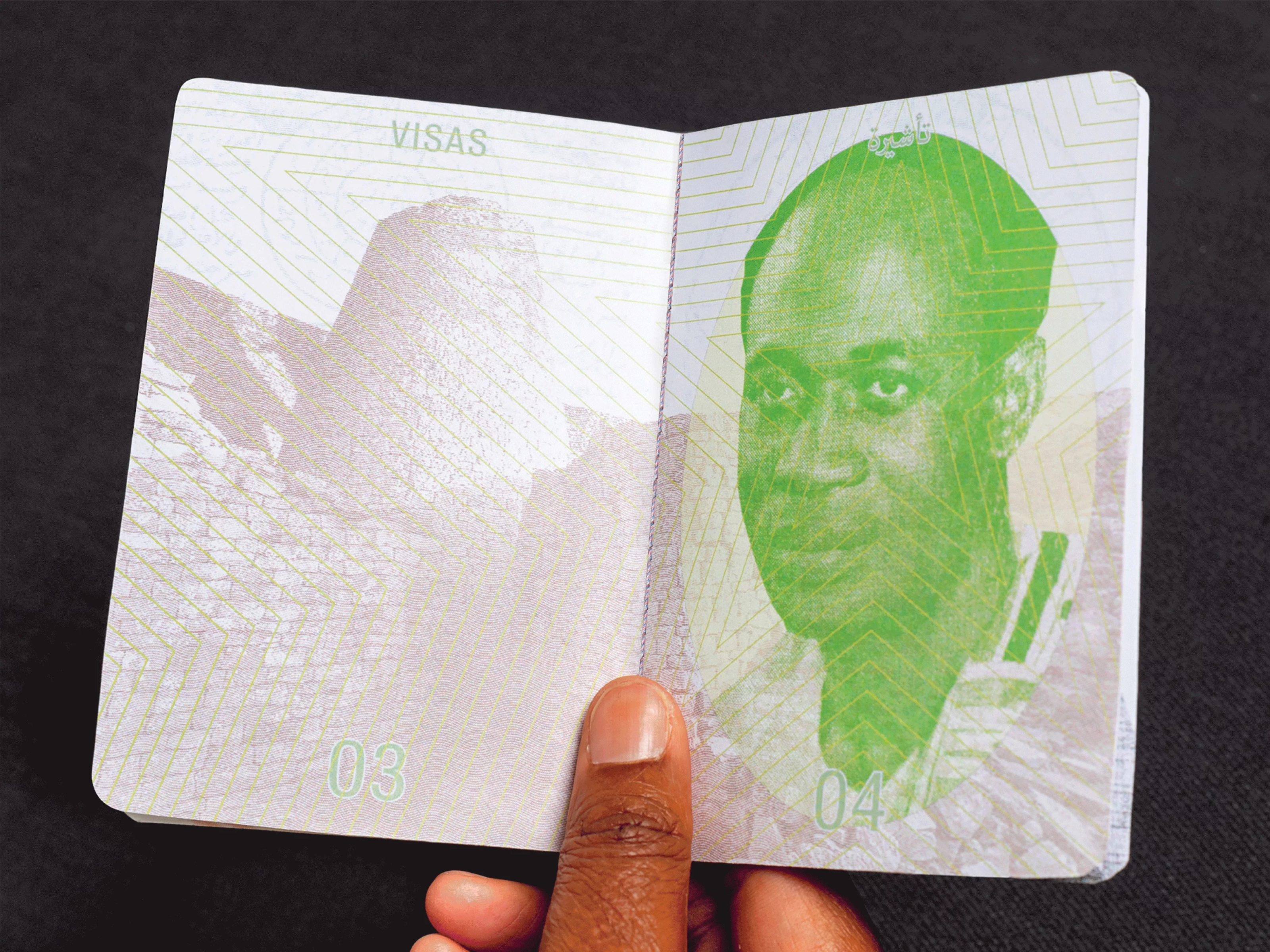

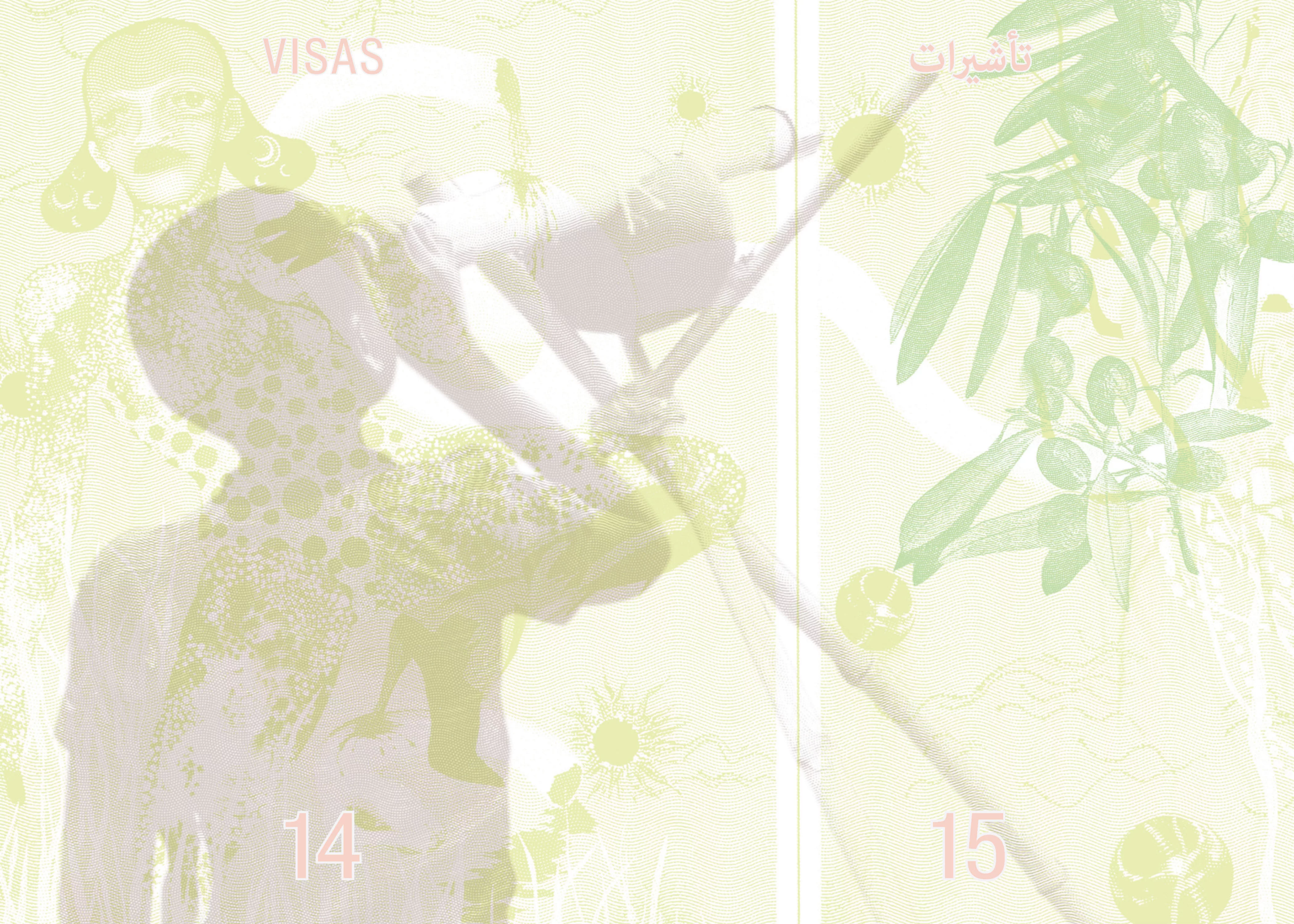

If visitors say, look, “I’ve heard about this, I’d like to apply for a passport or Visa.” We’ll facilitate that — we have a beautiful passport to offer. If they are of African or Afro-descent, regardless of where they live, they can apply for a passport and they will be welcome into the community. There’s a brief dialogue which explores both their history and relationship to Africa, and their history of migration (what brought them to Venice). If you’re African, you’ll get a passport and it will be personalized. It’ll actually be like a real passport, it will have your photograph, birthday and name.

“If you’re not of African descent, you can apply for a visa.“

TS: I like that idea.

DS: We welcome visitors. Conversations with them will be a similar conversation to passport holders. We’ll ask what their relationship to Africa is, what’s their history of migration, where are they from and what brought them to Venice?

If they’re from Nicaragua, the questions following that might be different than if they are from Belgium or the Netherlands or the United States or France or England. Each of which had a Colonial relationship with Africa in terms of slavery.

“We’re not holding people accountable for what their great, great, great, great grandparents did but they do have to acknowledge what the relationship between their country and the continent of Africa is.”

We’re not saying, “you’re English so fuck you,” it’s not that like that. What did England do? Why is it they speak English in South Africa or in Nigeria? Why are they trying to get rid of French in Niger? Those are the questions that would be brought up. People aren’t going to be held accountable for stuff that happened in the past, but they will have to acknowledge it and have a conversation about it. If people are like, “I’m not with what people did 150 – 250 years ago. I’m not with that,” then come on in and welcome! But if they’re gonna say, “hey, I’ve got a bunch of money and want to hire some cheap labor in Africa,” then you have to stay home. We don’t need that. We have plenty of good stuff in Africa that you all stole and we want to keep it. We don’t need you to exploit us, but if you want to come build, learn, enjoy some nature, that’s cool.

It is sort of a globalist community, but it is also set in the future. We aren’t going to emphasize this but when you get your passport, it will actually be established about eight years into the future from today, same with the VISA. It’s not something a lot of people will notice, but it will be like you’ve gotten a document and an experience from the future. You’re not living in the present.

TS: Is it fair to say that this project’s concept is aspirational? Something that we could manifest?

DS: Well, sort of both. It is something that is aspirational. Something of the future and of the past. Pan Africanism has roots going back to the early 20th century, but a lot of where its modern incarnation comes from is the 1950s and 60s. With the founding of Ghana and the Liberation struggles that led to the independence movements, there was a real vision of an African solidarity that wasn’t based on entrepreneurship and capitalism. And right now, to the degree, Pan Africanism exists. We’re not trying to go back to the past, I don’t want to say, “let’s Resurrect The Ghost of Kwame Nkrumah,” that’s not what this is about. It’s about trying to encourage people to overcome all the differences that have been put down on Africans and explore how can we actually live in a way that gets to the future.

You look at what happened recently in Senegal, there was an election where the youth said, “No, we are not having Macky Sall stay on for yet another term,” which is actually really cool they did that. But it looked like an Independence movement with a vision that didn’t get carried through past the 1960s or 70s. And so I’m hoping that people both on the continent, and beyond can say well,

“How do we actually get free? What does a liberated Africa look like and not just in opposition to other communities?”

We want that to run through our ethos, to be a celebration but also rooted in culture. Also looking beyond that because there is a real question of: How do some of the aspirations of even Africans moving within Africa get realized? I mean, it’s actually really difficult for somebody from South Africa to visit Ivory Coast or Chad.

TS: What questions should we be asking to get to this point of liberation?

DS: So how do people have freedom of movement? How do you actually get to a point where it’s not about everyone for themself, but where it’s actually people collectively trying to get free and be part of a global community?

I will say, this is an art project. Even if I had all the money, time, and resources of 50 countries, solving some of these things would be difficult. It would be a real challenge.

This is something that I, as an individual artist, have been in collaboration with other artists and friends of mine. We’re hoping to put forward something that people can connect with. Hopefully people can run with it and it can be part of broader conversations. You see the AAPC flag (the All African People’s Consulate flag), which is something I designed and you see work on the walls by the great artist, Lisa Hunt, who unfortunately died recently.

TS: Yes, I was made aware of Lisa Hunt’s untimely passing recently.

DS: Did you know Lisa?

TS: I know her work and I saw a lot of her work for the first time in the Netflix movie Leave the World Behind — the apocalyptic one with Mahershala Ali. I remember thinking how elegant they were — absolutely beautiful work.

DS: Yeah. So the thing is, patterns and textiles are really important across the African continent. But the patterns that they have in Ghana are different than they have in Nigeria or South Africa. So when I was designing a flag, I wanted to honor and reference all patterning, where I could have some patterning that is rooted in that tradition, but not tied to a particular place.

TS: I wanted to ask you, just so the people can know, where in the diaspora do you hail from?

DS: I’m African American, I grew up in Chicago. My parents on my mom’s side I can trace back into slavery. On my dad’s side, I can only trace back to my dad, I really don’t know. From DNA tests, I know I’ve got a lot of blood from Nigeria, Benin, and a little bit of Senegambia. I’m also about 45% European, but I feel connected to Africa in a way most African-Americans are. You know, a cop will pull you over because he knows damn well, you’re black.

TS: I think this happens a lot in the West, especially in America, the conflict between people of different nationalities within the African diaspora — “diaspora wars,” for lack of a better term. What can you say to people that are engaging in these sort of debates? Can you explain to them the importance of Pan-Africanism in 2024?

DS: There are lots of different ways people understand Pan-Africanism. Peter Tosh has a song that says: no matter where you come from, if you’re a black man, you’re an African. If you come from the Church of God, you’re an African. That whole point unites us. Africa, as a concept and continent, was divided by colonization and enslavement. That’s actually what welded a continent into what we understand as modern Africa.

There’s amazing performance art going on in Kinshasa, it’s the best performance art I’ve known, what’s going on in the United States is not nearly as interesting as that. We were literally just having lunch and we bumped into someone we vaguely knew, who’s this Cameroonian artist named Snake. To me, that performance is more interesting than some of the figurative, representational painting which we’re seeing in a lot of art fairs in the West. When I was talking to Snake, he said he wanted to go to New York. I asked, “Why?” to which he said, “Tupac, Biggie, you know.”

The culture that came out of the South Bronx is part of a broader African diaspora and African Continental conversation. Years ago I read an interview with Fela where he said, “I want to be like Malcolm X.”

“He drew political inspiration from Malcolm X, he was looking to Africa, the Mecca. He was a visionary political leader welded in the bowels and guts of America.“

TS: Last question regarding the show, what is the immigration process like here at the consulate, what can hopeful citizens expect when applying for their passport?

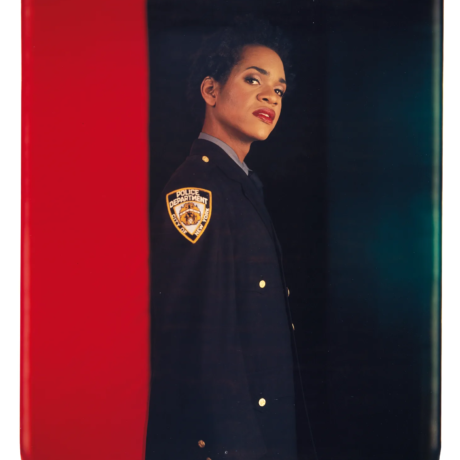

DS: First off, they already are part of the community. Part of why I wanted to do this was because I knew that there was a significant African community in Italy, and Venice in particular. Many people have papers, some of them don’t. Some work in restaurants and are often looked down upon and not made to feel very welcome in this society which some of them have been living in for many decades or more. So I partially wanted to do this for the Afro-Italian community that’s here.

There’s a level of bureaucracy here, but the bureaucracy is actually functional and it’s going to serve the purpose of creating a community. This is a project about community. This is a welcoming space, you can see all of these chairs where some people are just sitting and hanging out, we want that to happen. People can come use the Wi-Fi here, people can come use the bathrooms here. We want people to just come and have conversations.

TS: That’s very cool, thank you Dread. Can I apply for a passport now?

DS: Of course!