Courtesy Joshua Liner Gallery, New York

It’s early on a sunny Friday morning and I’m in the heart of New York’s art hive, Chelsea. The mood is weirdly quiet and contemplative. A palpable sort of tranquillity hangs thick in the air, like in those precious few moments before the sun rises over the groggy morning-after scene of a house party. Aside from the brown-bagged bottles spilling out from the city’s iconic green trash cans (no fresh air here), business cards and exhibition printouts litter the streets from the stampede of autumn openings the prior evening. It’s my first time back in the States since Trump was sworn into office, and Chelsea seems hardly worse for wear: there’s no tangible difference save for the fact that every one in three (or so) galleries you’ll venture into has some Trump-themed work on offer.

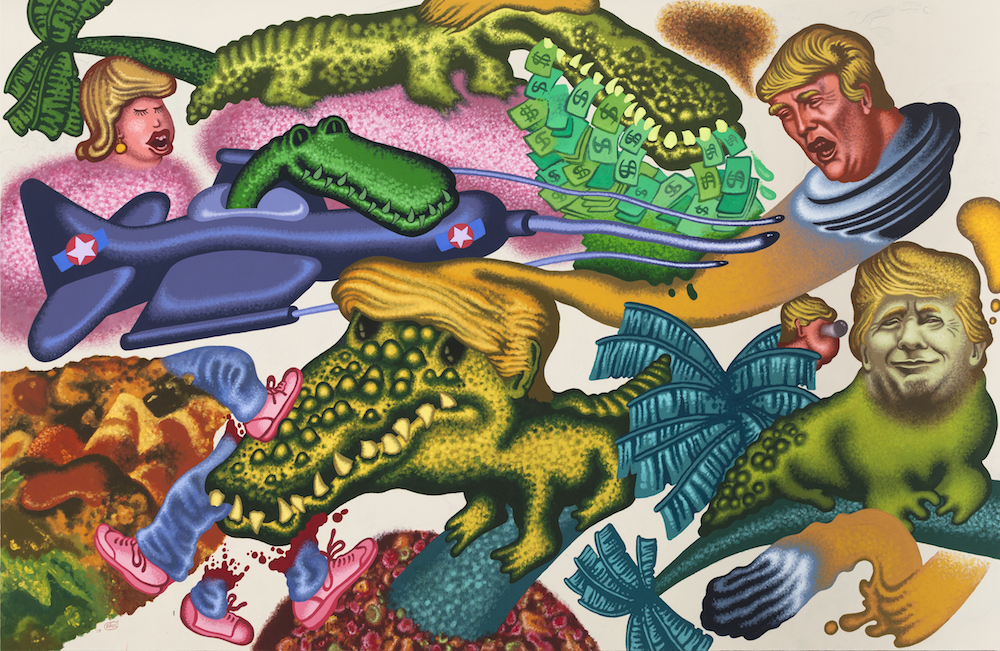

Entering the light-washed exhibition space of Mary Boone Gallery, the prophecy rings true: I find myself nose-to-snout with a lumpy green gator sporting an all-too-familiar platinum blonde comb-over. His beady black eyes betray no flicker of empathy for the three bloody limbs decked out in neon pink Kicks caught within his mottled jaw. A decapitated head of Hillary Clinton, eyes closed and lipsticked mouth agape, floats in a cloudy pink haze at the top left of the colossal painting, while a flying saucer carrying Trump’s orange mug narrowly dodges heat-detecting (or bullshit-seeking?) missiles spouted from a fighter jet with yet another furious gator at the helm.

Ronald Feldman Fine Arts

No stranger to controversy, Peter Saul’s newest show, Fake News, feels especially charged: a double-shot of disdain seeps through the viscous outer layer of political absurdum that is Donald Trump in Florida (2017). The reptilian-infested, tropical-hued scene of a post-apocalyptic Trumplandia makes a strong case for the continued sauciness of so-called “post-Trump art”—though it’s a good deal more settled than some of the riotous work framing the jittery period leading up to the election, like the group show Why I Want to Fuck Donald Trump at Joshua Liner Gallery in Chelsea, which featured collaged genitalia portraits of both candidates and a grave labelled “TRUMP”, for starters.

So, it’s been a long eight months. What’s changed in the art world, if anything? Is there any sort of pattern or system to sort the prolific volume of Trump-themed art drawn out into the world from the dystopian arch from mid-2016, when he was announced as the Republican Presidential nominee, to now? On the one hand, any attempt to give order to work responding to the once-unfathomable concept of Trump’s actual touchdown in the White House feels absurd in its own right. This challenge is heightened, of course, by the fact that his Presidential career is still an act in process. Can there possibly be such a thing as “post-Trump” art, while he bumbles around in office and we brace ourselves for another (long) year?

Photo: Christopher Allen © Jaime Muñoz

From New York to LA to Tehran and, most recently, over to London, the sheer number of exhibitions organized in direct response to Trump’s rise to power and ultimate win is so mind-boggling that it deserves, at the very least, a stab at classification. As art and politics become ever more intertwined and terms like “activist art” and “protest art” bleed into everyday art speak—sprinkled into reviews and press releases, serving as the theme of biennales and exhibitions—how ought we distinguish between the many voices of resistance?

It’s certainly worth noting the track record of artists such as Peter Saul, whose political practice precedes Trump by a good half century and will doubtless outlast him, versus those artists who have hopped on the bandwagon. More often than not, the “post-Trump” practice of artists who were on a totally different track a year ago is flat satire, the visual equivalent of a one-liner, and pretty often it appropriates from art history to make its point. One example: the photographic work Piss Trump by sculptor James Kelsey that copies Andres Serrano’s 1987 Piss Christ. Prior to having his “world shaken” by Trump’s election, Kelsey had been making abstract sculptures for over twenty-two years.

EPW Studio/Maris Hutchinson

Though an obvious copy, Piss Trump and its ancestor hit on the powerful link between bodies and politics, and the subversive potential of the former’s refusal to sit pretty within the boundaries set by the latter. Unlike Kelsey, who is, needless to say, a white, cis-male artist, the 2017 Guggenhiem fellow Cassils—one of the contemporary art world’s leading transgender voices—unveiled Monumental at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts in Soho. At the heart of the show is PISSED (2017): a minimalist structure holding two hundred gallons of urine—all of the liquid the artist has passed since the Trump administration revoked Obama’s order that allowed transgender students to use the bathroom of their chosen gender identity.

Like turning up to a protest rally, using one’s practice as a platform for resistance puts the artist at risk of being caught in the crossfire of the outrage and fear brewing within this electrified political moment. The degree of risk depends on the body to which this voice is attached, and the particular sets of privilege or vulnerability that social and political power structures exert upon it, on both local and national scales.

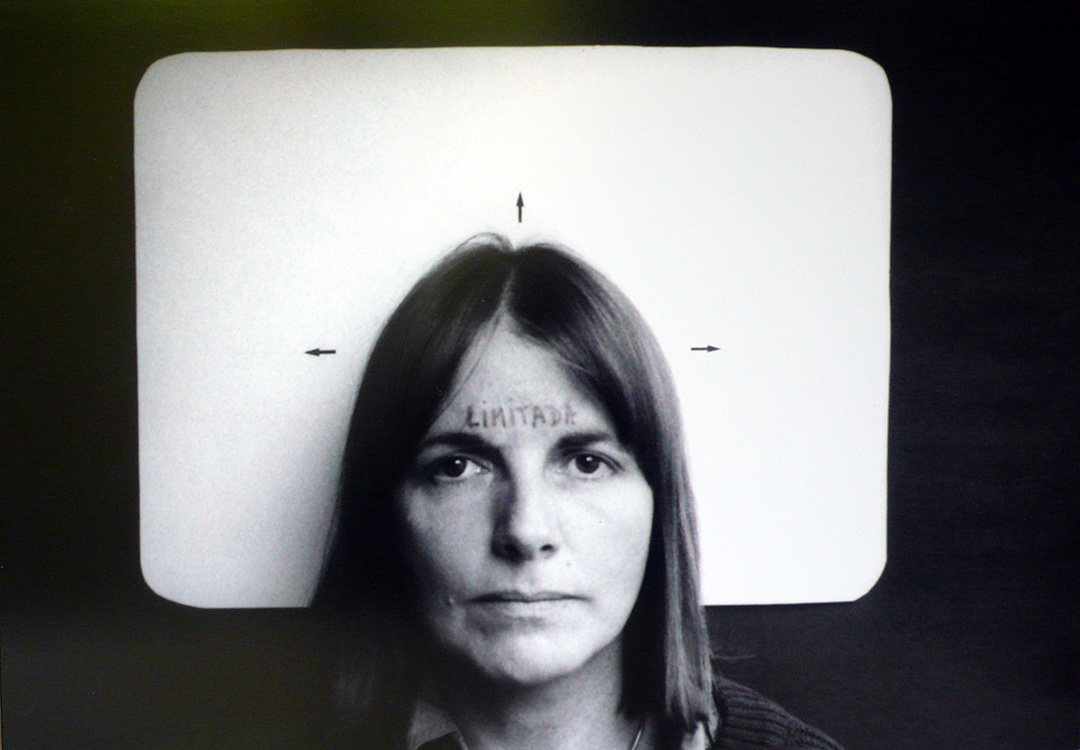

Courtesy Alejandra Von Hartz Gallery © Marie Orensanz

Finally, when we talk about post-Trump art, we must keep in mind the power structures inherent to the art world. Protest art has de facto powers of porosity, where the urgency of its message can squeeze into, play around with and ultimately undo these forces in subversive and productive ways, ways that can be propped up by the art world infrastructures and economies. Consider, for instance, the Nasty Women exhibition launched initially at the Knockdown Center Queens in early 2017, just a couple of weeks before Trump’s inauguration. Coalescing the anger and fear felt by many women in America, the concept of the show was simple: anyone who identified as female could submit work, and as long as it measured under 30 by 30cm, it would be included in the exhibition. These works would be put up for sale for less than $100. In its three day lifespan, over seven hundred artworks were sold, and a $35,000 profit was donated to Planned Parenthood. Nasty Women has continued to travel internationally, with seventy-two exhibitions and over $200,000 raised to date, with its most recent manifestation cropping up in Hackney Wick last month.

On a more formal frontier, the annual Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA exhibition currently unfolding across Los Angeles tackles issues of borders and immigration to encourage a timely and mindful conversation about the so-called “artwashing” of LA’s Latino-dominated neighborhoods in recent years, including the hipster dives of Echo Park and Silver Lake. With the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) legislation terminated by the Trump administration the weekend before its opening, Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA took a particularly hard look at the deep-rooted historical and cultural connection between Los Angeles/Latin America vis-à-vis the half-million “dreamers” currently living in California, whose future livelihood is at stake.

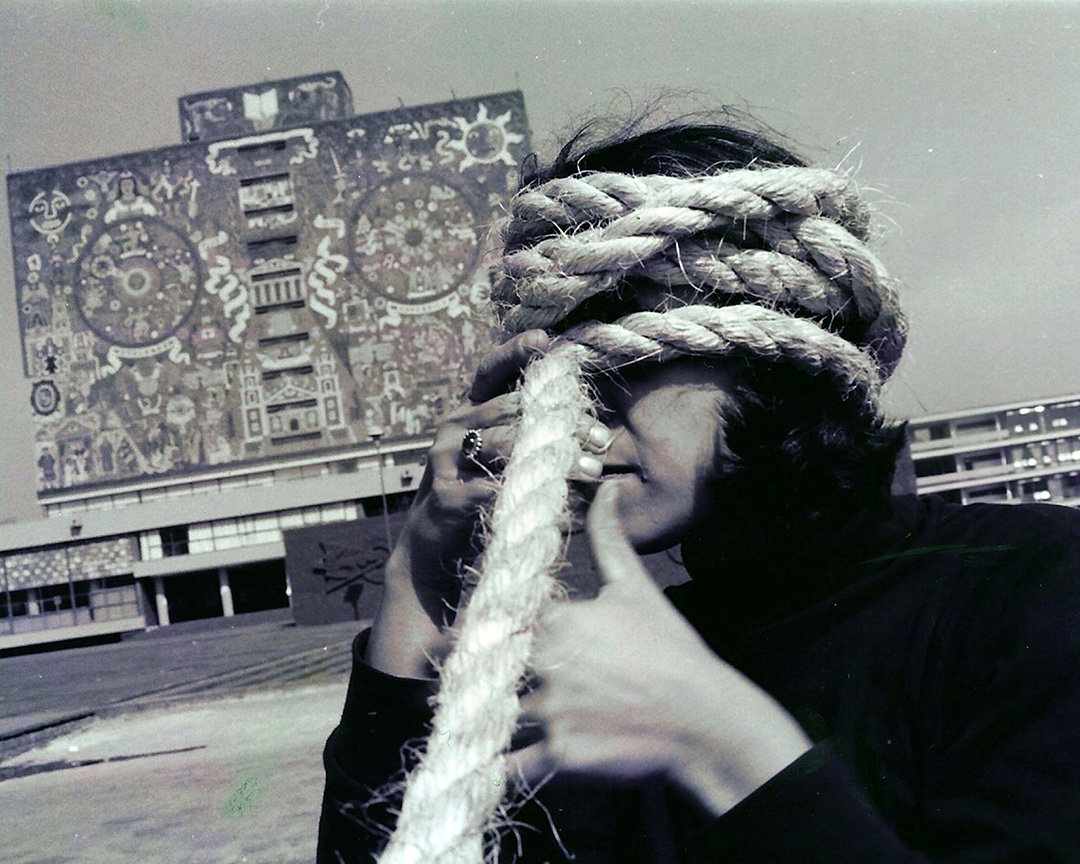

Andrea Ferreyra, Torbellino/Whirlwind, 1993

Photo: Gabriela González, courtesy Andrea Ferreyra

As Trump’s administration makes increasing advances to undo the small victories achieved for minorities underneath Obama and promotes unprecedented levels of racially-motivated domestic terrorism (the very latest of which, occurring recently on the Vegas strip, has claimed at least sixty lives–the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history), the fluctuations of privilege and risk inherent to protest in the age of Trump can literally mean the difference between life and death. Between the urine-filled Soho galleries and scaly, coiffed gators, real danger lurks, behind poetics as much as protest. It’s therefore crucial to point out these distinctions at every turn as we delve deeper into life post-Trump and a new period of contemporary art emerges in its wake.

Ronald Feldman Fine Arts