Sofia Hallström talks to Allison Katz about her curatorial practice and her current show ‘In the House of the Trembling Eye’ which offers a fresh perspective on the interconnectedness of art across centuries.

“There’s nothing that determines an artwork as contemporary just because it was made today,” Allison Katz tells me. We are in Katz’s south London studio discussing her latest exhibition In the House of the Trembling Eye (May 30 – September 29, 2024) at Aspen Art Museum. Her practice broadly encompasses painting, posters, installation and ceramics, exploring the intersection of autobiography, commodity culture, information systems, and art history through diverse imagery, playful wordplay, humour and recurring symbols. “I think it’s important to challenge the idea of the contemporary. In some respects, the 2,000 years between a Pompeiian fresco fragment and an Alice Neel painting isn’t that long. In the context of deep time, it’s like yesterday,” she says. Her work addresses the ambiguity of subjectivity, combining texture and site-specific installations to engage viewers.

In 2022-23, Katz was among the inaugural fellows of Pompeii Commitment, a new contemporary art program recently initiated by the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, co-curated by Stella Bottai who is also Senior Curator at Large at the Aspen Art Museum. When Aspen Art Museum Director Nicola Lees and Bottai approached Katz with an invitation to develop an exhibition of works borrowed from local collections in Aspen––to celebrate the Museum’s 45th anniversary and the 10th anniversary of its Shigeru Ban-designed building––Katz had just visited Pompeii. “It all made perfect sense despite seeming so random,” Katz laughs.

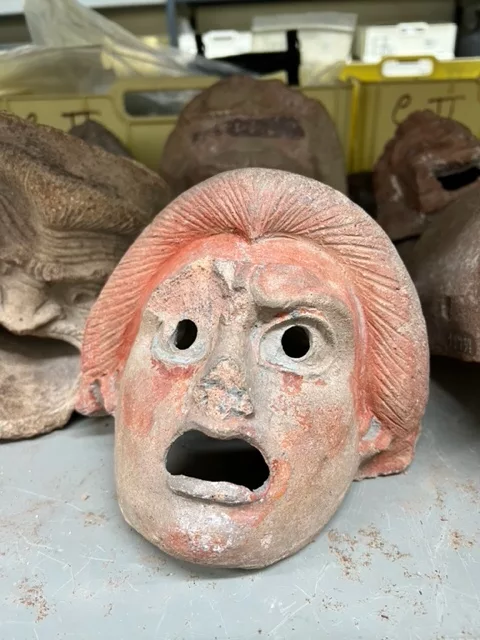

In the House of the Trembling Eye, organised in collaboration with the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, juxtaposes her recent works with over one hundred works on loan from private collections in Aspen, as well as a series of fragments of ancient Pompeian frescoes. Katz’s connection with Pompeii dates back to her teenage years. “I went to Pompeii for the first time when I was 15, an impressionable teenager just getting into art. Seeing those frescoes in situ had a lasting impact. I was shocked by the immediacy of the mark making, it just didn’t feel old,” she explains.

Katz’s fellowship at the Archaeological Park of Pompeii provided her with access to storage spaces typically closed to the public. “The storages are like living archives because nothing is packed away; everything is open and visible on shelves. Seeing a shelf with ancient tweezers, like fifty tweezers all laid out, each encrusted with volcanic ash, was incredible. These are things that jolt you into the everyday,” she reflects. Her time in Pompeii deepened her understanding of the ancient site, influencing how she viewed and curated the exhibition. “Initially, I looked at the paintings individually, focusing on the details, expressions, and temporality of the marks. But this time, touring the ruins with an archeologist, I realised that ancient houses functioned like museums—blurring the lines between public and private spaces. This made the paintings feel very contemporary, in the way that their content and their presentation communicated intention, identity and aesthetics in a way that feels both changed and continuous,” Katz notes.

The public and private are similarly explored in In the House of the Trembling Eye. The exhibition layout is modelled upon the ancient Pompeiian townhouse, the domus, and was developed by Katz with assistance from the architect Caitlin Tobias Kenessey, her cousin and long-time collaborator. “We always approach architecture as a container for meaning. This space allowed us to explore how paintings and other artworks can inhabit and transform a shared environment, creating a dialogue between past and present,” Katz explains. The exhibition is built to guide visitors viewing perspectives with through-way views, raised floors, partitions, and curtains. Much like an ancient Roman house inspired by the Greek memory theatre, the exhibition uses spatial design and vivid imagery to evoke and preserve memories. Katz notes that in the domus, “all is choreographed to make a theatre out of the house, and spectators of everyone else.” Reflecting on Katz’s ideas, I thought about Giuliana Bruno‘s concept of architexture, as it highlights the narrative and emotional dimensions of architectural spaces. In the domus, room arrangements and detailed decorations create an architexture that tells a story and engages the senses. Bruno sees architecture as interacting with memory and time, with buildings acting as repositories of history and personal memory. The layout in In the House of the Trembling Eye raises fundamental questions about how images occupy shared spaces and shape our experience.

The exhibition spans the entire Aspen Art Museum, and is divided into nine rooms, beginning with a prologue (‘The Street’), followed by the six rooms of the domus, ending with an epilogue (‘Eruption’) and a post–script (‘Gradiva’.) The sequence of the house starts with the atrium (central courtyard), then moves into the tablinum (“office”), triclinium (the dining room, literally translates to “three couches”, a reference to the ritual of eating while reclining in groups of three), peristyle (a small garden), cubiculum (“bedroom”) and culina (“kitchen”). The atrium includes a new painting by Katz titled Eternity (2023). Two men are depicted installing a skylight, their figures sharply silhouetted against a bright, cloudless sky as they gaze down into the room below. The image plays with perspective, illustrating the surface depth and frame as a portal into another dimension. Pompeiian frescoes equally played with depth and illusion, using thresholds like frames, doors, and windows to challenge the limits of painting and invite viewers to explore beyond. This self-reflexive approach continues in painting, questioning its own nature and pushing its boundaries through the act of looking and reflecting.

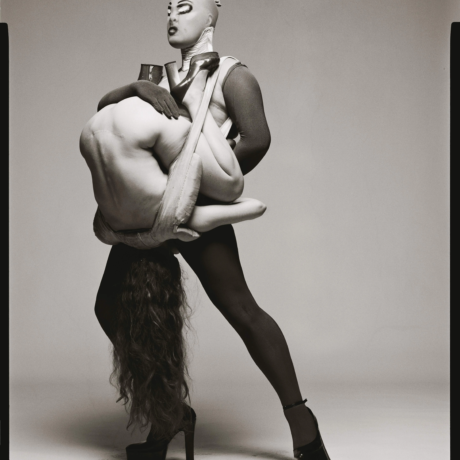

The exhibition displays works by just over fifty artists, including Maurizio Cattelan, Marc Camille Chaimowicz, René Daniëls, Marlene Dumas, Jana Euler, and Sylvie Fleury. Katz selected these pieces through a combination of visits to private collections when she was in Aspen, and remote perusing back in London, working in close creative partnership with Bottai. The museum team conducted site visits on her behalf, sending back digital images, measurements and also news about loan requests, conveying whether or not her wish list was possible: “with an exhibition this large, I had to adapt and pivot, but amazingly I got the majority of what I asked for.” Observing how people live with their collections was fascinating: “My favourite spots to look at were above the bed and in the bathroom—it was eye-opening,” Katz shares.

The Aspen Art Museum has a history of inviting artists to curate exhibitions, emphasising the importance of local engagement. “In some cases, the works displayed in the museum normally live two blocks away from the museum! Something very local, inspired by something very far away… the connective tissue of individuals and how they can bring seemingly disparate interests together…” Katz reflects on the unique circumstances of her curatorial role: “It wasn’t originally my idea to curate a show at Aspen! It was an invitation with very unique constraints (local works) to celebrate a specific building (architecture) of an artist–founded institution, a non-collecting museum (more like a Kunsthalle model) that takes risks by allowing artists freedom and trust. I needed to think bigger about museums altogether since I am not a curator! And the task at core was how to take the private back into the public. I literally curated it as an extension of how I paint.”

Recurring motifs in Katz’s work, such as her initials A.K. and the cockerel, reflect her interest in the interplay between personal and collective narratives. “All narratives are both personal and public […] To me, painting is the single plane that can combine this supposed separateness,” she muses. Katz challenges the conventional distinctions between contemporary art and historical artefacts. “We have hyper-accelerated ideas about time and the contemporary, but I’m not sure that’s so useful. The contemporary can be found in any time period because it’s inside the viewer who is alive now,” she says.

We discuss the physicist Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time which challenges the concept of time as a linear sequence. The concept of time, Rovelli says, “has lost layers one after another, piece by piece” and we are left with “an empty windswept landscape almost devoid of all trace of temporality…” Katz’s work similarly blends past, present, and future, creating a layered narrative that transcends linear time and invites viewers to experience a multi-dimensional temporal landscape. New paintings titled Puberty (2024) and Gradiva (2024) both depict female figures, one young and one older, set in motion through a series of image breaks on the canvas plane. By staging the images as a montage, they converge into movement and multiply. Katz recognises the importance of working beyond the level of mere superficial representation and attempts to bring a degree of living, breathing reality into her work and curatorial practice, in line with Italian humanist and artist Leon Battista Alberti’s comparison of a painter to a ‘carpenter, dismantling a house with care’. In the House of the Trembling Eye converges temporalities, eschewing traditional art historical narratives in favour of a more fragmented, cyclical approach.

The setting of the exhibition in Aspen is remote and tucked deep in the Rockies. “This exhibition marks the first time these fragments have been displayed with contemporary art in the US—a new experience for the audience and highly specific to this location,” Katz notes. The exhibition has garnered positive reactions from visitors, many of whom return for multiple visits. “My favourite feedback is that people are going back to see the exhibition again. It means they want to start again and delve deeper. The free admission aspect also resonates with me, as it encourages repeated visits,” Katz shares.

In the House of the Trembling Eye offers a fresh perspective on the interconnectedness of art across centuries. As Carlo Rovelli aptly stated, “Reality is not what it seems,” and indeed, Katz’s approach to her own practice and curation goes beyond conventional perceptions, drawing from diverse sources across centuries. The exhibition’s success lies in its ability to transcend time and context, creating a dialogue between ancient and contemporary works. As Katz concludes, “Understanding that painting, though it has a fixed surface, changes dramatically based on context, proximity to other works, and the viewer’s perspective reinvigorated my belief in painting as a mutable, living entity.”

Words by Sofia Hallström