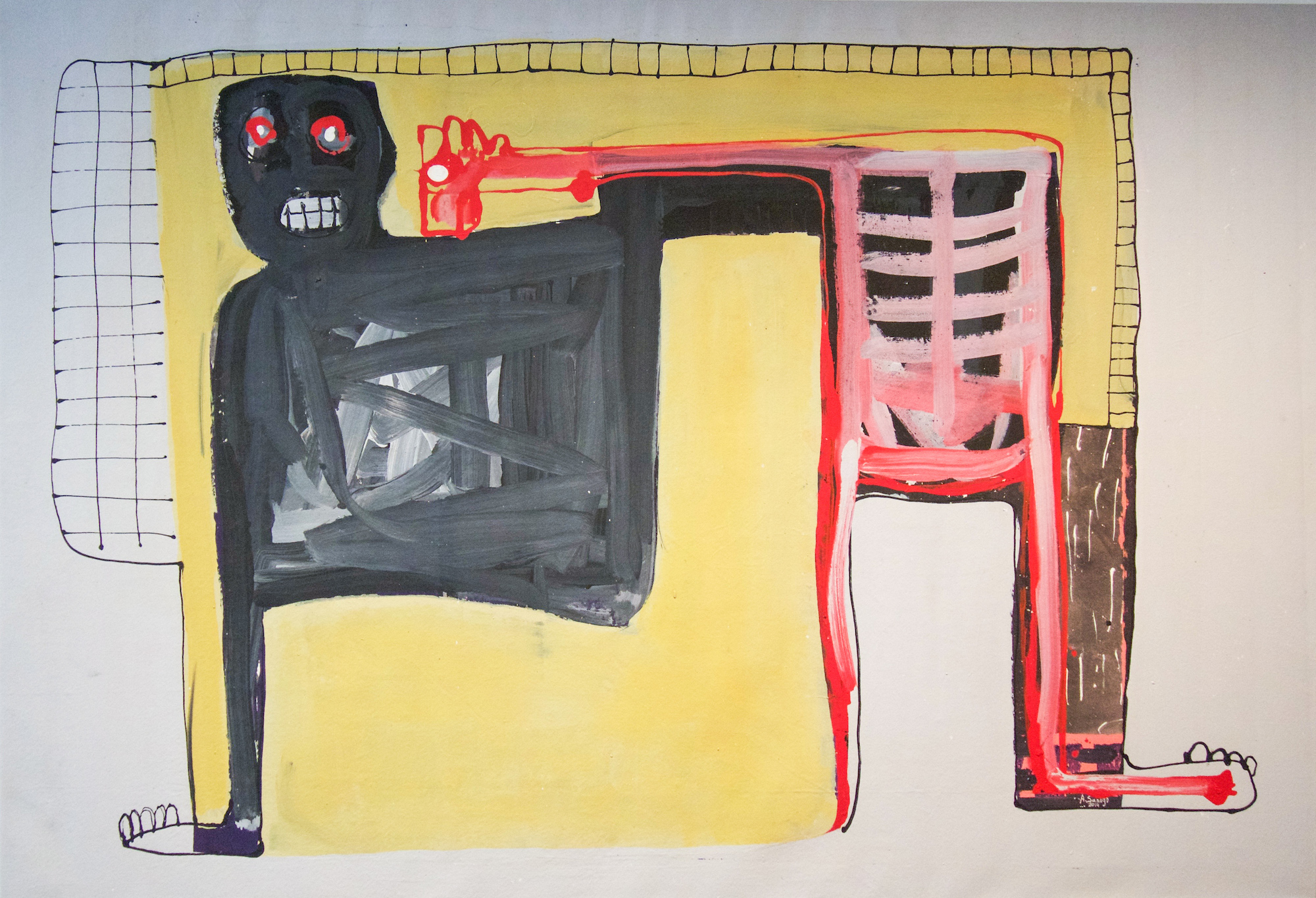

Sanogo’s earliest experience of drawing was outside a television shop in his home town of Ségou, and perhaps this was the origin of his method of seeking his subject matter through television. Sanogo is both an artist and a tenacious critic of society, declaring: “Not all food should pass through the stomach. Food that passes through the mind is as important. This is symbolized in my work by the importance of the head.”

How did you become a painter?

In 1997–98 I passed the entrance exam to get into the INA (Institut National des Arts) in Bamako, Mali, and graduated in 2003. That brought me among artists. The desire to paint came to me in my second year of art school, through one of my professors who encouraged my curiosity about painting. My inspiration comes from the world around me, from the ways in which people behave and think. I am a part of this world, and questioning myself leads me to challenge what I see. Painting is for me a means of projecting this questioning onto a specific space.

Who are the expressive yet enigmatic figures that people your works? Why are they so often distorted and even headless?

The expressive figures featured in my work represent the relationships a person will have with himself, with his surroundings and with other people. I distort them because we all have flaws: I can’t create perfect forms because they don’t exist. I behead my characters because nowadays we’re faced with such a dismal reality that it feels as though we’ve lost our heads. Everything is muddled; nothing is clear. The so-called leaders, whether political, economic or humanitarian, have nothing to offer, and people are bewildered. I see all this as a body without a head, without the ability to think or project a vision. Today’s world leaders love nothing more than to deceive people and lead them towards an uncertain future. So, according to me, our head is missing!

“I behead my characters because nowadays… it feels as though we’ve lost our heads”

Can you tell me a bit about your use of colour, which feels at once joyous and menacing?

Each painting is a playful struggle in which I engage when I’m faced with a piece of cloth. There are some works that I manage to subdue early on in the process, and there are many others that resist me, though in most cases I will eventually succeed. The way I paint is by building up and destroying until I achieve the shapes I want.

You have said: “Mali needs me.” What role does the artist play in a country where a large proportion of the population lives in poverty?

If Mali is in need, it isn’t because I am Amadou Sanogo, but because the political, economic and social system is driving a whole generation of young people to give up, and my own questioning has made me realize that running away isn’t a solution. We need to face up to our reality in order for things to change. That is why I felt moved to become a leader for young artists, who I believe are among the worst off. Now I’m getting a bit more international recognition, I’m trying to gather the younger generation around me.

Could you tell me a bit about Badialan 1?

is an artists’ collective that I founded in 2014 to bring about a change in people’s mindsets and attitudes. In view of the many problems faced by young artists I met in Mali, notably the diffusion of their work and the lack of opportunities for dialogue with other artists, I began to think about sharing my own slightly wider exposure with others. And so we decided to set up Atelier Badialan 1 (AB1), naming the studio after the Badialan neighbourhood where we congregate. The collective is made up of about fifteen visual artists all working in the studio and sharing resources with others such as art critics, gallery owners and promoters we might know. And it’s such a mad set-up that we’ve even been joined by several playwrights and musicians: in other words, our studio belongs to all artists.

This feature originally appeared in issue 29

BUY NOW