The year was 2007. The Arctic Monkeys headlined Glastonbury and Amy Winehouse was in the charts with Rehab. Hedonism floated in the air as the global financial crash teetered on the horizon. In 2007 I was working part-time at American Apparel in London’s Carnaby Street, aged seventeen.

It was only a matter of months since American Apparel had expanded from their origins as a wholesale clothing company—founded in 1989 by Canadian Dov Charney—into the international retail market. They boasted of their ethical production line based in LA, and all goods came with a label to prove it: “Made in the USA”. With their newly established presence on the high street, the brand quickly gained a distinctive reputation for its range of simple yet sexy t-shirts, leggings and underwear.

Suddenly, these stretchy cotton goods were everywhere. For art school students and young creative professionals in particular, it became the brand of choice. It was no small feat to manoeuvre plain t-shirts, formerly sold cheaply to screen printers and uniform companies, into the orbit of the fashion-conscious consumer. That the company did so with such rapid success—over three years they grew 440 per cent—can be put down to a mixture of good timing, clever branding and downright exploitation.

“It was no small feat to manoeuvre plain t-shirts into the orbit of the fashion-conscious consumer”

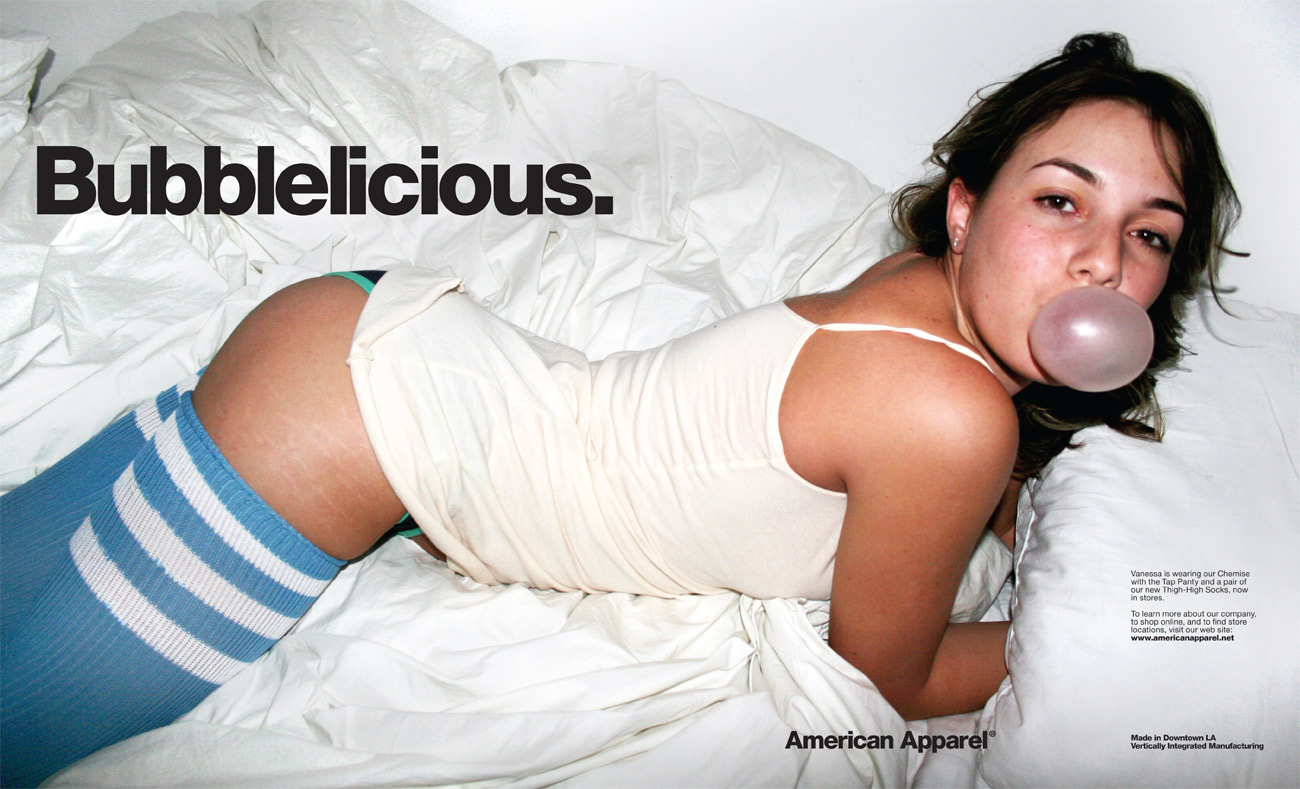

During my time working on the shop floor at American Apparel—the first job I ever had, after submitting polaroids of my teenage self in tight leggings and an oversized t-shirt—I became attuned to the provocative imagery that defined the brand. With a heady mix of intimate point-and-shoot photography, snapped seemingly off the cuff and frequently set in the bedroom, and models who looked more like art students, they claimed to redefine beauty standards.

It was an easy line to swallow at a time when photographers such as Terry Richardson and Richard Kern reigned supreme, and Vice magazine was in the ascendant. American Apparel regularly took out full page adverts in Vice, and the two became associated with a new social class: the hipster. Women were considered either fun and liberated enough to “be cool” with the semi-nudity, degrading poses and innuendo of American Apparel’s advertising campaigns, or they were boring, old-fashioned and unenlightened.

Shot by Charney himself, the adverts were brash and aggressively suggestive. One focused on a model’s crotch area only, cutting out her face, while others featured models bending over in short skirts so as to reveal their underwear beneath. Adult entertainment trade magazine Adult Video News even cited the American Apparel website as “one of the finer softcore websites going”.

I never modelled for American Apparel, but I know several who did. It was a point of pride in certain indie circles at the time to have done so, in a pre-Instagram era when many male photographers included a submission page for aspiring models on their website, often with no offer of payment. Charney himself cast amateur, inexperienced models in this way, as well as visiting his stores worldwide to select employees for campaigns. The fact that the balance of power was so starkly tipped in Charney’s favour was rarely discussed, and his behaviour created a toxic working culture in the stores that encouraged staff to conduct inappropriate relationships with supervisors.

“With intimate point-and-shoot photography and models who looked more like art students, they claimed to redefine beauty standards”

Most will know how the story ends. Dov Charney stepped down as CEO in 2014 following multiple sexual harassment cases brought against him, and American Apparel filed for bankruptcy the following year. “There had been stories about Dov for years and years, but they had been very hard to pin down because every time an employee made a complaint against him it went to arbitration,” Allan Mayer, former co-chairman of American Apparel’s board, told the Guardian in 2017. “But when we were able to conduct a more forensic investigation with an outside investigator we found videos and emails from him on the company server that, well, to call them inappropriate would be an understatement.”

To look back now at my time on the American Apparel shop floor just over a decade ago is to appreciate just how much has changed. The Me Too movement has brought the pervasive abuse of power into the light, and young women have been given the chance to stand up for themselves and represent themselves as they wish, reclaiming ownership from the male gaze over their own sexuality. I wish that the quiet, image-obsessed girl that I was back then, so keen for approval, could have known what was to come.

The American Apparel adverts capture a time when female submission and silence were encouraged, and normative gender ideals were peddled under the guise of the counter-culture. As Jenny Holzer has famously stated, the abuse of power comes as no surprise, and there was nowhere to go but down for a company whose ethos so brazenly ignored this fact.