AAA Library. Photo: Kitmin Lee. Courtesy of Asia Art Archive.

Climbing laddered streets up from Sheung Wan’s markets to the neighbourhood of Tai Ping Shan, the freneticism of all below fades into birdsong. The small quarter, perched in the “mid-levels” of raised ground between the water’s edge and the Peak, was the first location the British took on Hong Kong Island in the 1840s, towards the end of the First Opium War. The British named it then “Possession Mount”, but the Cantonese translates, more accurately today, as “Peace Hill”. Sloping lanes bring you eye-level with the middle floors of pastel-coloured apartment buildings and tree branches, into a rare air of laid-back living within a metropolis that has accelerated beyond the likes of London. Walking through Hollywood Road Park, elderly residents do their daily exercises and terrapins float in the pavilion’s pond. The modest working community established here through the twentieth century is now joined—in some cases, no doubt, replaced—by independent cafés, art spaces, and boutiques, which are still several steps away from the commercialism of Central.

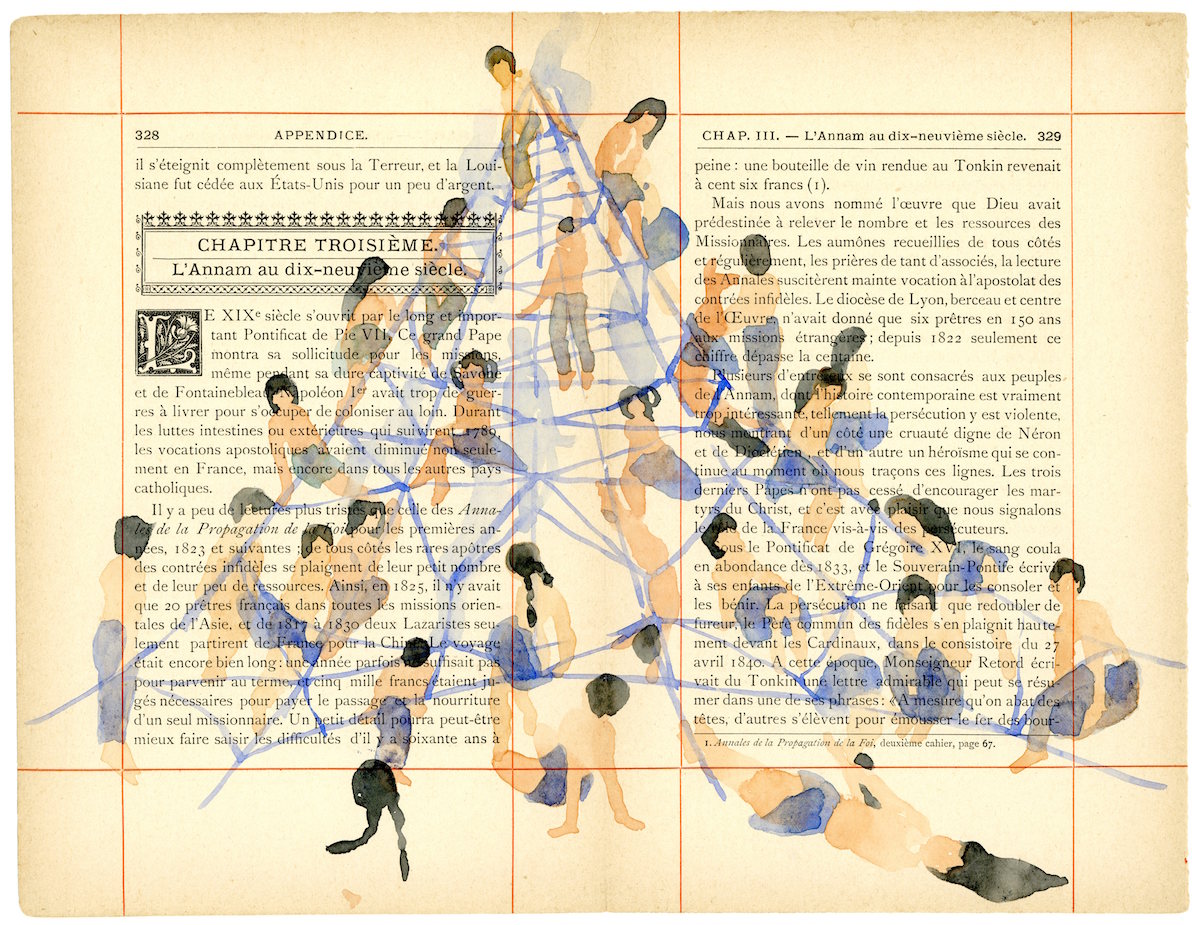

This centuries-spanning narrative of occupation, slum-razing, replanning, and art-assisted gentrification may not be foreign to you, but that of Tai Ping Shan has some twists and turns. High in a block a little further along Hollywood Road, the strip for dynasty antiques since the trading of the colonial era, you will find the Asia Art Archive—an extensive, ever-growing research collection connecting recent histories of art in the region. Aside from the organization’s Women Make Art History fair booth at Art Basel, discussing the status of women in the Hong Kong art world and featuring the Guerrilla Girls, the AAA library will exhibit pieces from Indian artist Nilima Sheikh’s archive, curated according to an ongoing thematic focus on movement and migration.

As the arc of gentrification tends to go, some of the early art spaces to open in Hong Kong’s oldest neighbourhood have now moved on. Para Site

, perhaps the first non-profit to set up in Tai Ping Shan in 1996, at the cusp of the British-Chinese handover, now lives in expanded premises in a tower block in North Point. Here it continues its active programme of exhibitions, discussion series and residencies, a vital place of contact between local art communities and global scenes. During Art Basel, Para Site will host the travelling exhibition A Beast, A God, and a Line, whose multitude of works, including by Gauri Gill, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Ming Wong, seek to replace the outdated “colonial cartographic coordinates” of the Asia-Pacific region.

“Here is a rare air of laid-back living within a metropolis that has accelerated beyond the likes of London”

Another site where the pace of the city dwindles to a grid of calm is Cattle Depot Artist’s Village, near Kowloon Bay. (You can take the ferry directly here from North Point, if you’re coming from Para Site.) The low-rise brick-and-tiled studio complex is nestled in the 13 Streets neighbourhood, with its hum of car mechanics, metal workshops and South Asian grocers. Leftovers of performance artist and studio resident Frog King’s props line the path along with plants and parts of installations. The depot houses a couple of project spaces open to the public; notably Videotage, founded in 1986 and dedicated to the local media art movement. Videotage will present a screening of video works from their collection at the fair, in conjunction with South Korea’s Nam June Paik Art Center. The Future Is in the Past program will trace Nam June Paik’s influence on video artists during China’s ’85 New Wave (a period of artistic experimentation following the repressions of the Cultural Revolution in the 1960–70s), as well as the contemporary impact of a burgeoning generation of moving image artists in Hong Kong and in mainland China.

With an MTR station due to open later this year, the low-key shabbiness and residential chatter of Videotage’s surroundings may not last long. The speed of urban redevelopment in Hong Kong over the past twenty years has been voracious, and both the government and real estate developers realize—in that familiar tale—that culture can fuel change in the fabric of an area, or act as the excuse for it. On the western point of the Kowloon Peninsula one such multi-billion dollar development has been in the works for a decade, led by Foster + Partners and covering forty hectares of reclaimed land. The West Kowloon Cultural District, an “art park” with various signature-architected venues within it, has been controversial for its drain on funding, requiring figures that existing arts organizations might only dream of, with critics stating that the plans seem more about the branding of the city than for the sake of art.

“Come for an impression of West Kowloon’s scale, stay for the serious views over the harbour”

Nonetheless, the mirrored facade of M+ Pavilion, which will in time become the smaller sibling of M+ museum of visual culture, is the first art centre to open to visitors. The current exhibition is an audiovisual installation by Samson Young, expanded from his commission for the Hong Kong pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Meanwhile the nearby Elements supermall showcases the side of Hong Kong culture that revolves around high-sheen retail, air-conditioned atriums, and shopping zones themed in pseudo-harmony with the earth’s elements. Come for an impression of West Kowloon’s scale, stay for the serious views over the harbour.

Back across the bay, the temporary Harbour Arts Sculpture Park, coinciding with and close to Art Basel, boasts around twenty public sculptures set off by the skyline. As Hong Kong-based critic Hera Chan points out in her Ocula article, In Memory of a Free Public, the park’s location overlaps with that of the first sit-ins which ignited the pro-democracy Umbrella Movement in 2014, where peaceful protestors were eventually dispersed with force by the police. In this context, Chan reads Morgan Wong’s marble tombstone Time Needle (A Time Capsule of Some Day) (2018), as marking urban reclamation “as a series of fresh graves and fresh wounds”. The sculpture park presents yet another example of how art and capital cajole in the contemporary metropolis (Hong Kong not being exceptional in this, although it is accelerative); of how recent and longer-arching histories are rapidly covered over to renew the image of a square of grass, a neighbourhood, or a whole region.