Marlee Miller is an academic who specialises in Gladiators. So who better to provide commentary on the historical and artistic motifs that shape Ridley Scott’s epic? Miller provides us with the necessary context that is often overlooked. This is the first of two articles on these films; the second will be published after Gladiator II comes out November 22, 2024.

I consider myself among the lucky who saw Ridley Scott’s Gladiator in theatres when it was released twenty-four years ago. I never thought a sequel was in the cards, but it’s finally happened and, yes, I booked my ticket a month in advance! As a Roman archaeologist who specialises in gladiators, it thrills me that the public is still excited to embrace ancient history and to, yet again, become spectators to one of history’s most infamous phenomena.

This article will not just be a summary of the first film, but include commentary on art and historical motifs and topics to provide needed context. While there are still gaps in our knowledge of the ancient world— particularly the world of gladiators—film and TV often take creative liberties to fill in those blanks and feed the imagination. That said, not every historical film or TV show has to be a documentary or literal recounting of primary sources. Like the Romans in the amphitheatre, I want to be entertained! This is the first of two articles on these films, with the second to be published after the release of Gladiator II on November 22, 2024.

People

Emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161 – 180 CE) did oversee a war on the northern borders of the Roman empire, fighting against tribes attempting to encroach on Roman territory, mostly in what is now Germany and Austria, across the Danube River. The military camp (castrum) Vindobona, mentioned in the film, is now in the heart of modern-day Vienna, where a great museum houses extant remains.

Marcus Aurelius came to power as the son-in-law—and later adopted son—of his predecessor, Antoninus Pius (r. 138 – 161 CE). Marcus Aurelius’ son, Commodus (r. 180 – 192 CE), was indeed widely disliked, his personality and ruling style standing in stark contrast to his father’s. Commodus was ultimately assassinated by his own bodyguards, the praetorian guard (cohortes praetoriae)—think of the character Quintus, Prefect of the troupe, and his men—not in the amphitheatre, as depicted in Gladiator. Ancient writers often mentioned, in a pejorative and mocking tone, how Commodus enjoyed fighting in the amphitheatre—essentially “cosplaying” as a gladiator. They saw this as his attempt to gain a false sense of strength and victory, something that otherwise eluded him.

Lucius Verus ruled as joint emperor with his adopted brother Marcus Aurelius from 161 to 169 CE, yet Gladiator is set in 180 CE, several years after Lucius Verus’ death. In the film, he is referred to as the father of young master Lucius, who is later portrayed by Paul Mescal in Gladiator II.

It’s important to note that gladiators and slaves typically had only one name, while elites had three (tria nomina): a praenomen (personal name), nomen (clan or family name), and cognomen (originally a nickname). In Gladiator, when Maximus, formerly known as “the Spaniard,” reveals his true identity to Commodus and the praetorian guard in the arena, it is crucial that he uses his full name. By doing so, he asserts his former status and highlights the inconceivable violence and injustice that have been inflicted upon him and his family.

Gladiatorial Personnel

The types, training, and infrastructure of gladiators happen to be the focus of my doctoral dissertation. Gladiators were primarily slaves, prisoners of war, and criminals. It was not uncommon for a person to be captured and essentially forced into the gladiatorial world. Slaves could be sold to a lanista—gladiatorial troupe manager, think Proximo from the movie—as a punishment (known as damnati ad ludos) until Emperor Hadrian (r. 117 – 138 CE) outlawed this practice. The lanista and their trainers (doctores) were often former gladiators themselves, like Proximo, since they had few other career options due to their low social and political standing. Much like actors and prostitutes, they were regarded as infames, people of ill-repute and shame.

Ludus Gladiatorius and Training

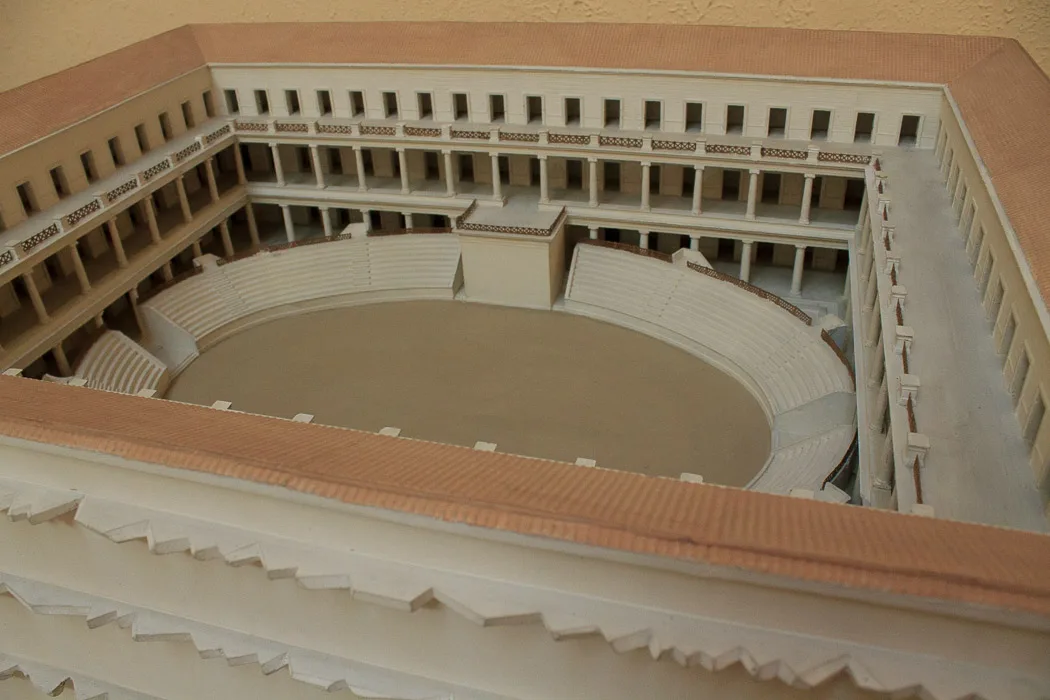

Gladiators, who were a part of a familia gladiatorial, would live and train in a ludus gladiatorius—“ludus” meaning “game” or “school” in this context. The best-preserved and most extensively excavated ludus is the Ludus Magnus, the great training school in Rome, located just behind the Colosseum.

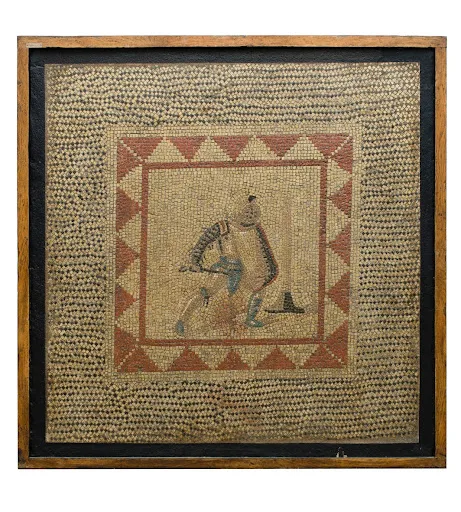

While little archaeological evidence of gladiatorial training remains, several key artefacts help us understand their practices. The use of wooden weapons, for instance, is confirmed by artefacts, such as this exceptional mosaic from Cyprus, wooden weapons from England, and literary sources like Vegetius’s 4th-century De re militari (1.11 – 13). Additionally, the technique of training of gladiators “by the numbers” against a palus—a six-foot wooden pole stuck vertically in the ground to simulate an opponent—is corroborated by Vegetius. A few depictions, including this remarkable mosaic emblema from France, also support this practice.

For an extended discussion and additional images, check out my article on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

Amphitheatres

In Roman times, the amphitheatre in Rome was known as the Amphitheatrum Flavium, named after the Flavian Dynasty (r. 69 – 96 CE), which included emperors Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian.

One theory attributes the nickname “The Colosseum” to an epigram written by the Anglo-Saxon author Bede (c. 672 – 735), in which he celebrates the Colossus of Nero—a massive bronze statue commissioned by Emperor Nero that underwent several alterations and relocations. The confusion stems from the Latin term coliseus, which referred to the statue but was mistakenly interpreted as referring to the amphitheatre.

| Quandiu stabit coliseus, stabit et Roma, quando cadit coliseus, cadet et Roma, quando cadet Roma, cadet et mundus. | As long as the Colossus stands, Rome will stand, when the Colossus falls, Rome will fall, when Rome falls, so falls the world. |

Amphitheatres were built throughout the empire’s provinces, much like the ones depicted in the movie, where fights were held before making their way to Rome—similar to minor leagues or a travelling theatre troupe before reaching Broadway. In certain regions, namely Gaul and the Greek East, existing theatres were often repurposed and renovated for gladiatorial games, adding more protection for spectators against weapons and wild animals. In some cases, entire stadiums were renovated, with one end enclosed to create an arena.

Naumachiae

Looking forward to Gladiator II, something that was not common practice, as shown in the sequel’s trailer, was the naval battle (naumachiae), where the arena was flooded and ships sailed in staged battles. While the practice originated under Nero, records show only a handful of naumachiae in amphitheatres, with just two taking place in the Colosseum: one by Titus in 80 CE to celebrate its inauguration (Dio Cassius, LXVI, 25, 1–4), and another by Domitian around 85 CE (Suetonius Domitian, IV, 6–7). These events would have been an enormous logistical challenge, especially after Domitian expanded the Colosseum’s hypogeum, the underground area used for animal storage, lifts for openings in the arena floor above, and holding fighters. With this infrastructure in place, flooding and draining the arena would have been impossible.

For such water-based spectacles, however, a purpose-built venue existed elsewhere in Rome, along with several lakes and basins in the region that could be adapted for these events. Only two amphitheatres, in Verona and Mérida, Spain, show any technology designed for water use in the arena. And lastly, it may go without saying, but sharks would not have been lurking in the flooded arena’s waters.

Written by Marlee Miller