In an increasingly digital world, where facial recognition apps allegedly store our aged portraits and smart devices eavesdrop on our most intimate conversations, a growing number of artists are presenting tech-inspired dystopias in their work. New York and Shanghai-based Miao Ying adds an even more bitter cherry on top of this potential, doom-filled future, with her commentary on drastic governmental Internet censoring, and eventual self-censorship, in her home country of China. “Self-censorship is similar to Stockholm Syndrome,” says the artist, about becoming frenemies with censorship over the last decade, since she graduated from graduate school. “I never read George Orwell’s 1984 because I live in it and it’s pretty dark already.”

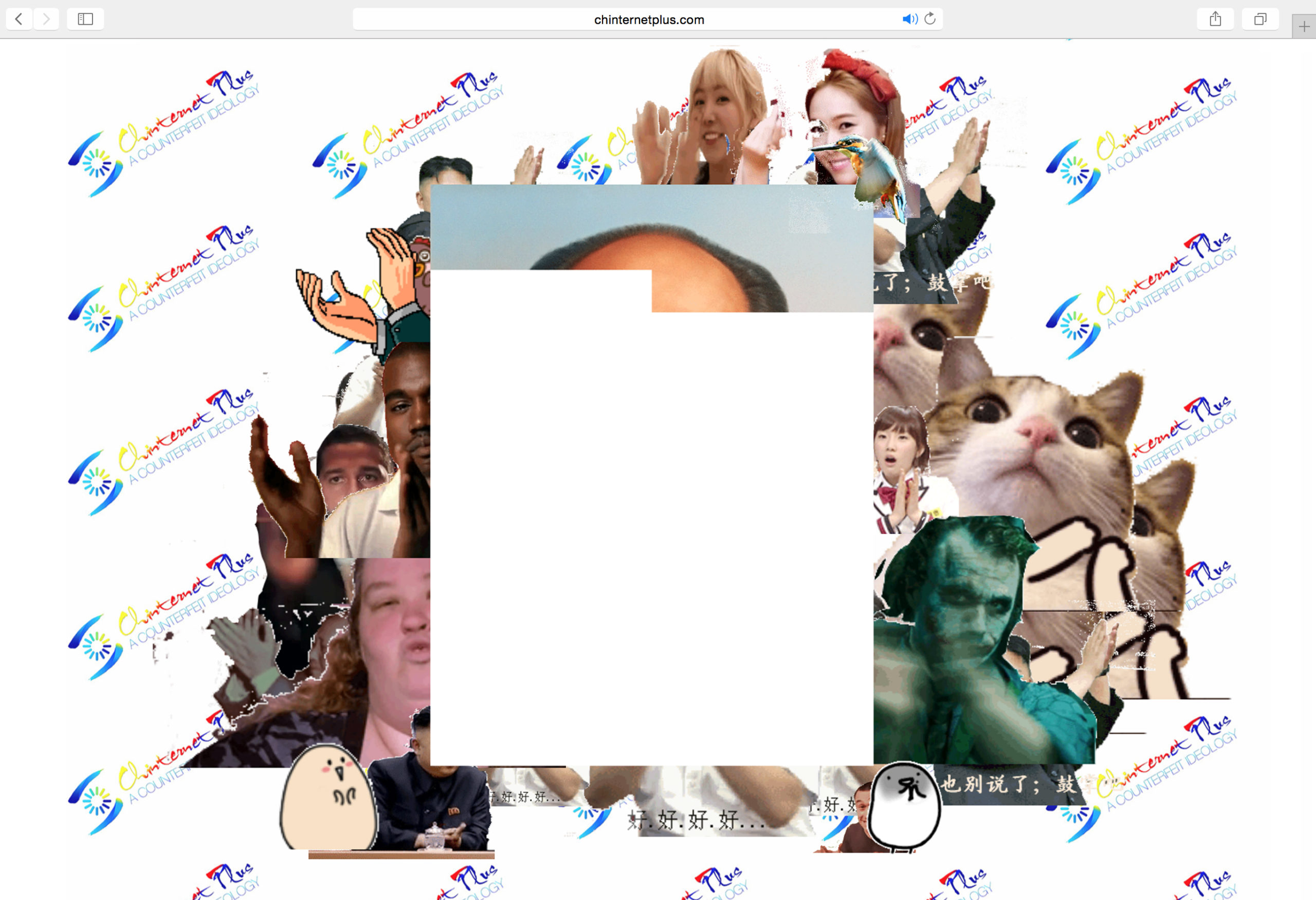

It’s easy to think censoring is wrong—few would argue with that—but the artist has been practicing ways of working with it, while playfully bending the rules. Miao showed a GIF of a half-loaded image of Chairman Mao as part of her mixed media installation Chinternet Plus in the group exhibition The New Normal: China, Art, and 2017 at Beijing’s UCCA Center for Contemporary Art. The cultural bureau, during one of their usual trips to institutions to eliminate “threat”, deemed the work inappropriate because of the clear resemblance of the former leader’s forehead. The artist’s solution was to raise the image’s pixilation to such a degree of unclarity that she was able to exhibit the work, which was about China’s economy slowly getting stuck in a manner similar to a buffering image.

“The work always starts with a digital core, which relates to a communist ideology of starting with an abstract vision”

Miao’s mixed media installations—or promotional showrooms, as she calls them—bring her web art pieces into the gallery space, but exist almost secondary to her work in the digital realm. For Miao, her work strictly “resides online” and physical installations that she has started showing at museums and art fairs result from an outside demand to prompt the audience to go to the Internet to visit the work. “The work always starts with a digital core, which relates to a communist ideology of starting with an abstract vision and adding up to build an idea,” she tells me.

At Art Basel Hong Kong in 2016, she presented a mashup of GIFs on touch screens with New Media, China’s leading digital and print publishing firm, and at the booth of her Vienna gallery Nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder. “Everything is about lifestyle now, and the installations promote a lifestyle that lives online,” she explains. “The body is absent in the work, which might make the viewer feel curious, and I use wallpaper, architecture and sound to promote the missing digital aspect, like an ad agent promoting the philosophy of a brand.”

“When I am in the US, I can see China more clearly because there, I am frustrated”

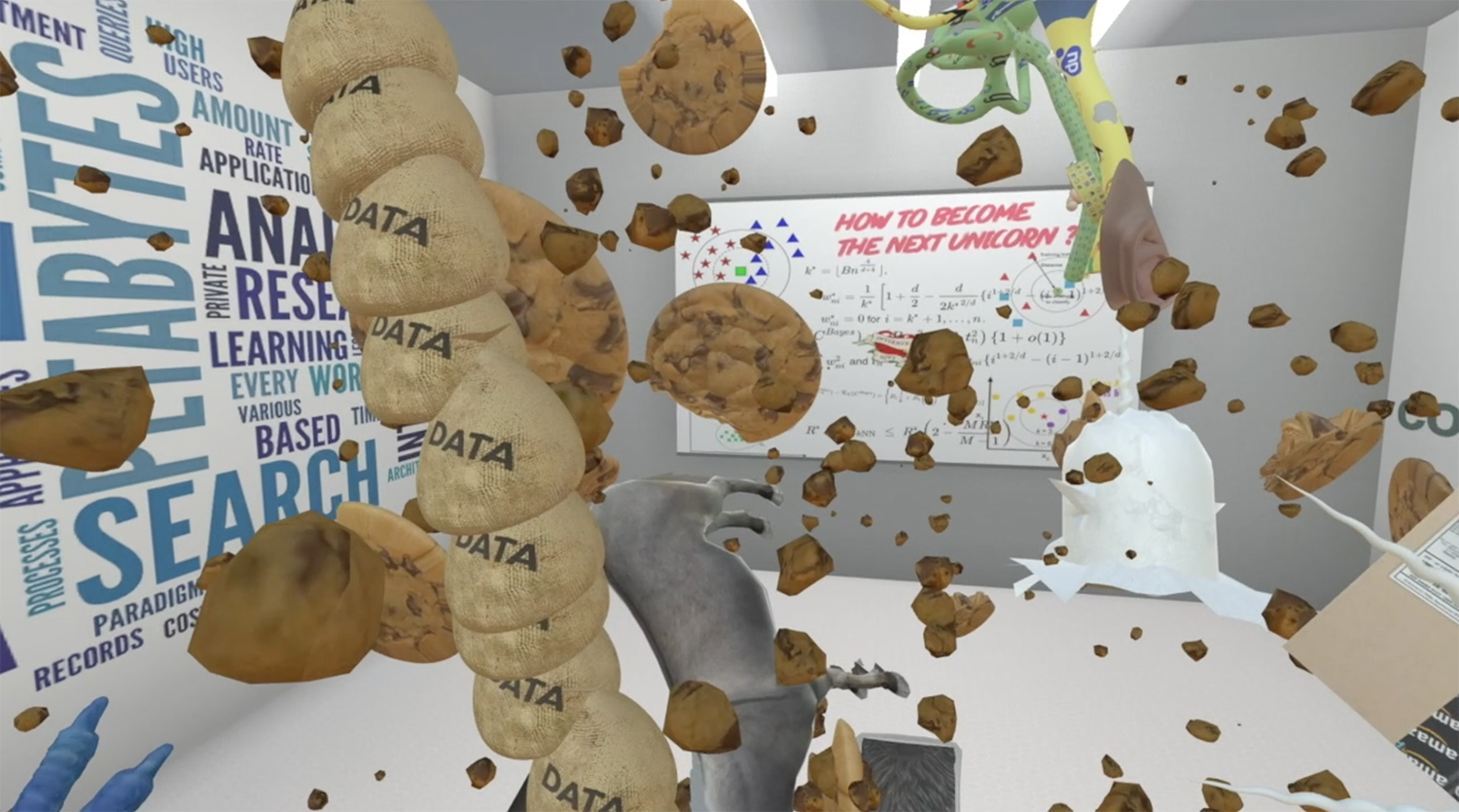

Chinternet Plus, for example, has been “on view” on the New Museum’s First Look: New Art Online initiative with Rhizome, which exhibits digital art exclusively online. Clicking onto a hyperlink on the New York museum’s website guides visitors to the work where Internet-pulled generic stock images and erratic GIFs are swiftly collaged into a catchy sequence that promotes “a counterfeit ideology”. The work is a humorous take on Internet Plus, China’s 2015 attempt to reboot the country’s declining economy through implementing cloud computing and big data into traditional industries, such as agriculture and textiles, with a five-year plan. A GIF of Shia LaBeouf diligently applauding or a stock image of a couple joyfully pulling each other’s pyjamas join a barrage of icons that Miao orchestrates to propose a branding strategy for her intentionally unclear alternative to the government’s plan.

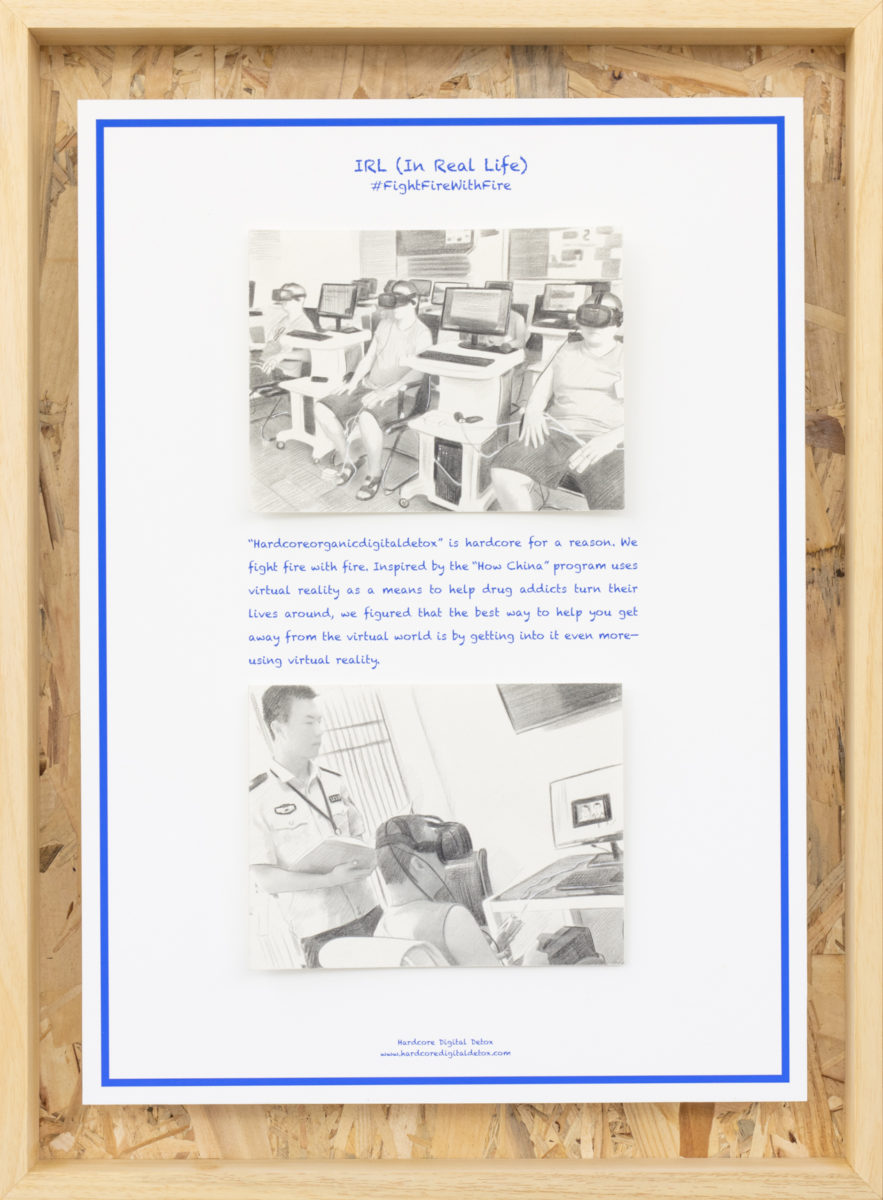

Humour is a repeating theme within a body of work that satirises a system that is inherently flawed and easy to manipulate. Her recent work Hardcore Digital Detox (2018) is the first digital piece commissioned by Hong Kong’s contemporary art museum M+ for its digital art series M+Stories, which is accessible online before the museum physically opens in the next few years. Moving through a medley of texts and images, which includes a drawing of a muscle-bound Mark Zuckerberg, viewers encounter methods of digital cleansing with motivational concepts for connecting with nature, such as rock piling or hiking. A tongue-in-cheek approach to the West’s growing trend for tech-free wellness is rendered with a DIY aesthetic that recalls early website design and marketing for mountain retreats—inviting viewers to put down their smart devices and find meaning in real-life connections.

“Self-censorship is similar to Stockholm Syndrome”

Approaching such a dark force through a comical lens is liberating for an artist whose work has increasingly become challenging to practice at her home country. “When I am in the US, I can see China more clearly because there, I am frustrated,” Miao admits, having lived between the two countries for nearly a decade. Even logging into her Gmail account in China is a laborious process which includes obtaining a VPN code. The country’s own tech giants, such as Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba, hold the monopoly over the population’s economic and social habits, growing into monstrous entities geared towards ever-larger dominance to minimise privacy and individuality.

- Miao Ying, Prototypes #2 (left); #1 (centre); #3 (right), 2018. Courtesy the artist

“There has always been a grey area to play with; however, that area is constantly getting narrower,” explains the artist, who believes the current digital-political landscape has reached new realms of horror, with an in-progress credit system to collect personal data, similar to the purchase-based credit system of online shopping platform Taobao, which grants visa-free access to Canada or Singapore for those holding the desired score. A pilot programme is currently being tested on smaller cities. The new deductive system gives each citizen 1,000 points, which drop based on their online and real-life presence, monitored through governing web companies and people observing and noting others’ public behaviours. “The plan is to have each Chinese citizen scored by 2020,” says Miao, adding that a low score will limit travel and access to certain benefits.

“Everything is about lifestyle now, and the installations promote a lifestyle that lives online”

But how did this all start? According to Miao, who comes from a generation that witnessed mass migration towards the digital realm, it all happened around 2010 in China when iPhones entered the market and a surge of knockoffs made it possible for everyone to own a smart device. Baidu had already established its alternative to Google and a new generation who would grow up assuming Google copied Baidu was learning to crawl. With access to smart devices—knockoff or real—people left the restrains of internet cafes and built their own digital realities; GIFs, which are difficult to censor because they contain a constant flow of images, have slowly become a secret code for defying censorship. Homemade pornographic or political GIFs began to roam through social media platform WeChat, while searching for the related search terms on the Internet would yield no real findings.

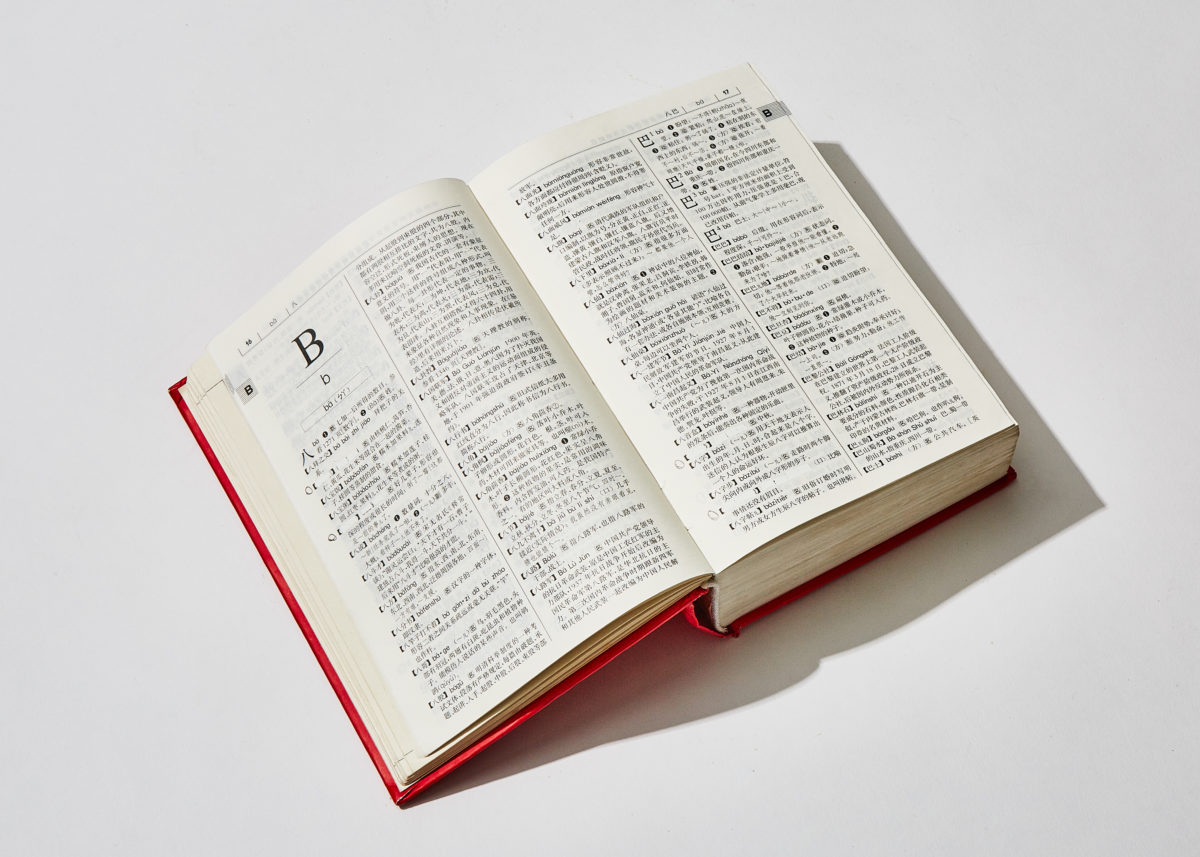

In fact, the work that launched Miao’s career stemmed from an inability to search data back in 2007 during her college years. Google had just entered the Chinese market through a censorship agreement with the government to limit access of entries deemed inappropriate, such as “people”, “communism”, “blue sky” and “penis.” She spent ten hours a day for a total of three months going through a basic 1869-page Mandarin dictionary to search the accessibility of each word on Google China, where an alert at the bottom of the page would disclaim unavailability for some of the findings, due to local laws for words that failed to pass regulations.

In those cases, she erased the word and its pronunciation with white tape within the dictionary and left its definition legible underneath, to hint at the missing content. Entitled Blind Spot (2007), this early work is a vivid manifestation of Miao’s transition from an analogue practice towards digital. Exhibited in the New Museum’s hefty online net art survey Net Art Anthology, the work was also exhibited earlier this year at the museum’s sixteen-work selection taken from the 100-artwork roster, Net Art’s Archival Poetics, which offered a cross section of works from the birth and rise of net art.

Now, spending more time in the US where her work has been garnering growing attention, Miao is among a generation of artists looking at the ways in which the digital realm limits human experience. “My work is similar to typing with gloves,” she explains lightheartedly, “the process is unconformable, but it gets you there.”

This article first appeared in Elephant Issue 41

BUY NOW