Sunil Gupta shot the portraits that make up Lovers: 10 Years On in the mid-1980s, just as the AIDs crisis was peaking in the UK. Comprised of around thirty photographs, the series was only presented once in public, as part of a group exhibition in 1984—until it was acquired by the Tate in 2018 and exhibited at Tate Modern the following year. Now it appears again, as part of Gupta’s retrospective exhibition From Here to Eternity at The Photographer’s Gallery. Gupta struggled to exhibit the series in the intervening years: “For some reason, curators found it oppressive,” he reflects.

Gupta had arrived in London from New York in 1978, following his partner at the time. In New York, his first encounters with gay culture and consciousness coincided with his discovery of photography; he was a student of Lisette Model and had taken photographs on the streets of the West Village that have since become important documents of the LGBT movement in the years that followed the Stonewall Riots.

Lovers: 10 Years On is now preserved for the public as a photo book, published by Stanley Barker.

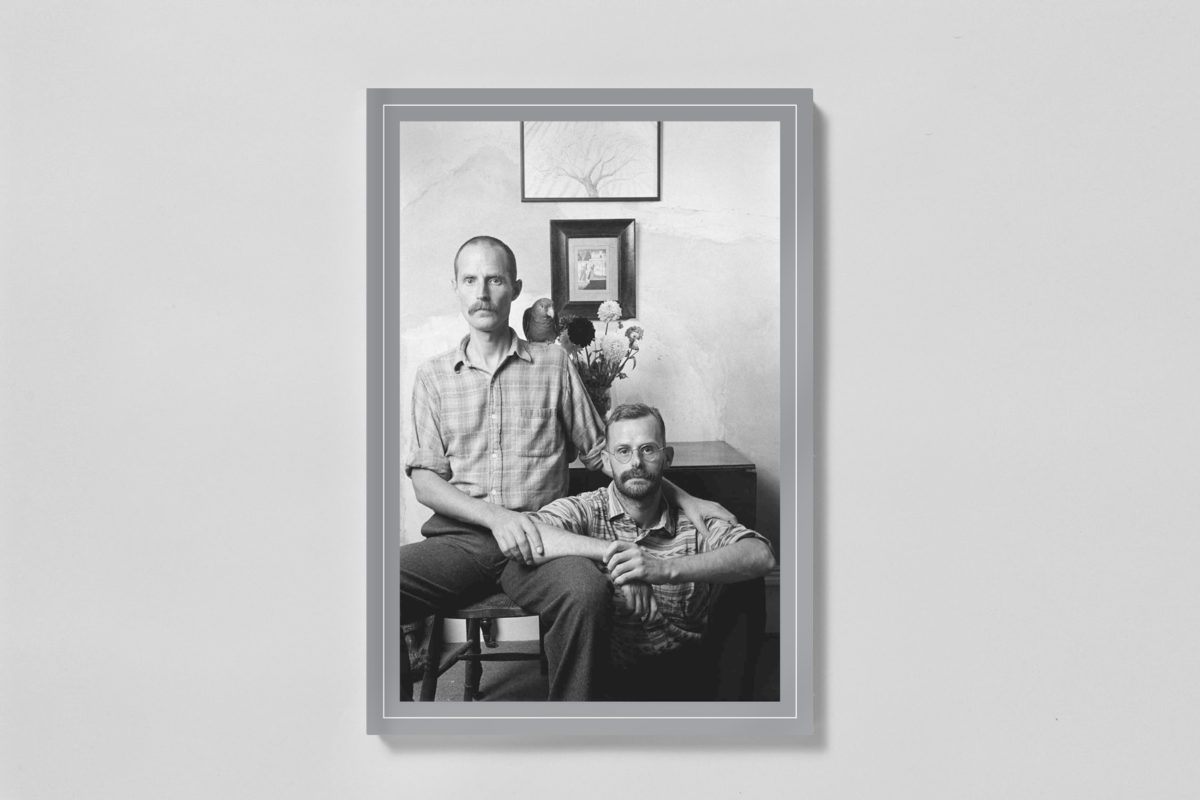

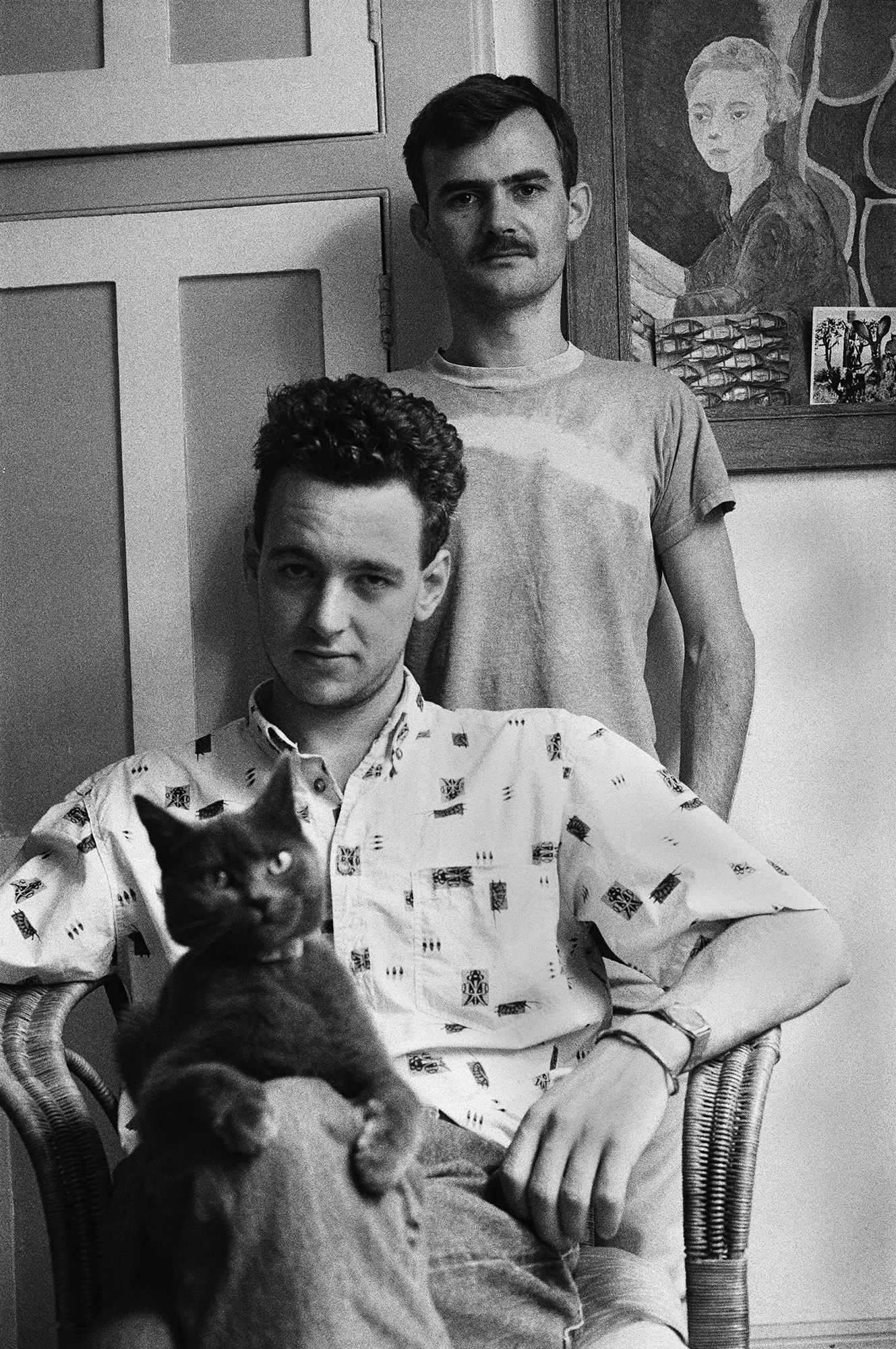

It brings together the complete original series of pictures depicting gay couples, most of them men, primarily at their homes in West London. The project began as a personal catharsis for Gupta; after moving to London Gupta’s own relationship with his lover had broken down. It had been Gupta’s first relationship and a decade long. The breakup “came as a big shock to me”, the artist has said. To make sense of what had happened, Gupta turned to the camera. “In order to meet with as many gay couples as possible, in an effort to get to know what made them tick, I set about making these portraits.” The pictures were a way to try and unlock the secrets Gupta perceived these couples must have, some recipe for success he was missing.

“These photographs represent an entirely different image from the fear-mongering British media, emphasising safety, security and monogamy”

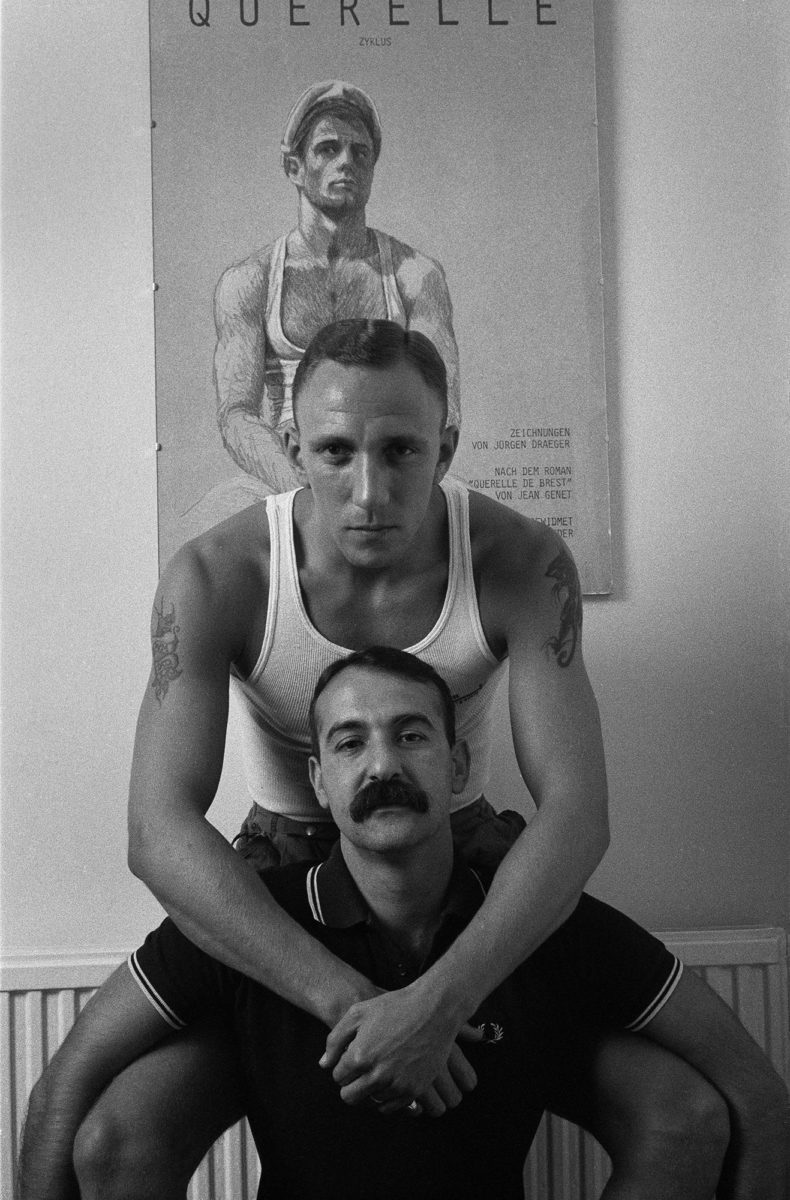

Out of this introspective journey, Gupta ended up showing gay men as they are rarely seen, during at a time that visibility was vital: by the mid-1980s the AIDs crisis had devastated the community, claiming the lives of thousands of gay men. These photographs, even though they remained between the photographer and his subject, provided solace. The fear-mongering British media at the time framed the virus as the “gay plague” and aligned gay sexuality with promiscuity, disease and death, an image that would proliferate throughout the decade. As Gupta points out, the tide of public opinion was turning against gay people despite the progress towards liberation in the west in the 1970s. These photographs represent an entirely different image, emphasising safety, security and monogamy. “Couples though had come into their own,” Gupta explains in a short text in the book. “Gay self-help groups encouraged a change in sexual behaviour and a reduction in the number of partners.”

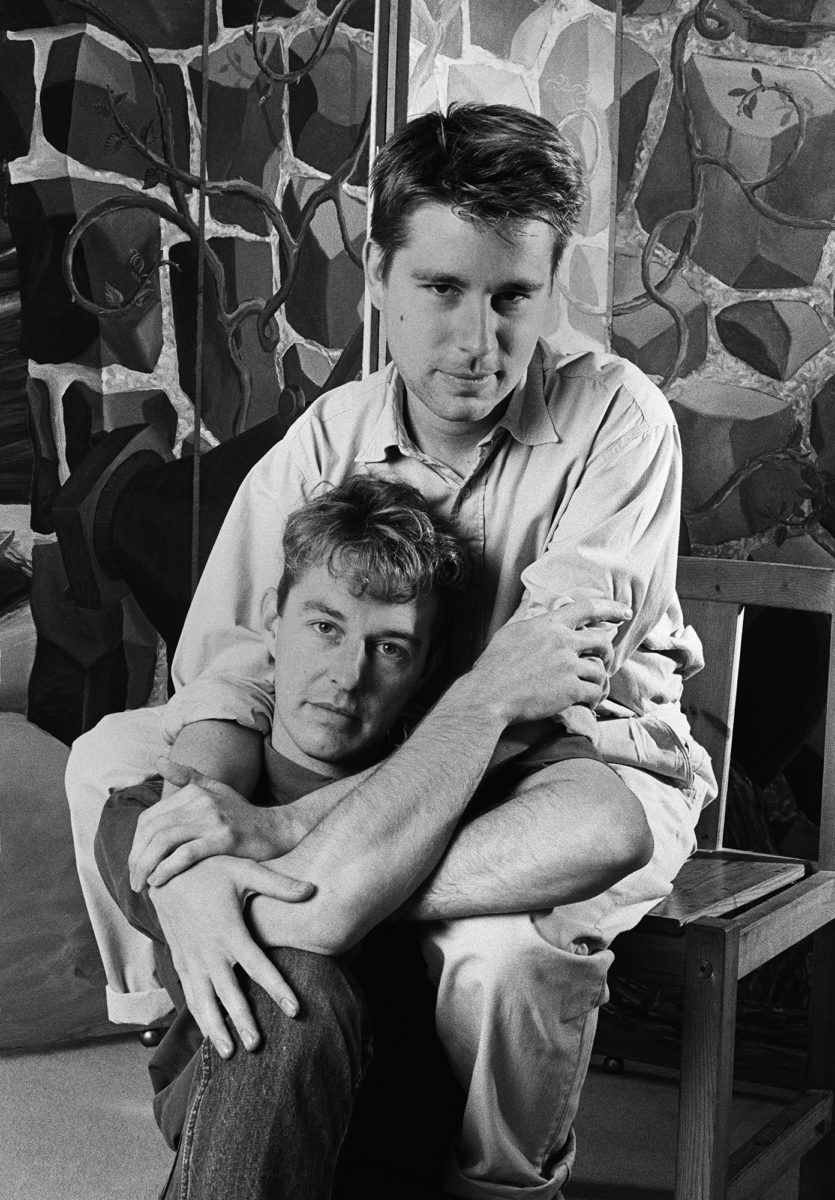

In fact, looking at the portraits today it is easy to overlook how radical this kind of representation was, and still is. There is nothing sensational, or rebellious about the pictures; the couples are presented as domestic archetypes: Roger and Steve have a cat; Ian and Julian a vase of flowers. Simon (activist and writer Simon Watney) and his partner John Paul are comfortably encircled in each other’s embrace. Compared to the amped-up, dramatic sexuality of Robert Mapplethorpe’s iconic portrait of Ken Moody and Robert Sherman, shot the same year, these are staid: neatly-dressed, white, middle-class couples in ordinary, comfortable homes, surrounded by daily domestic detritus. They are cropped close, so the space they inhabit seems made to fit only each pair and their possessions. These are the borders of their private world.

“There is nothing sensational, or rebellious about the pictures; the couples are presented as domestic archetypes”

These are quiet portraits that suggests an easy intimacy. A reflection of the everyday and humdrum life of a couple, Gupta’s subjects seem relaxed, confident and content. It is partly, perhaps, because the pictures were taken by someone they knew, who had no motive other than to get through his own grief. That’s not to say that these photographs lack the sexuality of the couple, which is subtly present, but Gupta’s interest lies elsewhere. “I believe the relationship between gay men is an important but often neglected component central to their lives,” Gupta writes of the project. The portraits do reveal something of each couple’s dynamic: gestures and gazes that are a subtle rumination on how two people of any sexual orientation negotiate power, and of what it means to share your world with someone.

It is hard to imagine what the people in these pictures must have faced outside of their own home, at a time when they still couldn’t be legally recognised as couples in the UK. Thirty years later and none of the couples, Gupta says, are still together. But the pictures remain, and they mark a moment in time that is rarely seen with such affection and tenderness.