Throughout her career, German-born, New York-based artist Andrea Geyer has employed a multidisciplinary approach (working with photography, performance, video, text, sculpture, drawing and painting) in order to critically—and often collectively—engage with the politics of time and the intersections with marginalized histories and cultural institutions. Her solo exhibition, If I Told Her, is currently on show at London’s Hales Gallery.

The central core of the exhibition stems from Geyer’s 2012-13 fellowship at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which she began an investigation into women’s contribution to the Modernist movement in the United States. Starting with the founders of the museum—Lillie P Bliss, Mary Quinn Sullivan and Abby Rockefeller—Geyer soon unearthed a vast network of women-identified philanthropists, collectors, poets, political visionaries, social organisers and activists. Intriguingly, it was a list for a dinner invitation in Abby Rockefeller’s archive that proved what Geyer had suspected all along: the social progressive movement was deeply integrated with the US’s Modernist art movement. “It was so interesting to see this composition of a dinner party,” Geyer explains. “The list included Margaret Sanger, Mary Pickford and Georgia O’Keeffe. Here they were, doing their thing, bringing people together. I started researching them, which led to an avalanche of amazing histories, documented in my map drawing: Revolt, They Said (2012-ongoing) and in the video piece Insistence (2013).”

Photo Filip Wolak, Whitney Musem of Art

Without this collaborative activity at the intersection of culture and politics, the significant shifts of Modernism would never have occurred. “You still have class and racial barriers within the groups of women, but there was a lot of collaboration and mutual support. It wasn’t relevant who somebody was, but what somebody was doing,” Geyer continues, “Everything in history happens collaboratively, but the way we are told to tell historic stories is around singular figures. If you look at the traditional biographies of women like Abby Rockefeller, they are artificially isolated. Whereas if you look at her place within Revolt they said, you can see that she was part of an incredibly vibrant scene of political, social, and cultural actors. I’m interested in insisting on these connections.”

“What this project is really doing is trying to reclaim the space that is silenced by white patriarchy.”

Despite the potential to rupture this collective amnesia or cultural erasure, ideologically motivated archival omissions have prevailed. “Bliss, Sullivan and Rockefeller had a very deep and close friendship, they would have lunch every week, and go for outings. There is not a single trace of that relationship in the Rockefeller archive. Not a note. Not one photograph of them together. I asked the head archivist responsible for the Rockefeller papers, and she said plainly, ‘relationships between three women were not considered worth archiving’.” Although these stories might be rediscovered or revisited, Geyer notes that they can disappear as quickly as they were found, particularly if the structures in which these histories are rendered invisible are not challenged. “It’s very systemic how these people are not recognised. We are trained not to recognise certain bodies as bodies of power, or knowledge, or wisdom,” says Geyer, “What this project is really doing is trying to reclaim the space that is silenced by white patriarchy.”

Geyer believes we need to open up the ways we try to understand the past. “This idea of history as being linear is a Western concept, and is incredibly arbitrary,” she continues, “There are many different cultures that believe that the past is not something that is disconnected from this moment, it runs parallel.” This history is all around us. A lot of things are right in your face, but we are so trained not to see them. The Museum of Modern Art is there on 53rd Street. It is those women’s work. Without them, it’s not there… In this broken volatile moment that we live in, all these things are rendered invisible, continuously,” she continues, “I really consider Revolt, They Said as a blueprint of how change happens. How real big social change, political, institutional change happens. The salons were so central to that, which is what the Constellation series celebrates. It’s not one star, it’s a group of a stars.”

“History was written with an active and wilful exclusion of many in mind. They wrote it in a way to continue to cut them out. That’s what I want to undo.”

The Constellation (2017) works focus on women who ran salons, gatherings, or created community spaces. They include A’Lelia Walker (who ran the most infamous salon of the Harlem Renaissance), Regina M Andrews, Gertrude Stein and Alice B Toklas, and Florine and Carrie Stettheimer, along with figures from British and European history such as Hester Thrale, the Ladies of Llangollen, Else ‘Eddy’ Klopsch and Hilde Radusch (the first lesbian to have a dedicated public monument in Berlin, instated shockingly belatedly, in 2012.)

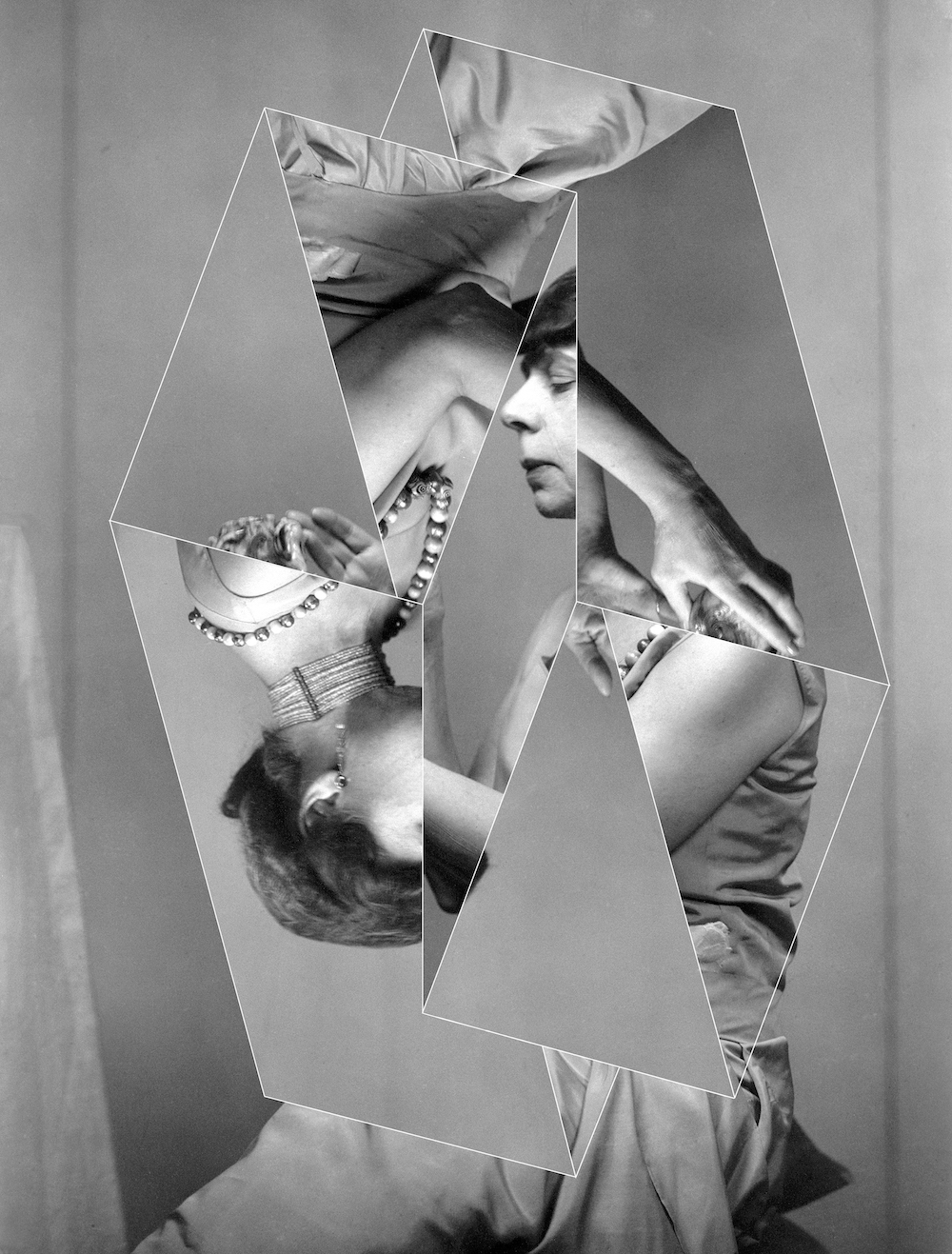

As opposed to just reproducing their portraits, Geyer has cut and fragmented the images via kaleidoscopic patterns akin to prisms. This tension between absence and presence insists on a level of interpretation from the viewer. “I wanted to show the erasure that is already part of their history,” Geyer explains, “It’s violent to cut these prints apart and rearrange them. It’s not enough to just find these women and put them back. You need to completely re-think every historical construction. History was written with an active and wilful exclusion of many in mind. They wrote it in a way to continue to cut them out. That’s what I want to undo.”

Photo: Filip Wolak, Whitney Museum of Art

Hales also presents the grainy and haptic 16mm footage from Geyer’s 2015 performance Time Tenderness at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which responded to artists “who were not white, straight, or male”. It spanned twelve different galleries within the museum. Each had it’s own vignette, and an individual script devised from various philosophical and poetic sources. “Someone described it as witches in the gallery, taking all this beautiful energy of the work, and bringing it into the space,” Geyer smiles, “we pulled the work away from it’s institutional framing.” The performance acted as both a physical and theoretical interruption.

“I feel like sometimes institutions need a ladder, either in or out of them, the people, the artworks, everything.”

The two other bodies of work on show at Hales invoke the marginalised histories of lesbian and feminist communities from the mid 1950s-1970s, from the first lesbian civil rights organisation, Daughters of Bilitis (founded in San Francisco in 1955) to a host of other activist organisations and publications that conceived new communities for lesbians and their allies. In Collective Weave (2017), logos and drawings from these magazines and flyers have been incorporated into a sequence of fabric designs. These were initially made as a backdrop for the 2017 exhibition at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where Geyer explored the legacy of the museum’s founding director Grace McCann Morley. She defines Morley as “the most important museologist of her lifetime”, but her legacy has been completely forgotten, perhaps due to the speculations that she was caught up within the ‘Lavender Scare’ of the 1950s. “I wanted to make a community for Morley in the exhibition, without having to say ‘she is a lesbian’,” Geyer notes. “I wanted to honour her privacy. The zines published by lesbian institutions created community for those who could not physically be in one room. There was information, and a feeling of belonging, and a fight against the inevitable loneliness that people had.”

Hales London, 2018. Photo: Charlie Littlewood

Each Collective Weave fabric is steam pressed and hung on hangers; “It’s an invitation to do something with them, to use them. You could have them as a bedspread, or get jumpsuit made out of them.” Similarly, in If I Told Her, a composition of three ladders adorned with horsehair are inviting yet surreal and animalistic, functioning as the Other; “You want to touch them, and be involved with them, but do you dare?” If you climb them, will you get somewhere else? Geyer’s practice is founded on the premise of being curious. If I Told Her is based on the inaugural cover of The Ladder magazine, which was published by the Daughters of Bilitis. “It had an illustration of ladder going up into the clouds,” she details. “It’s a tool to get somewhere, to do something, to change something. It’s about not being stuck. I feel like sometimes institutions need a ladder, either in or out of them, the people, the artworks, everything.”