There’s a certain time of the day, when the sun has set but the moon has not yet risen, when the sky glows a brilliant, impossible blue. It’s around this time that Andrew Pierre Hart likes to start painting: a lucid, generative time beyond the enforced productivity of the nine-to-five workday. Building layers upon layers of colour (lapis, nocturnal indigo, ultramarine, electric violet) in rich, velvety swathes, Hart’s canvases hang on the wall like dense slabs of night sky.

The artist’s recent showing at Frieze Art Fair in London with Tiwani Contemporary drew acclaim from critics and punters alike, and his painted works quickly sold out. “Purple is a healing colour,” he tells me in his London studio. “When I thought about Frieze, and the amount of people working there and walking through, I liked the idea that they might be able to get a ten-second healing from passing the booth. I hope my work gives people somewhere to go.”

Healing is important to Hart, whose practice seeks to materialise a unified theory of sound and vision in symbiosis. Prior to studying painting, he ran Deepart, a record label specialising in experimental electronic music and Detroit-style techno. Later, at the Royal College of Art, he developed a theory of ‘Sonic Ordering’: an underlying and ever-present sonic architecture at the baseline of perception. “There was a photocopier at the RCA that had a hip-hop beat,” he says. “91bpm.”

Also a musician and producer, Hart frequently hand carves wooden sound systems from which to play his tracks and playlists: boxy speakers made up of undulating layers of ply, like big sound frozen mid-vibration.

In the artist’s paintings, marks are applied rhythmically or “played into the surface”, forming not just a response to sound but a kind of loose graphic score. Music listened to in the creative process seeps into his compositions by “osmosis”. “You can’t have one without the other,” he says, comparing his work across disciplines to the integral role sound plays in film. He wonders, what would Jaws be without music? “That’s a plastic shark!”

“The way we reward what we consider to be intelligence leaves out the many more complicated things at play”

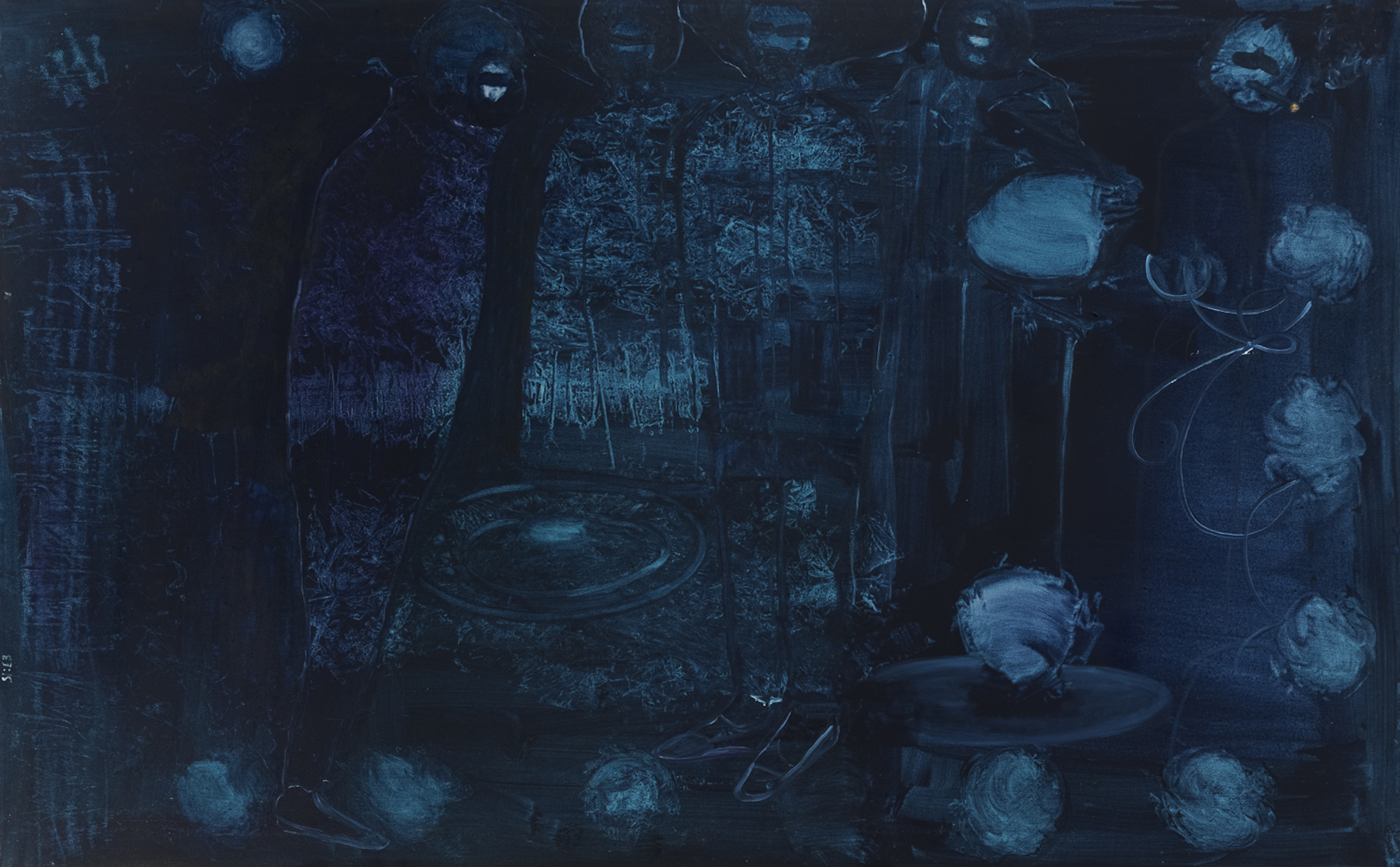

The oceanic expanses of the Roho (a speculative cosmos depicted in Hart’s paintings) are charged with a decidedly sonic lifeforce, its inhabitants the keepers of a potent and fugitive knowledge. Sound, for the people of the Roho, is the remedy, a salve for a damaged world.

“I’m invoking them to speak to me,” he explains of the nebulous figures who populate his canvases, garbed in sunglasses, robes, and the occasional statement shoe. Hart is careful not to deem these portraits or narrative paintings. Rather, they are born from an improvisatory approach: “clouds I can pull from… a story that is continually writing itself.”

In The Listening Sweet (2020), a composition of oil and charcoal for which Hart’s 2021 solo exhibition at Tiwani Contemporary was named, two such silhouettes appear to congeal out of the painting’s inky darkness, bruised shadows. Although they are near life-sized, the pair’s faces are obscured, angled towards each other in a conspiratorial glance. It is clear that they know something we don’t.

Sunrise/Sunset Over Ladosian (Bass Experiment) (2021) sees a small crowd gathered around an audio set-up emerging from the murky terrain at their feet: rocks; the round diaphragms of speakers; a laptop placed so that its glowing screen faces the viewer, revealing the jagged lines of an audio editing software. There is something of the ritual about this assembly, a lurid seam of amber sky breaking over the distant horizon like a shock.

“It’s definitely about questioning history. It’s definitely questioning who set the rules. There are no rules, are there?”

It is not uncommon for Hart’s topographies to find themselves ruptured by some remote split or puncture. The two figures of Sonara & Blacqousti (2021), currently on show at the Hayward Gallery’s Mixing It Up: Painting Today, stand before a craggy breach in the composition’s blue-black surface, a sort of cave mouth gushing bright cerulean liquid. Such openings appear not as threats, but portals, entry points or secret passages through which these beings might steal away or viewers might be admitted in.

Sonara and Blacqousti are, for Hart, newly “imagined deities of Black contemporary music”. “There aren’t very many, so I created my own,” he recently explained in conversation with Alexandria Smith, head of painting at the RCA and co-organiser of the collective Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter. Within the artist’s contemporary sonic mythology, noise contains unspeakable power: specific frequencies (when channelled in the right direction) can remedy ailments of the body, music’s vibrations can be harnessed to unlock the potential of flight.

This is all rooted in reality, Hart believes. He tells me how listening to all 18-odd minutes of Miles Davis’ Guinnevere can apparently cure a headache, and how scientists are currently working with sound waves at 22kHz to levitate small objects in order to study the pharmaceutical effectiveness of certain medications.

Real scientists, too, figure among the Roho’s pantheon of innovators. At Frieze, the trailblazing Black female inventor Valerie Thomas holds aloft her 1978 creation, the illusion transmitter, in the central panel of a sizeable triptych (a format favoured by Hart for its allusion to the DJ technology of the turntable and mixing deck, with two speakers flanking a mixer). Combining two concave mirrors and strategically directed rays of light to produce optical illusions similar to holograms, the device was used by NASA and directly impacted 3D modelling technologies used in the health and entertainment industries today.

“I liked the idea that people at Frieze might be able to get a ten-second healing from passing the booth”

“Sound experimentation is a very male-dominated environment, so within my work I try to address that imbalance or question some of those positions,” Hart explains. “The female figures tend to be the conductors of the experiment.” His practice makes it clear that change is not so much about inclusion as it is about fundamental re-composition, in terms of process, education and form. “It’s definitely about questioning history,” he says of his methodology. “It’s definitely questioning who set the rules. There are no rules, are there?”

While Hart considers himself a self-taught artist (“I did my BA in my thirties, so all of my grounding was before going to art school—I learned from books on Edo painting, Japanese painting, Chinese painting, in Swiss Cottage Library”) that hasn’t stopped him returning to the RCA just two years after graduating, this time as an educator. “The way we reward what we consider to be intelligence leaves out the many more complicated things at play,” he muses.

His “improvisatory alternative Art School for the moment,” instituted during a Spring 2021 residency at Beaconsfield Gallery Vauxhall, saw one-on-one exchanges with musicians, dancers, and fellow artists, from Shabaka Hutchings and Tic Zogson to Serena Huang and Kanika Carr, prioritising “rhythmic research” and collaboration as a way of envisioning an alternative, cross-modal pedagogy for the future, one based around listening.

“Rather than just hear each other, we need to listen to each other,” concludes Hart. “That’s what it all boils down to.”

Chloe Carroll is a curator, writer and researcher based in London

Images courtesy the artist and Tiwani contemporary