After seven months spent in lockdown, attending overstuffed exhibition openings—where little art is seen, and many forgettable conversations are had—is something of a distant memory. But as the art world ditches online viewing rooms and stretches tentatively back into its physical skin, how much of its conventional operating logic is now obsolete? What new and alternative kinds of exhibition experiences can be prototyped?

These questions are at the heart of Andy Holden’s current solo show, The Structure of Feeling (A Ghost Train Ride), at Block336, an artist-run project space in South London. Originally scheduled to open in March, just as the UK entered lockdown, the show sat in suspense like a cartoon reliquary. When it finally opened in mid-September, it was reworked from the ground-up to fit an entirely new set of social constraints and conceptual possibilities. “While redesigning the show, there was this constant question,” says Holden. “What can we do now when the stakes are much higher in terms of asking someone to go see an exhibition?”

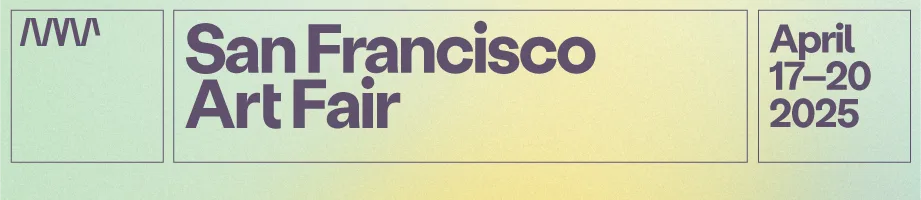

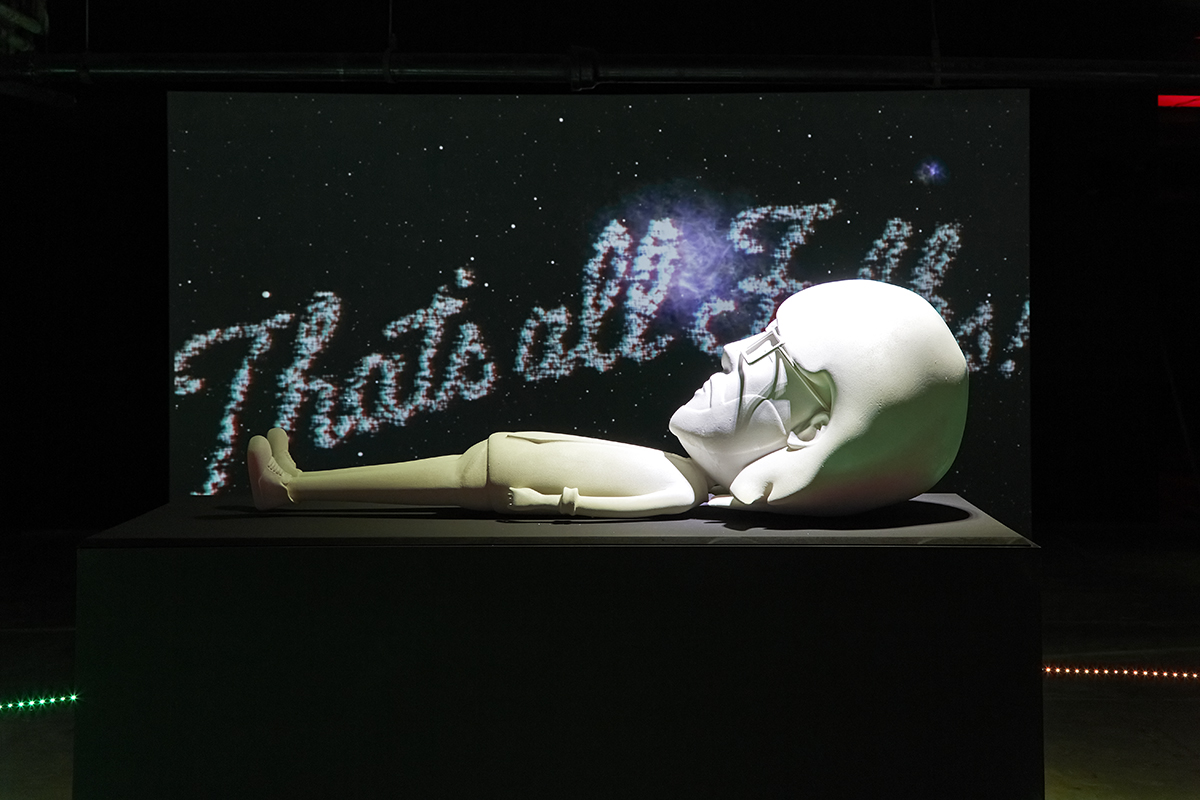

Billed as a “ghost train that guides visitors through a desolate post-cartoon landscape,” the exhibition eschews a crowded gallery get-up for a low-density experience that’s as hands-on as it gets in the age of Covid-19. Four pimped out mobility scooters, departing once every 45 minutes, are the mythological chariots that funnel visitors through Holden’s woozy mixed-media world.

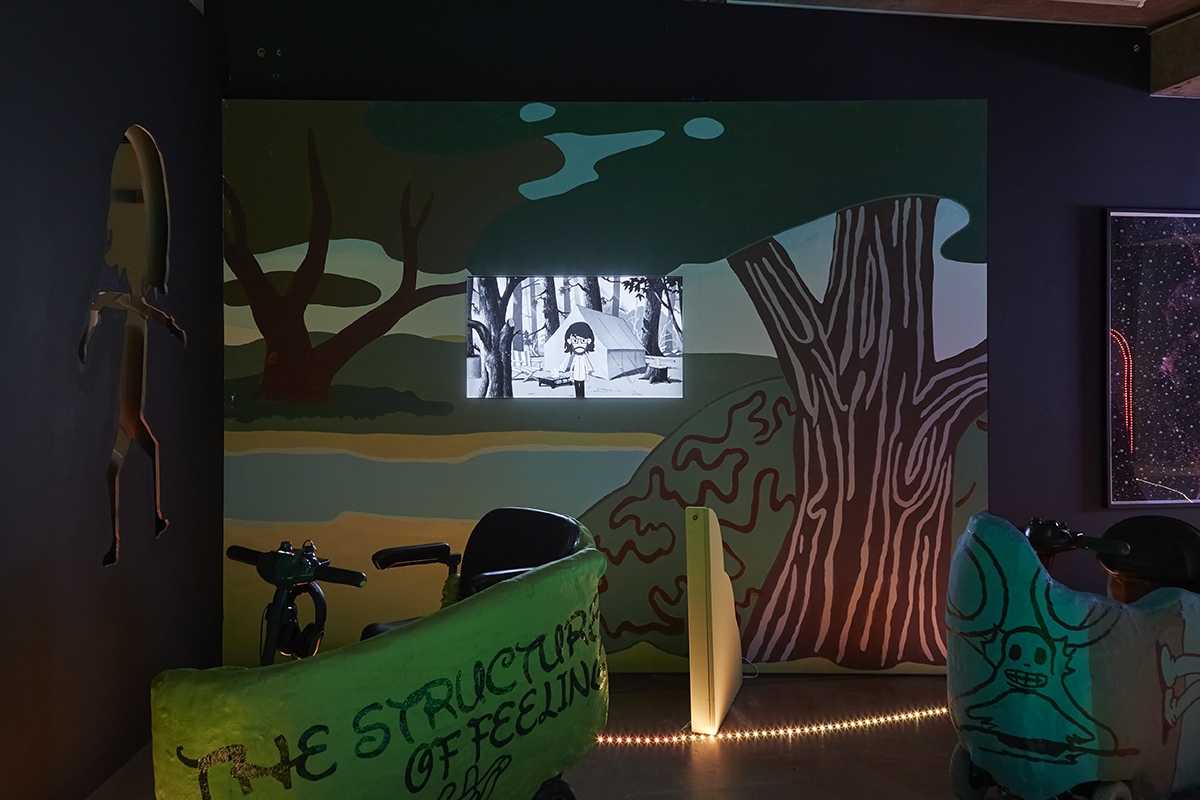

Anchored around a series of five short videos produced over the last four years, the exhibition, located in a LED-lit, cavernous concrete basement, dilates to include totemic candy-coloured sculptures, cosmic prints and supersized emulsion landscape paintings soaked with nostalgia. Scooting up to each video screen, visitors plug in their headphones or don their 3D glasses for a strung-out existential joyride through Holden’s cartoonish consciousness.

“Four pimped out mobility scooters are the mythological chariots that funnel visitors through Holden’s woozy mixed-media world”

“It’s flippant but with feeling,” says Holden of his latest body of work. Departing from Laws of Motion in a Cartoon Landscape (2011-2017), a film where Holden makes the case that we live in a cartoon world and should heed their absurdist physics to better navigate our own reality, Cartoon Shorts (2016-2020) is something of a pivot. Following the tracks of Disney, which in 1965 responded to the slow death of American animation’s golden age by opening World Disney Resort, a theme park and entertainment complex in Florida, Holden here too folds cartoons into an immersive experience.

Similar to the Disney Resort’s kaleidoscopic utopia that featured a Fantasyland, Frontierland, Tomorrowland, and a Main Street USA amongst its garishly themed architecture, Holden’s exhibition at Block336 leads visitors through a variety of cartoon landscapes: from a Roadrunner-inspired desert, to a psychedelic forest, haunted house, and finally, a post-apocalyptic city. Each realm is infused with philosophical and psychological ruminations: from Sigmund Freud and Karl Marx to snippets of poetry from William Wordsworth’s Lake District wanderings.

Holden’s cartoon avatar appears superimposed atop these washed-out landscapes, aware of their artifice but unable to escape them. Feelings of melancholy and entrapment are tangible. Like the avatars who cannot touch the walls of the gallery nor step out of their chariots, visitors experience a shared sense of dislocation.

Yet as clickbait Buzzfeed headlines appear on desert horizons, and cat memes manifest like post-internet glitches on abandoned city skylines, that alienation melts into wry comedy, and at times, a kind of lightness. A supersized CNC milled cartoon sepulchre of the artist adds to the general mood of comic melancholia. This absurdist delight dilates in-between film viewings, when you’re reminded of the strangeness of your situation: careering around on a fibreglass-encrusted scooter that routinely dies or sends you zooming deeper into Holden’s cartoon void.

“People find an element of the dystopian in Disneyland, but it isn’t really there,” suggests Holden of the tendency for his exhibition to be read as all doom and gloom. “It’s not meant to be an inverted Disneyland by any means. It holds a lot of the joy of those spaces, where the communing, the giving over of the body to a new experience is paramount. Maybe that’s where [the exhibition’s] optimism lies.”

The necessity of making space for these new experiences also stems from the exhibition’s conceptual namesake: Marxist theorist Raymond Williams’s concept of the ‘structure of feeling’, as laid out in his 1977 book of the same title. Williams campaigned for a kind of unsticking of history through feeling; by exploring the ‘consciousness of aspirations and possibilities’ of the past, he believed, we might arrive at a different understanding of the present. Ditching traditional valuations of culture as a reified object, it could instead become an emotionally intuited, highly social, and eternally fluctuating entity rooted in lived experience.

More than just an opportunity to experience post-pandemic art in a joyful way, The Structure of Feeling challenges the dominant operating logic of the art world by proposing an alternative rooted in accessibility and accountability. It questions how and why we turn out in search of entertainment and enlightenment, and in what numbers. It asks whether certain staples and taboos of exhibition-organising, such as the mandatory garlanded opening and closing nights, where, Holden says, “everyone comes first and has a terrible experience viewing the art”, are valid attitudes for both organisers and attendees to hold in 2020.

“As cat memes manifest like post-internet glitches on abandoned city skylines, alienation melts into wry comedy”

Holden’s exhibition works against the bottlenecking by spreading out visits to four per slot, averaging around 50 visitors per day. The post-pandemic viewing experience is democratised: each visitor sees the work within the same window of time and at the same pace. Like all exhibitions held physically at this time, there is a new form of accountability on the part of visitors, who must register for a designated slot and show up on time if they want to see the show. Likewise, the shadowy figure of the exhibition attendant, conventionally scrubbed out of the picture by institutional hierarchies, here becomes a vital agent in managing the flow of visitors and sanitising the exhibition between slots.

“At the moment there are no set rhythms, both in art and on a much larger scale,” explains Holden. “A lot of people aren’t working—they may have lost their jobs in the pandemic—or are questioning who and what they’re working for, because everything is in flux.” If the art world is to survive this pandemic, it has to bend into thinking through alternative value systems and uses of space, time, meaning and experience. Holden’s ghost train is a funny, heartbreaking and generative point of departure into the wild ride of an uncertain future.

All images courtesy Andy Holden and Block 336