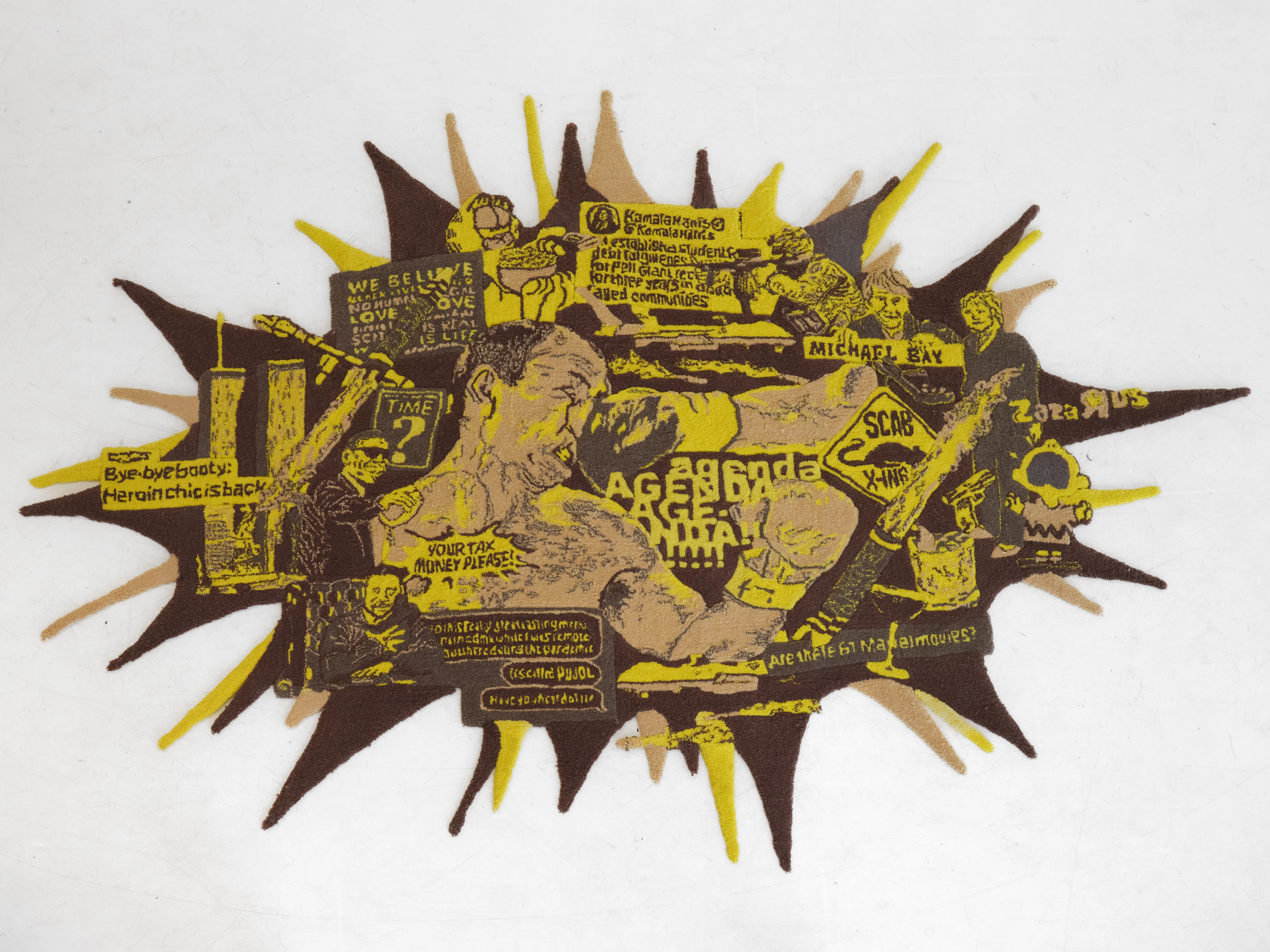

Agenda Agenda Agenda!!! The piercing, tufted words scream from underneath an outstretched boxing glove, punching a man in the face. Garfield, the cat, sits above eating popcorn, loafing, and staring disinterestedly into a Kamala Harris tweet about student loan forgiveness and a Pell Grant for three years in disadvantaged communities. A black-ops soldier and his scoped assault rifle peeks out from behind it. Michael Bay is there too, as well as the Twin Towers, Hilary Clinton, and a text bubble that reads: “Bye-bye booty: Heroin Chic is back.” A caption responds from beneath the chaos: I went to this great tasting menu restaurant with natural wine while I was working remotely in CDMX during the pandemic. It’s called PUJOL. Have you heard of it?” Somehow, they all feel at home in Los Angeles artist Angela Anh Nguyen’s Agenda, AGENDA, AGENDA!!!!!, a 15 x 7.5 ft rug.

Nguyen’s textile practice is unavoidably unique. Her pieces are intricately made, conceptually dense, and have appeared at galleries and art fairs across the country, yet they also are functional rugs. In this way they hold a value different from that of a painting, a sculpture, a video, or a print. There is a subtle questioning embedded in their nature: why do we devalue art with a practical function?

Like most aspects of commerce, textile production underwent a rapid change during the Industrial Revolution. The techno-innovations of the period, such as the picker, the carding machine, and the combing machine, made the textile economy one of the most lucrative industries in the world. They also brought what was once considered a practice of the home into an industrial space and, subsequently, into the realm of mechanisation. Since this period, the textile form and the commodity form have become generally synonymous with one another in the Western imaginary, an association that can be felt palpably in the art context, where the work of textile artists has often, historically, been segregated into the arena of “craft.” This subsequent segregation and its recent semi-unravelling has been discussed at length. I bring it up not to harp on it but to establish a kind of clever and subversive synthesis Nguyen conjures through her work.

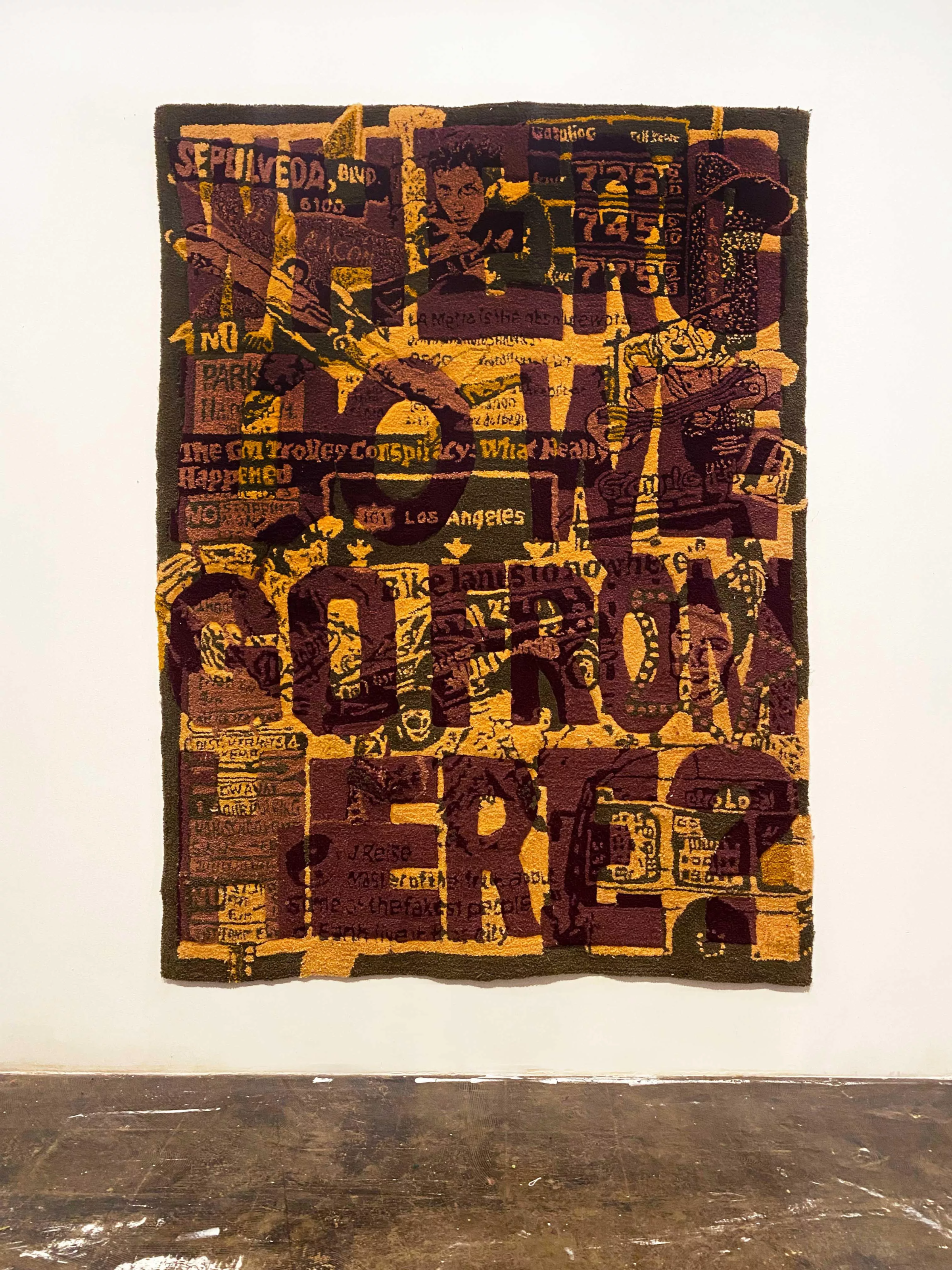

Nguyen’s practice does not run from the history of commerce that surrounds her medium. Her style embraces its historic relationship to the neoliberal mechanisation that has defined it for so long and then turns it on its head. Utilising juxtaposed cultural iconography, Nguyen’s pieces toil with the debris of mass culture using a method that predates it: tufting. In this way, they serve as the imagistic maps to the collective unconscious of a particular social topic/issue, accentuated by the inherent criticism embedded within their medium. “A lot of people who are taking up tufting are re-creating luxury goods, which I find really awesome, mainly because of self-agency and affordability,” Nguyen explained to me over email. “I’ve been seeing a lot of off-white rug re-creations being made that say “rug” or whatever. It’s sick because the act is sort of like a meta using-the-tool-of-production-to-resist-against-the-system-of-production type of thing. At the end of the day, people want agency, in both our political economy that exploits us, and in our lives outside of that (if at all possible), such as recreational pastimes, like creating art.”

The artist’s rugs are as complex as they are hilarious. There’s an irreverent humour that flows through them, one that is pointed of the moment in that it is often rooted in an underlying, desperately serious inquiry. The cultural signifiers that compose her pieces are enmeshed in a way that conjures an unconscious interrogation in the mind of the viewer. Such an interrogation’s natural conclusion, the coveted “Ah-hah” moment, is quite common, for me atleast, when attempting to figure out what Nguyen is getting at. Her pieces are kind of like inside jokes for all those subjected to the painfully absurd state of our discourse.

In Nguyen’s piece titled “Drone,” images of war surround a tufted drone with a meme in the middle that reads: “What’s your biggest ick?” War is indeed one of mine, and hopefully, many people’s (at least they think it is,) but the apparent juxtaposition brought about by its presence in the piece dissolves into the realisation of relation. Through weaving “What’s your biggest ick?” into the structure of the drone itself, the piece becomes involved in a conversation about the role social media at large plays in structures of violence and war.

I first encountered Nguyen’s work on the internet, which feels apt. Mimetic density is part of what gives Nguyen’s work such biting resonance in the digital age. While her practice has material resonance and aura in its rug- form, her pieces are also inherently related to the digital archive through their irrevocable ties to the internet’s chaotic, imagistic language. “I enjoy collaging, and I love density. I love saturating the viewers with information, both real and fake, so they’re able to draw their own conclusions. As we live in an era of misinformation, I like to use that as a motivating factor to encourage some sort of doubt in the viewer,” Nguyen said. “Maybe that’s manipulative, or maybe it is telling of the times we live in? To encourage some sort of critical thinking, not like it is my duty to do so, you can think as little or as much as you want.”

In a sense, Nguyen’s work physicalises the presence of digital culture in the material world and, at a functional level, brings it into the home, a space which, through the phone, is losing its sacred separation from the rest of the world. “My work is also a documentation of the culture of “doomscolling,” she says. “We’re on our phones all the time, always saving memes, taking screenshots, that’s all that is: a reflection of the times.”

Written by Theo Meranze