Cinemas are always empty in the summer. When the sun is out, days are better spent lounging in the park than in a darkened room and, besides, is there anything as pitiful as the summer release? Currently playing in cinemas near me: Ant-Man and the Wasp, Sherlock Gnomes and yet another instalment from the Mission Impossible franchise. Don’t get me started on THAT feel-good film of the summer and, yes, I do know that the cast did their own singing for it.

On a warm night, though, there’s nothing better than throwing open all the windows and putting on a film. With no risk of FOMO at the cinema, now is the best time to watch definitive flicks that make you actually feel something, that change the way that you see and that shake you out of your everyday and your ordinary; movies that make you want to stick your head out of the window and shout, “I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore,” as the iconic line in Sidney Lumet’s satirical Network (1976) goes—recently vividly reprised at London’s National Theatre by none other than Bryan Cranston.

The powerful allure of the big screen is its ability to reflect reality through a slightly altered lens, close enough to our own concerns to invite self-examination and yet distant enough to build compassion for others. Directors through the decades have had the conviction and vision to incite real-life action, and it is the angstiest films that get us mad enough to do something about it. Whether they offer reminiscences on failed relationships or an insight into bourgeois frustrations, they tug at buried anxieties and reveal the rage in each of us.

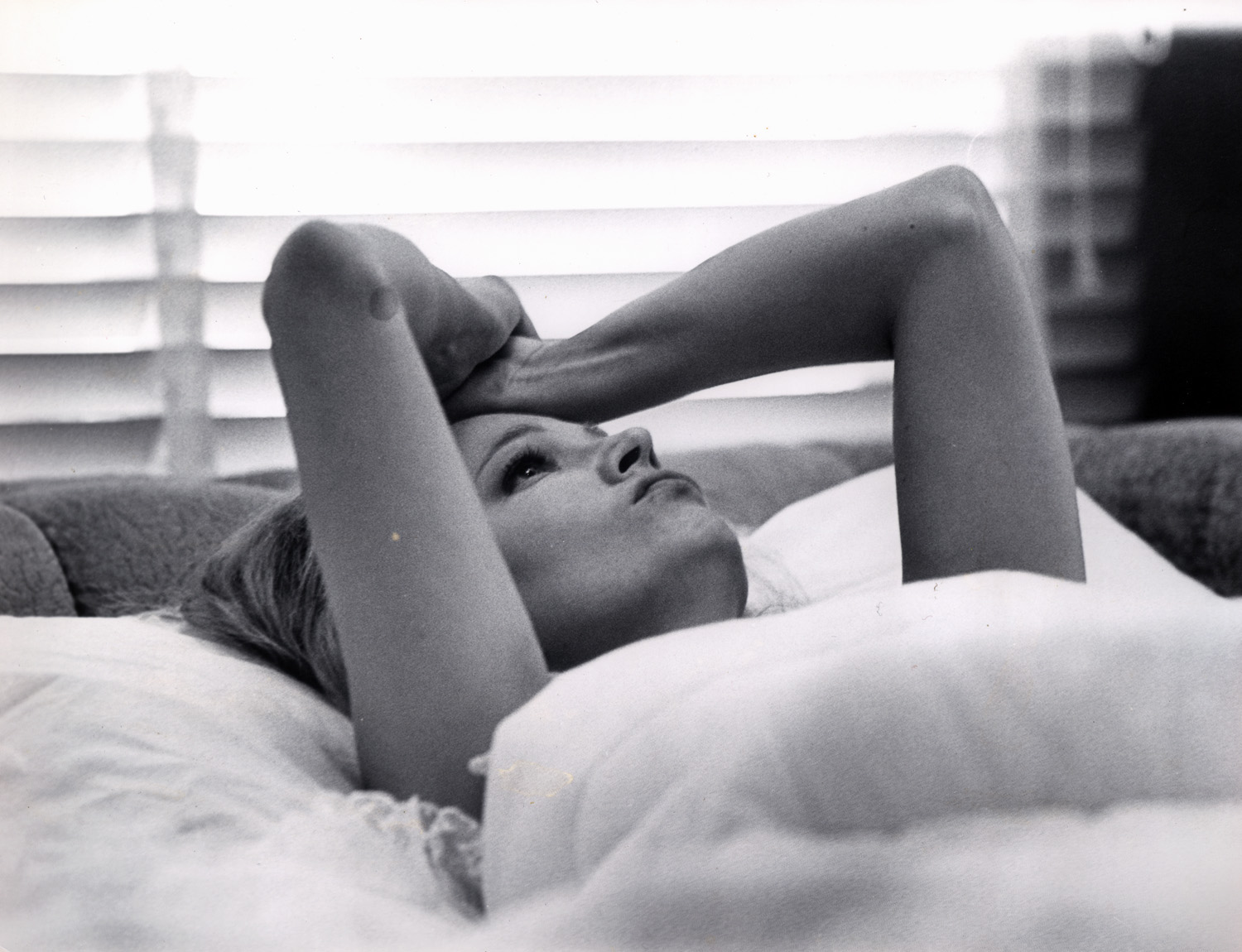

Hiroshima Mon Amour, Alain Resnais, 1959

Alain Resnais is surely the undisputed master of capturing the fleeting, disruptive effects and tricks of memory on screen. Hiroshima Mon Amour, a classic from early in his career, traces the reflections of a nameless French-Japanese couple as they look back upon their brief relationship—and earned screenwriter Marguerite Duras an Oscar. Their painful conversations move seamlessly between personal and political, set against the backdrop of the recent atomic bombing atrocity of Hiroshima. “I meet you. I remember you. Who are you? You’re destroying me. You’re good for me,” they proclaim, encapsulating the indecision that can both paralyse and exhilarate in love.

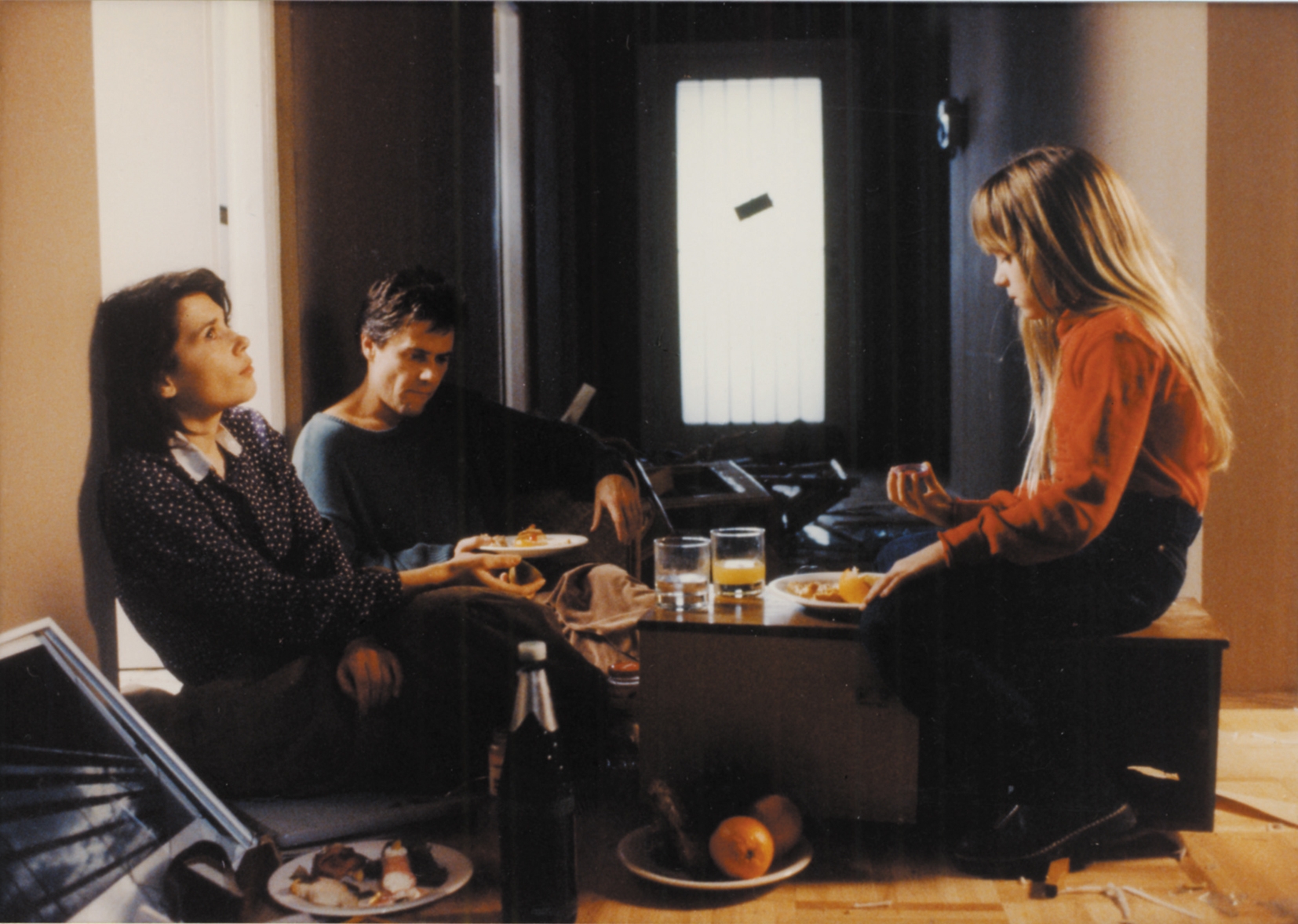

La Notte, Michelangelo Antonioni, 1961

Love is all-but absent in Antonioni’s brilliant exercise in social observation, focused on a day in the life of an unhappy married couple, and yet it remains the central theme of a film that relentlessly picks apart the minutiae of romantic relationships. The wealthy, bored couple, played by Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau, drift towards infidelity at a party but find themselves forced to face their deteriorating respect not only for one another but for themselves. The worst realization of all is that they are beyond caring about each other, unable to summon up lust, anger or even hatred. This is angst at its most hopeless and despairing.

A Woman Under the Influence, John Cassavetes, 1974

It takes an actress with the remarkable abilities of Gena Rowlands (Cassavetes’s real-life wife) to fully embody the mood swings and personal insults suffered by Mabel, the memorable protagonist of A Woman Under the Influence. In this devastating film she offers surely one of the most sensitive depictions of mental illness ever shown on screen, revealing the pressures on women to perform within the narrow constraints of family and the home. Most remarkable is the film’s searing portrayal of the good times as well as the bad, the highs before the lows and the endless struggle to achieve a balance amidst the two extremities.

The Seventh Continent, Michael Haneke, 1989

A selection of angst-ridden films would surely be incomplete without Michael Haneke, who has built his name on menacing films that are frequently rooted in moments of violence. These violent episodes are often implied rather than shown on screen, sowing subtle seeds of terror in the imagination to greater and more horrifying effect. In The Seventh Continent, his first film, all the classic Haneke tropes are gloriously present, from brooding middle-class family to a suitably bleak ending, turning upside down everything that you’ve ever aspired to.

Mike Leigh is another name it would be amiss to omit, with his acute take on the grim underbelly of British life. Johnny is his tragi-comic protagonist in Naked, a drifter with something to say, shooting his mouth off to anyone who will listen, with wacky takes on everything from the evolution of the world to current affairs—and a whole lot of pent-up rage. Much of the film’s singular dialogue was built on improvisation, and it paints a raw portrait of east London as Johnny leads a self-effacing path of destruction, from aggressive sexual conquests to street brawls.

Dogtooth, Yorgos Lanthimos, 2009

To be held captive does not always require physical restraints, as Dogtooth chillingly demonstrates with the tale of a controlling father and his two daughters and son. The family live in a seemingly ordinary middle-class Greek home, but the adult children are not permitted to leave the parameters of their household. Instead, they are taught a twisted view of the world, one in which cats are violent monsters to be feared and sexual favours can be bartered for trinkets and video tapes. The film is surreal, darkly comic and disturbing at turns, questioning the systems of belief that we each learn and uphold.

The Work, Gethin Aldous and Jairus McLeary, 2017

A different type of claustrophobia sets in onscreen in The Work, the extraordinary documentary filmed almost entirely inside a single room at Folsom Prison. Over the course of four days, convicts take part in a unique group therapy retreat where they meet men from outside the prison and together delve into past experiences to overcome deep-seated anxieties and past traumas. The resulting outbursts are as raw as they are revealing, with physical and emotional “work” that shows the impact that both anger and compassion can have when tackling your past and taking hold of your future. This is a film filled with angst but which arrives at a transformative moment of redemption that is challenging, revelatory and utterly compelling.