Queens, New York – When I arrive at Park’s studio, I’m led to a charcoal coated room, void of colour, housing the occasional cluster of Diet Coke cans and the whisper of New York’s beloved 97.1 FM.

Park’s work, exclusively grayscale, lends itself to iconic comic imagery one might see on a curated, vintage, Americana-core Pinterest board. Pinterest is just one cyber-alley where Park sources reference images — if you hover around her studio long enough, you’ll find plenty of her b&w photo-collages peeking out from under miscellaneous piles.

“My idea of America is misimagined,” Park admits in front of a large painting with the word, “Daddy” tagged across. Born in South Korea, Park’s family bounced around a few continents before finally settling down for her formative years in the fine state of Utah. During our chat, she reminisces on her life B.A. (Before America), when the country was just a figment of the flashing lights behind Hollywood.

The allure of American media outlets, celebrity gossip, billboard advertisements, television commercials, movie trailers, and so on, would all influence the fabricated world that unravels onto paper in Anna Park’s studio.

An “American Dream” muse didn’t click randomly, Park recalls living with vivid awareness of it growing up and watching her mom pack up their whole life to move to the States. When she finally settled into the Land of the Free and Home of the Brave, Anna realised there was very little truth to the media she’d been absorbing — Park’s practice dissects this fallacy and its dark underbelly.

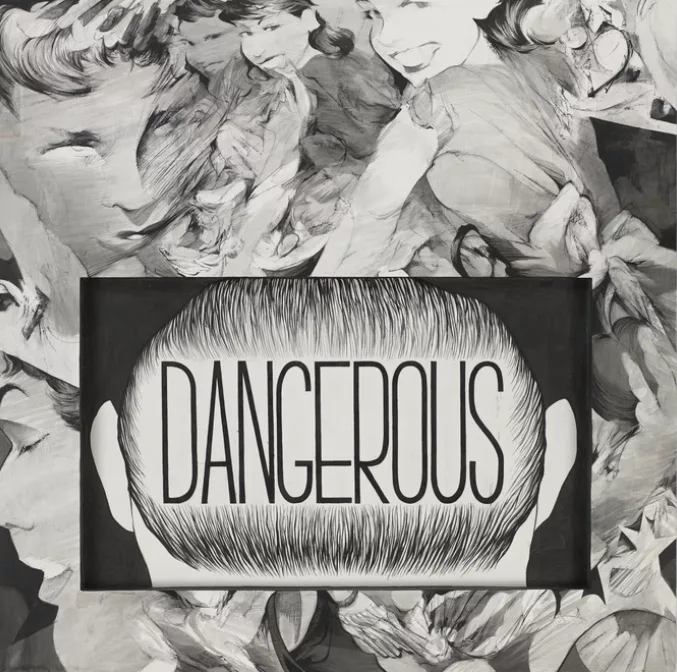

Park’s first international solo museum show, Look, look.,opened Saturday, April 20th at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. The show champions a technique in which Park employs foam substrate over board, building dimensional windows around a duotone world. The titles of Anna’s shows and individual artworks are classically conversational. Park confesses naming her exhibitions is one the hardest parts in preparing for a show, level to coming up with a cheeky joke. In naming this particular show, Park was inspired by a children’s book which featured illustrations of kids doing innocuous things. In one drawing, a child points and exclaims to the other, “Look, look.” The simple naivety of the children and possibility of interchangeable punctuation, raised the question of language and interpretation. How does one navigate the ambiguity and insider secrets of American vernacular within all forms of media? The repeated four-letter word literally calls us to evaluate.

American tropes in Park’s work are satorised and seductive, poking fun at the scrumptious dreams that consumerism has to offer. Most of her paintings build a liminal space just tangible enough to place yourself, yet, allusive to the era in which it lives. The language and typeface leans contemporary, while the colourless imagery draws on vintage nostalgia. Viewers are left with a sense of evergreen Americana, something distorted and timeless. Grasping for a chronology, I can’t help but notice one particular timestamp: the charcoal medium lends itself to the labour behind the sweet, sweet age of Industrialism — the birth of mass production, broadcasting, and rise of the nation state.

Park falls victim to the Era of Being Chronically Online, she’ll sometimes even lock her phone in a box for an entire day at the studio. It poses an interesting question for someone whose work is inspired by digital archives. Where is the sweet spot between “off-the-grid” and “information endowed” one needs to land on in the game of contemporary society Candy Land?

The women in Park’s work are fragmented, stunning and often cartoonised. Their exaggerated smiles are tried-and-true, always met by a voyeuristic gaze (IRL or via charcoal). While central to Park’s compositions, the damsel-esque figures often feel as though they’re meant to act as props. Visioned with a brilliant intersection between disembodiment and beauty, they remind me of something I once read in Sam Fox’s, The Mirror Makers: A History of American Advertising and Its Creators: “In order to sell something to someone, you must first distort their own reality.”

Park’s practice tributes the perfectly skewed image of femininity that’s been mass marketed and sold to women birthed by the national media ecosystem. Buy this now, look like her! Look like this! Look, look.

In the 19th century, folks found themselves enjoying the Golden Age of American Literature as a form of escapism. Today, we face a black mirror, reflecting our inverted faces and the vicious antics of the web. Park’s work isn’t pointing fingers. Instead, the larger-than-life typography against blurred, scattered and collaged imagery makes for the perfect duet to ode the anxieties around fast and easy media consumption.

In a way, Park’s oeuvre is archival — a visual recording of American culture and the way we’ve consumed it through ever-evolving sources. It’s a glamorous and cautionary tale of the media-dystopia we’ve wrapped in a big, shiny bow for generations to come. Nonetheless, her mastered craft and immaculate execution reveal triumphant. Park’s sleek renderings, clever language and remarkable grasp on materiality mirror the picture perfect, American made fantasy built by the proud minds behind the cameras that once inspired a much younger Miss Anna Park.

Written by Gwyneth Giller