Stephanie Wambugu speaks to Anna Thérèse Witenberg about her tense and erotic depiction of intimacy and envy in her latest composition Heat.

Anna Thérèse Witenberg is a dancer and choreographer living and working in New York City. After her sold out performance of Heat at the Brooklyn art space Pageant in September, she spoke to writer Stephanie Wambugu about her history with dance, her wide ranging literary influences, Italian horror, the Michael Mann movie which shares a name with her dance and the gift of working with friends. Heat is an original composition by Anna which features a trio of dancers negotiating intimacy and envy against an evocative and spectral score. On December 5-8, Anna will restage Heat at Kestrels, bringing the heartbreaking and ecstatic gestures that comprise Heat to a new venue and audience.

Anna, it was such a pleasure to see Heat at Pageant last month. Can you begin by discussing how you choreographed the actual movement in Heat? Is there an intuitive process you follow while choreographing? How much of this was allusive?

Heat started with an image that came to me of three women attempting to grind on each other in the club. Is it possible for three people to do a movement that is designed for two people? Rehearsals began with four months of the tedious development of this image. I am an anatomy fanatic and really interested in the bone structure of the pelvis. We started with the Pilates concept of a “pelvic clock”; rotating the pelvic bowl in a clockwise and counterclockwise direction to engage the deep abdominals. We would spend the four hour rehearsals practicing slow motion grinding while I would direct our pelvises, our bodies smashed right up against each other. “Hold four counts here, now Josie goes counterclockwise, now Rachel increases tempo”…etc all while feeling the heat of each other’s breath, our genitals on top of each other.

After months of laboring over a fraction-inch of rotation in the pelvis, I was itching to choreograph something large and explosive. So that’s when I developed Rachel and my duet, which is an homage to our personal dance history:Lucinda Childs, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Pina Bausch. This duet is really about our dance training, about the aspiration innate to training in classical forms, about the competition/partnership that is the fellow dance partner.

Next came Rachel’s solo, which was about fulfilling a childhood fantasy: Fame, Fosse, Cabaret, Jlo, all of that was in there. It’s a totally sincere, and un-sarcastic expression of virtuosity and sensuality. Following that I made Josie’s solo. The choreography is very emotive: small minced steps on relevé, rotating from the ribs with one hand on her chest and the other dragging behind her with a clenched fist. I started by working with the internal landscape of her body: I asked her to imagine that she was towing something behind herself, a harrowing feeling. Josie used to say she is “dragging her entrails” onto the stage.

I worked on the next part of her solo very closely with Jack, the composer. Each movement aligns carefully with the phrasing of the music. To prepare for this method of choreographing, I spent a week learning the musical/choreographic intricacies of Bejart’s Bolero, performed by Jorge Donn, a legendary Argentine ballet dancer. I was fascinated by Jorge Donn’s particular interpretation of the solo, the way his hips sort of wrap around a note of music, rather than land in the center of it. I wanted Josie to have that same quality—circling a precise musical note and personal feeling with hesitation, fear.

Can you say a bit more about the sincerity and earnestness of the dance and how that came up against moments of humor and levity? There was a moment when the audience laughed and I thought it was such a striking contrast to the rest of the dance which was quite emotionally intense. A friend who attended Heat on the same night that I did told me she was moved to tears, I imagine she wasn’t alone.

The dance is about love. The love of dancing, the heartbreak of being a dancer in New York without any real prospects except for the intimacy it gives you with your friends. And yet what an honor it is to live this life. It is profoundly meaningful to me that the work moved people to tears, but it would be OK if it didn’t, also. All I wanted to do was express what was deep in my soul – this agitation, this yearning, searching. And Rachel, Josie, and Jack are the God-sent stewards of this truth. They made my dream come true- making a dance like this was all I’ve ever wanted in my life.

There’s a connection made between your dance and the Michael Mann film Heat (1995) in the text for the show, but I’m curious about other texts, films, or dances you hoped to evoke in your performance?

I had never seen the movie Heat until a few weeks before the premiere. I was using a song from the soundtrack to make Rachel’s solo (the only piece of music in the entire show that wasn’t composed by Jack). I decided to call it Heat after the dance was already finished because of the song and the internal fire produced by the dance itself. My friend Mara Mckevitt, who wrote the press release text, equated the two as having a structural similarity. I like the comparison, because the movie Heat is about a standoff between two people, whereas the dance Heat is about three people trying to access the centerpoint of intimacy, and about asking yourself where you fall in the eyes of the other.

The most substantial literary influence of this dance is the 1934 play “The Children’s Hour” by Lillian Harman, which is about two headmistresses of an all girl’s school being accused of having a sexual relationship by a vengeful pupil that was expelled. She claims to have seen them kissing between the keyhole of a door. This image, of two women embracing, seen by a little girl through the sliver of a keyhole, really stayed with me. The play unfolds as a triangle between a pubescent girl and two adult women. I wasn’t interested in the sexual aspect so much as the energetic fragmentation–women becoming intimate emotionally, pulling apart, being watched by a young girl who desireness closeness, wanting to enter the center, wanting to be seen, etc.

Another major influence is Fleur Jaeggy’s Sweet Days of Discipline which is about a friendship between two young girls in boarding school and how their enmeshment shifts between fascination and repulsion. I have experienced this a lot in my friendships, the closeness between girlfriends, an intimacy that could be considered by the outside world/viewer as erotic, but for me is too simple of a classification. These friendships move you so deeply that you feel like you are inside each other, one in the same. One day fusing, the other day splitting apart. Jaeggy’s writing is stark, blunt, tender, even violent at times. Her style of writing and punctuation helped me to form a directorial syntax.

Both of these stories take place at a boarding school; confined, claustrophobic enclosures. Heat takes place in the dance studio, another kind of hotbed for anxiety. Lorenzo Bueno, the set designer, did an excellent job of transforming Pageant into memories of the dance studios I grew up in and videos I’ve watched of ballet studios in Soviet Russia.

Part of what felt so tense and erotic in this dance was the tension between the different dyads that emerge at different moments between you, Josie and Rachel. Can you talk about why you selected the dancers that you did and what the pair, as a form, means to you?

It happened organically. Rachel and Josie were both interested in working with me and I find them both so totally mesmerizing. All three of us share the feeling that dancing is a sacred act, to be guarded at all costs. And we could all laugh together! I felt from the first day of rehearsal I knew I had made the right choice because we could just have fun and could tease each other. That silliness is all over the world of the piece.

Ann Carson, describing an excerpt from Saphho’s Fragment 31, describes the erotic triangle as the point at which “the three components of desire all become visible at once in a sort of electrification”. I constructed the dance to be mostly duets, with one dancer always watching- shut out, yearning to be on the inside. The dancer’s desires are constantly being shaped by lack, such as when Rachel leaves me to dance with Josie and I am left wondering what she has that I don’t. This is also what it means to be a dancer for me, to always feel insufficient.

I didn’t realize this until the dance premiered, but Heat is actually about the jealousy and idolatry that happens amongst dancers in the studio. We became very very close friends over the year of making this piece. We were constantly gushing over one another, encouraging one another, admiring each other and yet quietly comparing ourselves to each other in these small but insidious ways.

Can you say more about the interplay between friendship, jealousy, eroticism in the dance? Do these themes have any relationship to your experience as a dancer?

Being a dancer is competitive, there’s no way around it. Dance class is structured so that you do the exercise, then you scurry to the back of the room and watch the other group of dancers do the exercise. For me it’s impossible not to compare myself to the best dancer in the class, the one I’ve always wanted to be. It’s an achy feeling I’ve felt my entire life, watching another dancer and every part of you just wanting that. To feel what she feels while she dances. I have decent technique but it’s nowhere near Rachel’s. So for me, the opening duet is about striving, wanting to match or meld with her beauty. It’s aspirational.

So I am starting to realize that Heat is really about the deep love and envy I have for the dancers I spend my life with in the studio. The obsession that always mixes with jealousy; a competition turned sensual and fluid. Studying each other’s bodies closely; memorizing each groove of her foot, knowing exactly how she will strike her jump, how she will prep her turn, watching her for hours on end; staring, touching, feeling. Wishing to be her; wanting to be better than her. The deep intimacy that is knowing your dance partners rhythms, instincts, smells.

I know that Jack Whitescarver, who composed the score, is also a close friend of yours. How did you go about working on the music together and what, if anything, served as inspiration for the score?

Jack is brilliant and has a distinct and singular approach to making art. He has an encyclopedic knowledge of film, visual, art and music, and my sense is that when he sits down to compose music, all of human history flows through him. I can feel it in his body when he plays music.

We wanted the music to have the feel of giallo films, an Italian genre of horror films whose soundtracks are characterized by synthy, pathos driven melodies. We dove into hundreds of references to make the score: a medieval mystic and composer Hildegard Von Bingen, a self proclaimed Satanic vocalist from the 80s called Diamanda Galas, Phillip Glass and the whole minimalist tradition, a few chords from the Ganja & Hess soundtrack. Sometimes I would just hear a horn on the street, record it and send it to Jack, saying something like “I like the pitch, can we add this to Josie’s entrance?” I would go over to his apartment and we would mess around with instruments, throwing books around the apartment, recording the sound of me walking in heels. We were thinking a lot about medieval chord structures, leaving the audience with something that would resonate in their bodies as ancient, primordial, calling from a distant past.

My favorite piece of music he wrote is the ballad he sings at the very end. The lyrics are: “He is a guide he calls her with a handshake//Three are the gifts that will shine brightly before the dawn// And there is the place where his sister is, she will shine.//

This song lifts us to higher places, beyond our pain. His voice is so beautiful. It has always sounded to me like a howling, heartbroken werewolf.

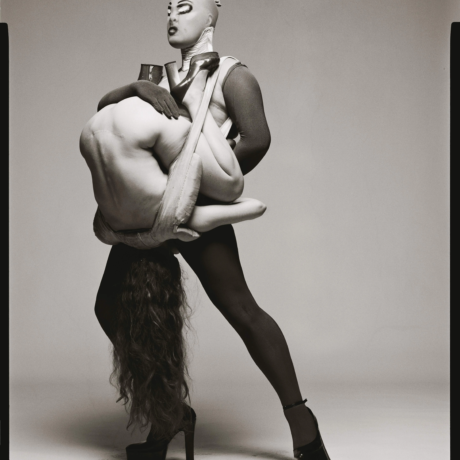

We spoke about the styling in the show and how the stylist Dylan Keoni selected pieces designed by figures from the Antwerp Six. We talked briefly about fashion as a kind of shared idiom, and I wonder if you could say more about this and what it meant to wear clothes made by Ann Demeulemeester or Dries Van Noten, as opposed to the kinds of costumes dancers typically wear? (Apart from the fact that it was all very chic and glamorous!)

From the beginning I knew I wanted the dancers to wear the Antwerp Six, who were a group of designers making clothes in the early 1980s in Belgium. These are a group of designers who really fit the tone of the world I was creating: austere, feminine, sensual. I just didn’t know how to get those clothes without spending a fortune. I ended up meeting Dylan in a park one afternoon with some other friends. I learned she is a very devoted archivist, researcher, model, and stylist who has dedicated a lot of her life to carefully studying and collecting Ann Demuemeester. She came to rehearsal and was excited at the idea of styling us in her personal collection. It is so magical to wear these clothes, crafted with meticulous detail. In this dance, every part of our bodies is so carefully considered that we needed to wear garments that were made with the same degree of precision and styled with the same degree of attention. The clothes carry a history; Dylan’s obsession, her idolatry of Ann. It aligned perfectly with our world, her compulsion and infatuation towards another woman. Looking glamorous is not superficial- it is essential for this work. This dance asks you to lean in and look closer; asks you to observe the seams, edges, embroidery.

You talk about wanting to leave viewers with the sense of something ancient, whether that be through the use of medieval chord structures or by evoking old, timeless themes (jealousy, desire). Many of your answers betray an affinity or deep engagement with the literature, music and film from the past. Even a contemporary writer like Fleur Jaeggy feels out of step with contemporary culture and writes in a way that evokes bygone ways of living. In light of this, how do you feel your dance engages with contemporary life? What do you hope to go on to make in the future?

Dancing and making dances is a way of being present for myself and my friends. It’s a way of slowing down time and asking myself “what really matters?” All I can hope for is the ability to cultivate the financial means to make another dance with other people, that alone is a massive privilege that I am hoping can happen again, next time more comfortably. I want to work more deeply, and better resourced: increased wages for the collaborators, sprung floored dance studios so we get less injured. I would also love to be able to pay for my dancer’s physical therapy.

It has always been a dream to work on a classical Opera, to choreograph the dance libretto. I have also always dreamed of choreographing a runway show. In both cases, the idea of working with really stunning garments, creating a conversation between body and clothing is very exciting to me. How can I infuse a deep sense of feeling and narrative into a garment, animate it. My friend Daphne really taught me about the narrative that is innate to a garment, how it describes time and inflects meaning. This is a realm I want to go deeper into.

Heat features dancers Josie Bettman and Rachel Gill, with original musical score by Jack Whitescarver. Set and lighting design by Lorenzo Bueno and styling by Dylan Keoni. The version at Kestrels will include lighting by Cameron Barnett.

Words by Stephanie Wambugu