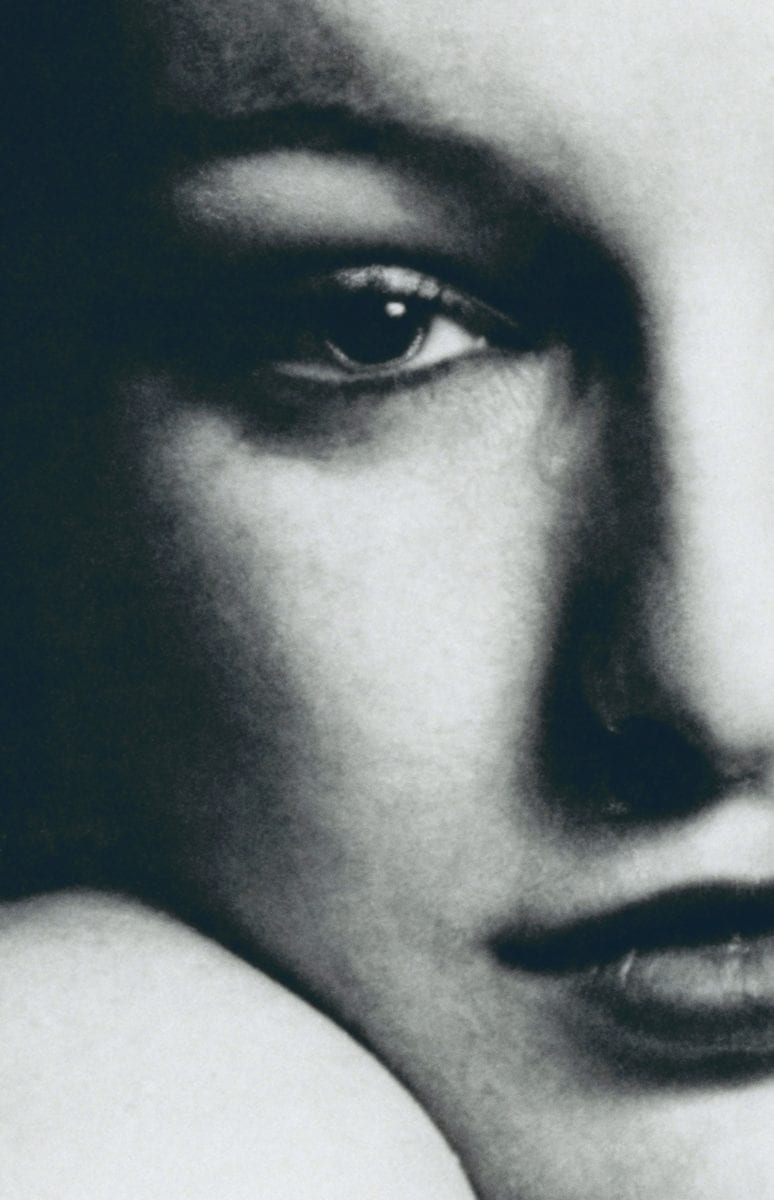

At first, the mesmerizing face of Marilyn Monroe on copies of Norman Mailer’s biography of the star captivate because of her dreamy look. But American artist Anne Collier’s clinical photographic rendering of the books—shot against a neutral backdrop in even lighting—reveal far more than Monroe’s surface expression; on closer inspection the tatty edges of the books become tantalizingly apparent, hinting at the past lives of these tomes. Presented in this meticulous way the books are like specimens that might be of interest to a forensic scientist or to an archaeologist. Collier invites us to study the differences between items that on the surface look to be the same, but are in fact anything but; the pass of time has made each unique.

Indeed it has been said that Collier, who studied at CalArts and UCLA in Los Angeles, has a forensic interest in the objects she photographs, and her artworks have been described as photographic excavations. It makes sense, then, to discover that the artist has a longstanding interest in objects that bear signs of their previous lives, objects that show they have been “used and abandoned” by their previous owners.

“The message was clear: that professional photography was something men did”

“I have a large collection of other people’s family photographs that show women with cameras, and women in the act of taking photographs,” says Collier, who lives and works in New York. “I’m interested in how these ostensibly private images have entered the public domain. This threshold—between the private and the public realm—has been disrupted by different forms of social media, but my interests remain rooted in physical manifestations of photographic imagery, and the visceral relationships that we develop with such artefacts.”

- Left: After You Get What You Want (Recto), 2017. Right: Album (The Amazing), 2015

Collier’s interest in “objects that act as vehicles for photographic imagery” has led the artist to collect everything from album sleeves and posters to photography magazines and postcards. Collier recounts how in the early 2000s she trawled bookshops, record stores, thrift shops and flea markets in the Bay Area where she was living (“the best store was in San Francisco—The Magazine, on Larkin Street—an amazing source for vintage photography magazines, which I still visit whenever I go to the Bay Area”), and in the years since she has amassed a collection of photographic objects that include those depicting women, often in sexualized or objectified ways.

At the heart of Collier’s practice is an exploration of photography’s gendered nature for example, how deeply ingrained sexism plays out in photography magazines from past decades, but moreover, how this is evident in the culture of photography as a whole. “I started collecting professional photographic magazines and journals, mostly from the 1970s and 1980s, where women were typically relegated to the status of ‘props’—posing with cameras and camera equipment, or acting out as if they were taking photographs,” says Collier.

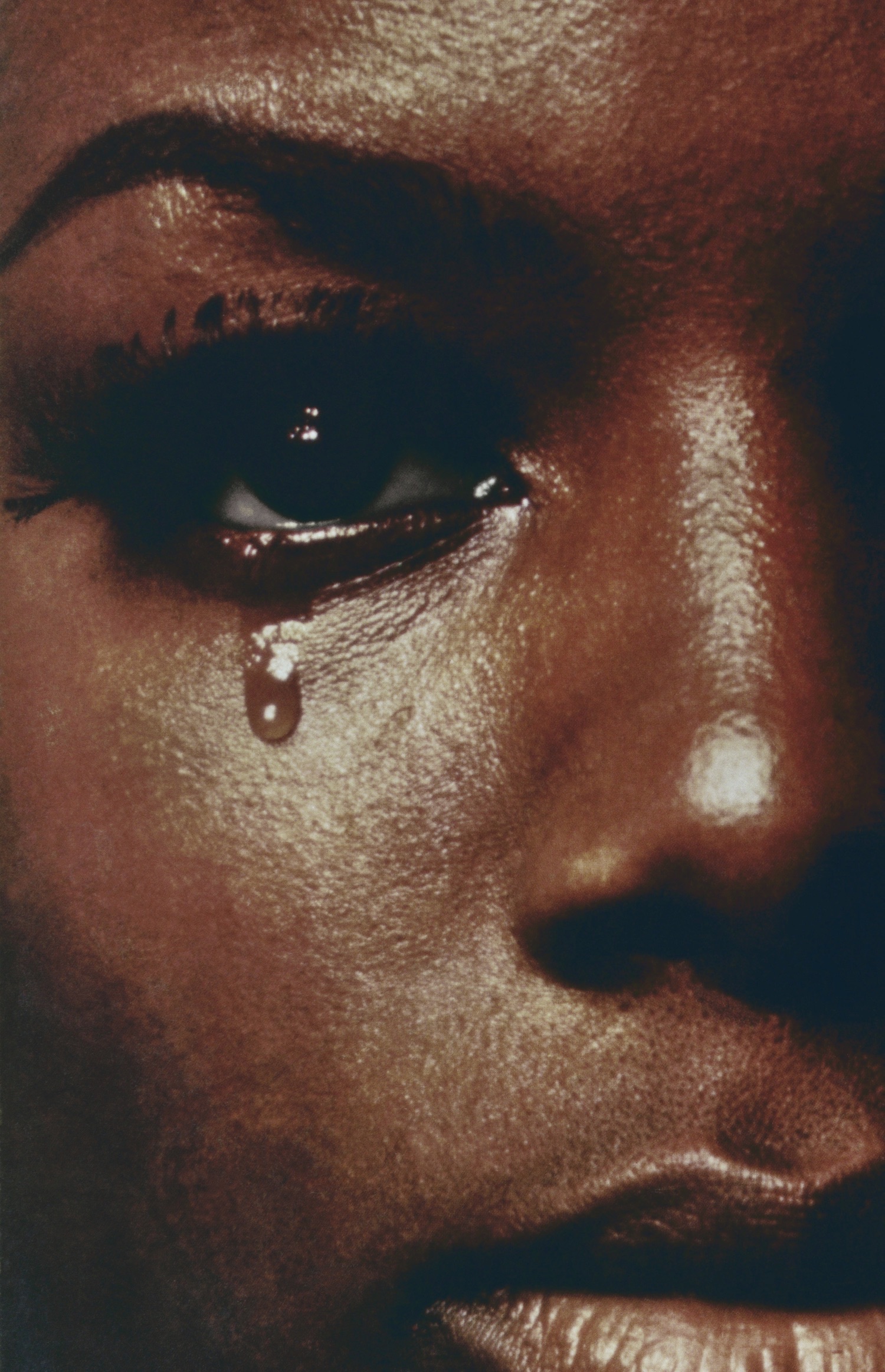

“The message was clear: that professional photography was something men did. I also started to collect records that featured different forms of visual clichés on their covers—for example: sunsets, people smoking, women crying, images of eyes, and so on—as well as paraphernalia relating to the self-help and ‘pop-psychology’ industries. All of these materials eventually found a place within my practice.”

Exactly how these photographic objects and the images contained within them have been incorporated into Collier’s work is ranging, multifaceted and complex. She has made photographs of self-help cassette tapes in Introduction, Fear, Anger, Despair, Guilt, Hope, Joy, Love/Conclusion, photographed in what would become her characteristic “deadpan” way. And her Woman with a Camera work explores the objectification of women in photography by isolating and recording photographically the objects (for example, magazine spreads) that objectify the women depicted, including images of actresses posing with cameras.

More recently, Collier produced a series of artworks that show close-ups of images of women crying, which she sourced from album covers between the late 1960s and early 1980s. In these cropped and enlarged image fragments, Collier invites us to ponder the staged, manufactured emotion on display—emotion that is hollow and fake, yet in Collier’s work becomes strangely affecting.

Born in 1970, Collier has said that she has been and remains influenced by artists of the so-called Pictures Generation—including Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince and Louise Lawler who in the 1970s into the 1980s responded critically to the media landscape of the time—although she doesn’t strictly think of her work in terms of appropriation.

“I’m interested in how these objects/images circulated, how they were experienced and consumed,” Collier comments with regard to her work overall. “The legacy of appropriation is clearly a reference, but I’ve always associated appropriation with a questioning of, or even a challenge to the notion of ‘authorship’. So even though I often take photographs of existing artefacts such as records, books, magazines, film stills, posters and so on that feature or incorporate imagery created by others, I think it remains clear that I am not claiming authorship of either these artefacts or images.”

What she is after is an aesthetic clarity, Collier has said, and her interest in drawing inspiration from the techniques and even cliches of commercial photography is clearly discernible. She remains interested in “the seductive aspect of images and image-making” and how this plays out through images created “in the service of marketing or advertising—for example how images were used in relationship to popular music and fashion”. By re-presenting or reframing the images in the ways she does, Collier distances them from their original intention or purpose, but in doing so “open[s] up the potential for new readings or other narratives”.

Integral to her work is the process with which she photographs her chosen objects. Using a large-format camera in a studio Collier photographs against a plain background, giving the artworks a degree of uniformity even though each is undoubtedly individual. It is a process that doesn’t allow much room to improvise. “The studio plays an important role in my images as a ‘stage’ where the objects I document are arranged or choreographed,” Collier explains. “In that respect my work is technically still-life photography in that I’m trying to create an essentially objective image, albeit of artefacts or objects that often have complex psychological or subjective histories. This tension or even discrepancy between what is depicted in my work and the manner of its depiction is central to my approach.”

- Left: Woman Crying #1, 2016. Right: Woman Crying #3, 2016

Her work has been said to have an autobiographical dimension, and critics have commented on the coolness of her shooting style and how despite this apparent detachment there is paradoxically a discernible sense of Collier the person and artist. Explicitly placing herself in her work proved problematic early on, she says, so Collier changed tack, moving away from making overtly autobiographical work and instead embracing a more nuanced approach.

“This oblique approach to self-portraiture remains something I’m interested in negotiating in my work”

“My earlier work—when I was at college—often took the form of self-portraiture, where I literally appeared within the image,” she says. “Over time, my presence in these images became more marginal and incidental to a point where it was often hard to actually register my presence in the image. I’ve described aspects of my subsequent work as a form of ‘deflected self-portraiture’ where I was trying to find objects or artefacts that could somehow operate as ‘surrogates’ for aspects of my own identity, my personality, and so on, hence my interest in, say, the products of the self-help and ‘pop-psychology’ industries, or images featuring women posing with cameras. This oblique approach to self-portraiture remains something I’m interested in negotiating in my work.

“My hope is that the things I incorporate resonate on both a personal, autobiographical level as well as on a more general, and perhaps even universal level… I’m often drawn to imagery that I would describe broadly as ‘biographical’, i.e. images that pertain to my childhood and adolescence in the late 1970s and 1980s that as I suggested might function as ‘stand-ins’ for aspects of my own life or identity. I don’t necessarily think about these interests as being nostalgic per se, but perhaps more related to an interest in melancholia.”

Anne Collier is showing at Sprengel Museum, Hannover until 6 Jan 2019

This feature originally appeared in issue 33

BUY ISSUE 33