Paz Errázuriz Evelyn, La Palmera, Santiago From the series La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple), 1983 © Paz Errázuriz / Courtesy of the artist

Evelyn wears sangria-red lipstick, rosé blusher and a cobalt-blue slip with a matching fabric collar. Her silver, feather-shaped earrings glint as she peers back at the viewer from beneath a dense canopy of eyeshadow and bushy hair. In the dim light, she cuts a striking figure against the mustard wallpaper behind her. This 1983 photograph by Paz Errázuriz forms part of a series called Adam’s Apple, starring male cross-dressing prostitutes who lived in Chile in the 1980s. Evelyn was one of them.

Under General Pinochet’s military dictatorship, these prostitutes lived in fear of being rounded up and subjected to beatings by the police. Errázuriz’s project of documenting their lives has come to represent an act of political dissent that has seen her commonly dubbed “the woman who defied Pinochet”. Now, it is also part of a monumental new London exhibition celebrating photographs of outsiders like Evelyn: Another Kind of Life.

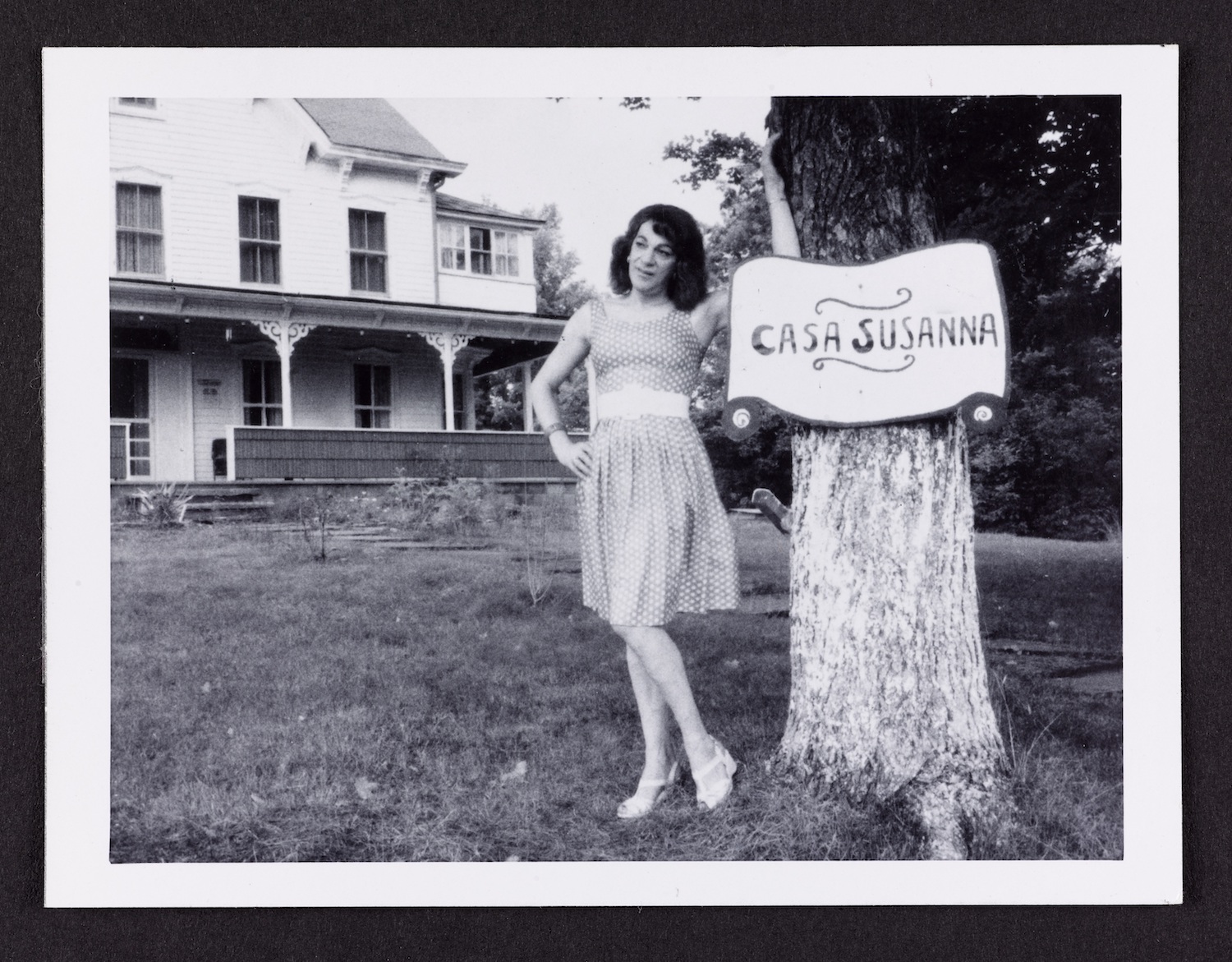

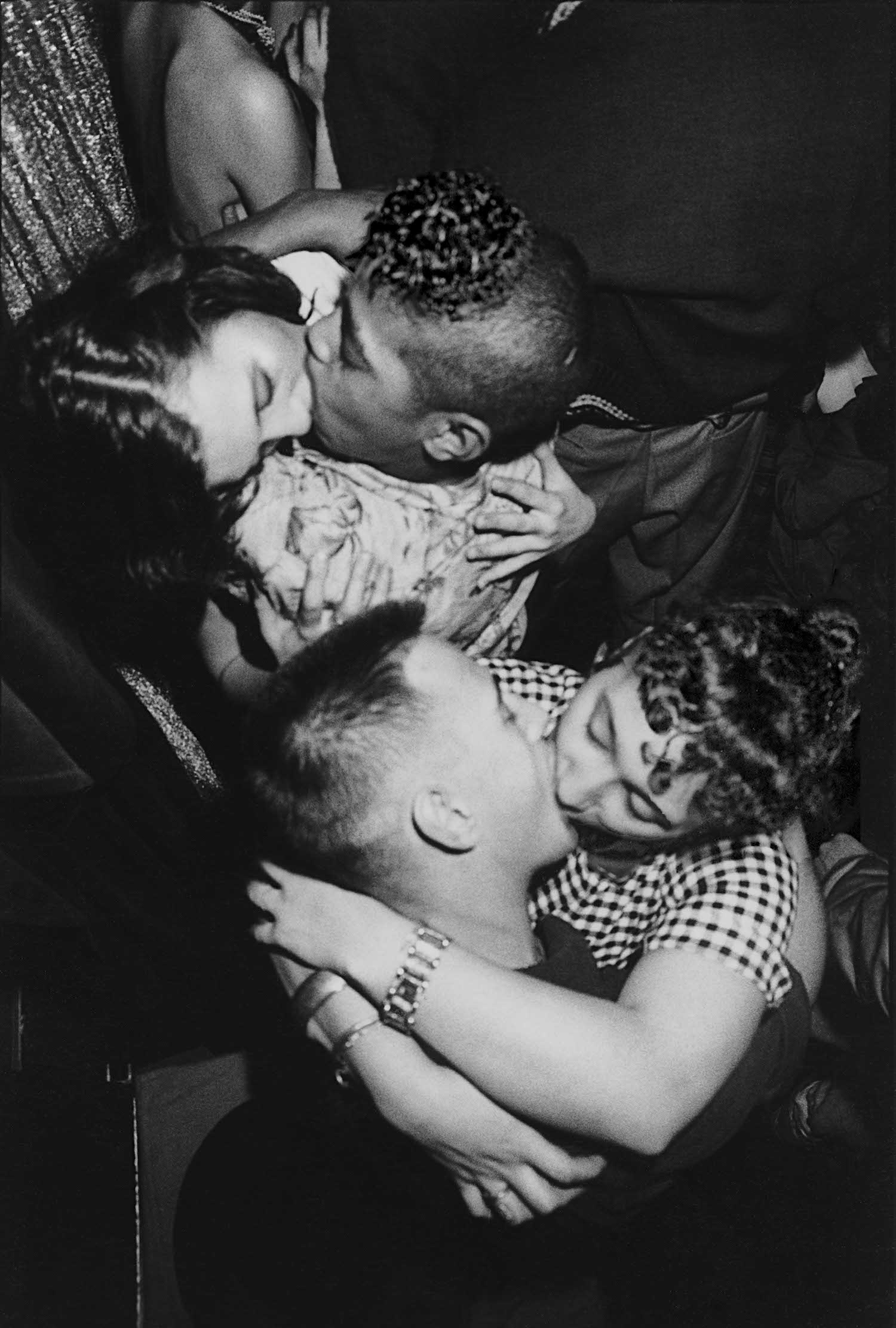

The show brings together more than three hundred images from twenty photographers who captured the lives of people on the fringes of society. Each photographer’s room constitutes a mini exhibition in its own right, ranging from a series of 1950s images of a private retreat for transvestites in New York, to Pieter Hugo’s mid-2000s work documenting a remote Nigerian community which lives with the country’s much reviled hyenas. Errázuriz’s room, made up entirely of the Adam’s Apple series, fills part of the considerable space between.

It was the fact that her subjects were shunned from mainstream society that made them fascinating, according to Errázuriz. The series began less as a two-fingers to the dictatorship, she says as we examine the mostly monochrome series, and more as simple human-interest. “This work is like studying identity for me. I’d never seen anything about prostitution in my country with what was happening, so I had to capture it myself,” she explains.

But over the five years spent photographing them she grew close to the sex workers, especially Evelyn and her brother, Pilar. “Evelyn was very neurotic and self-conscious, but Pilar was terribly sympathetic and helpful, and helped their mother a lot.” Errázuriz ceased to feel like an outsider looking in and became “part of the family”. This eventually led to grief, however, as they both died of AIDS a few years later. “I got to know them so well,” she says. “I followed Evelyn for many years and had a good friendship with her. It was very tragic in the end.”

The notion of the photographer as an outsider is shared by the work of Japanese photographer Seiji Kurata, whose 1970s shots of Tokyo’s seedy underbelly are laced with drama. Among them are members of the notorious Yakuza gang: one man stands on a rooftop in his underpants, floral tattoos covering his body in place of clothes. Photographed in 1975, he stares down his nose into the camera, and in his right hand holds a gleaming samurai sword as long as his leg.

Similarly confrontational are the subjects of a handful of photos taken in the mid 2000s by South African-born Pieter Hugo. After hearing about a nomadic group of Nigerian entertainers whose party included four monkeys, three hyenas and a python, he went to live with them intermittently for two years. Many in Nigeria, says the artist, think hyenas are witches, or humans “reincarnated as wild beasts to cause mischief and havoc in the night.”

“The common thread here is that the photographer ceases to become an outsider looking in, but almost a member of the communities pictured.”

The subsequent response to the group, called Gadawan Kura (hyena handlers), is one of suspicion and curiosity. This is perhaps the reason for Abdullah Mohammad’s defiant glare into the lense as he holds his hyena, Mainasara, on a leash. In one image Mainasara stands on hind legs, hugging Abdullah Mohammad around his waist, incongruous white oil tankers parked behind them. The hyena’s muzzle makes the viewer wonder just how tame it actually is, but the rare intimacy between the man and his unconventional familiar is fascinating.

Be it Chile, Japan or Nigeria, each room of the exhibition is firmly rooted in one location. The show’s curator, Alona Pardo, explains that this is to illustrate the narrative qualities of each artist. “They’re telling stories not through a singular image but through a body of work,” she says. “We wanted to root it in those particular experiences that the artists had with those communities that they were photographing.”

And what about the sheer historical and global breadth of the exhibition? “What’s fascinating is that artists connect because these communities are dealing with the same discriminations no matter where they are in the world,” she explains. “Perhaps in more liberal, metropolitan areas change has happened quicker,” she says, “but whether its Mexico in 2016 or America in the 1960s they were facing the same levels of adversity.”

Of course, the show doesn’t shy away from these liberal, metropolitan areas either, and a key component of this is the room devoted to Larry Clark, director of the seminal 1995 coming-of-age film, Kids. His work on display here, however, dates from the 1960s and early 70s. Shot in his home town of Tulsa, Oklahoma, between stints as an art student in New York and a soldier in Vietnam, Clark paints a stark portrait of his contemporaries. The images revolve around heroin use and misspent youth, and a short video shows a young man in a white t-shirt with a thick mop of hair shooting up with the help of his friend. His expression of bewilderment and unstable attempts to stand up betray the sudden rush he feels.

American photographers Mary Ellen Mark and Jim Goldberg feature prominently too. The former’s 1983 project, Streetwise, follows a girl named ‘Tiny’, who lives on the streets of Seattle, along with others in her position. Meanwhile, Goldberg’s close relationship with the homeless people he photographed shines through in his work shot in Los Angeles and San Francisco during the 90s. Similar to Errázuriz, the common thread here is that the photographer ceases to become an outsider looking in, but almost a member of the communities pictured. In such a huge exhibition, the subsequent level of intimacy between viewer and subject is often totally disarming. It is no mean feat.

Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins

28 February until 27 May 2018 at The Barbican Centre, London.

VISIT WEBSITE