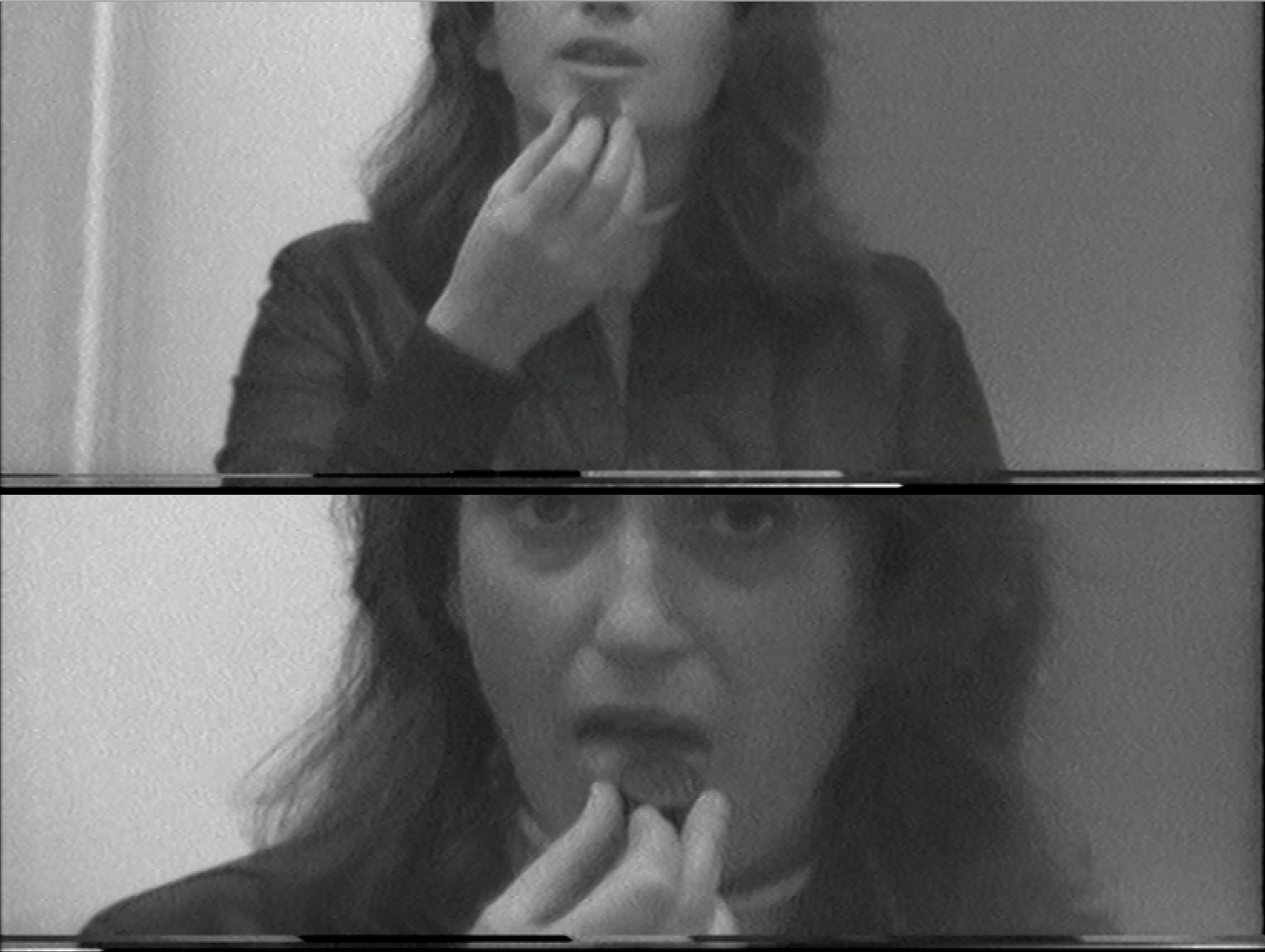

VALIE EXPORT, The Sweet Number: An Experience of Consumption, 1968 (film still). Courtesy Another Gaze

A woman balances a plate on her head while slowly and deliberately spooning melon from her bra; rats nibble at a pair of dangling cherries; a box of chocolates is cynically compared to a Van Gogh painting. This is Eating / The Other, an eclectic programme of six short experimental films, loosely linked by their focus on food, selected by the non-for-profit feminist film journal Another Gaze. These shorts are showing for free as part of the magazine’s newly-launched streaming platform Another Screen, a riposte to the vast selection of content to be found on platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and even the more curated pages of Mubi. In an age of infinite choice, how can an audience be expected to find their way?

Founded in 2016 by Daniella Shreir and co-edited with Missouri Williams, Another Gaze

cuts through the noise. The pair position themselves “as a feminist voice, one that is not purely celebratory but justly cynical and critical,” Shreir tells me over the phone. In the magazine you are as likely to find a stinging criticism of the so-called ‘millennial woman’ as you are a takedown of film rankings titled simply ‘Against Lists’. Their focus is on overlooked women filmmakers, “whose names often can’t be found beyond the pages of academic journals”, with the aim of introducing them to a wider audience.

- Patty Chang, Melons, 1998 (film still). Courtesy Another Gaze

“I believe that everyone can find an entry point into experimental cinema. I am cynical of what we’re spoon-fed in UK film culture”

This renewed accessibility includes moving beyond the anglocentric focus that often dominates film circles. After realising that many of their readers around the world were using Google Translate to read the English-language texts published on their website, Shreir (who also works as a professional translator) set about expanding their points of entry. Another Screen offers subtitles to its film programmes in a growing number of languages, which currently includes French, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, Japanese, Korean and Indonesian, as well as English, and are often able to negotiate fees for screening rights in exchange for subtitles. “It became a way to include voices from a more global film community.”

Born and raised in London, Shreir expresses disappointment at the city’s film culture: “Distributors and cinemas really don’t trust the audience; they assume that with subtitled films, people won’t go to see them. Even at the British Film Institute, who should be at the forefront, there is so little shown that is actually interesting or non-didactic, or which requires the audience to do some work.” Another Screen sets out to provide a new way of showing and watching experimental films anywhere in the world, moving beyond the typical format of the museum where shorts are often screened on a loop. “I believe that everyone can find an entry point into experimental cinema,” says Shreir. “It brings me back to my cynicism of what we’re spoon-fed in UK film culture.”

Another Screen kicked off in March of this year with a “One-Woman Confessional” of eight short films by Cecilia Mangini, the censored Italian documentary filmmaker who died of Covid-19 at the age of 93 in January. Mangini’s death sparked renewed global interest in her work (“I’ve talked to older filmmakers who say the best move you can make as a woman filmmaker is to die,” Shreir groans), bringing her multi-layered explorations of social inequality, ritual and youth to new audiences. The Another Screen website is designed to offer a contextual base with which to navigate the programme, featuring long-form text and imagery alongside the films themselves. “Various foundations and museums have shown films online during the pandemic but it’s always just a white screen with a black rectangle,” Shreir says.

Mangini was followed by two thematic programmes, the first related to hands and the second to food. “I was wary of the limits of a thematic structure, an imposed framing, but it’s about trusting your audience and realising there are unlimited interpretations.” The Hands Tied programme brought together two films, Palmistry (1973) by Austrian artist Maria Lassnig and Ayesha Hameed’s 2016 A Rough History (of the Destruction of Fingerprints), accompanied by a roundtable discussion on fate, work, pleasure, touch and surveillance.

“The internet isn’t necessarily a utopian space but it can be used to create a forum for these different voices and communities”

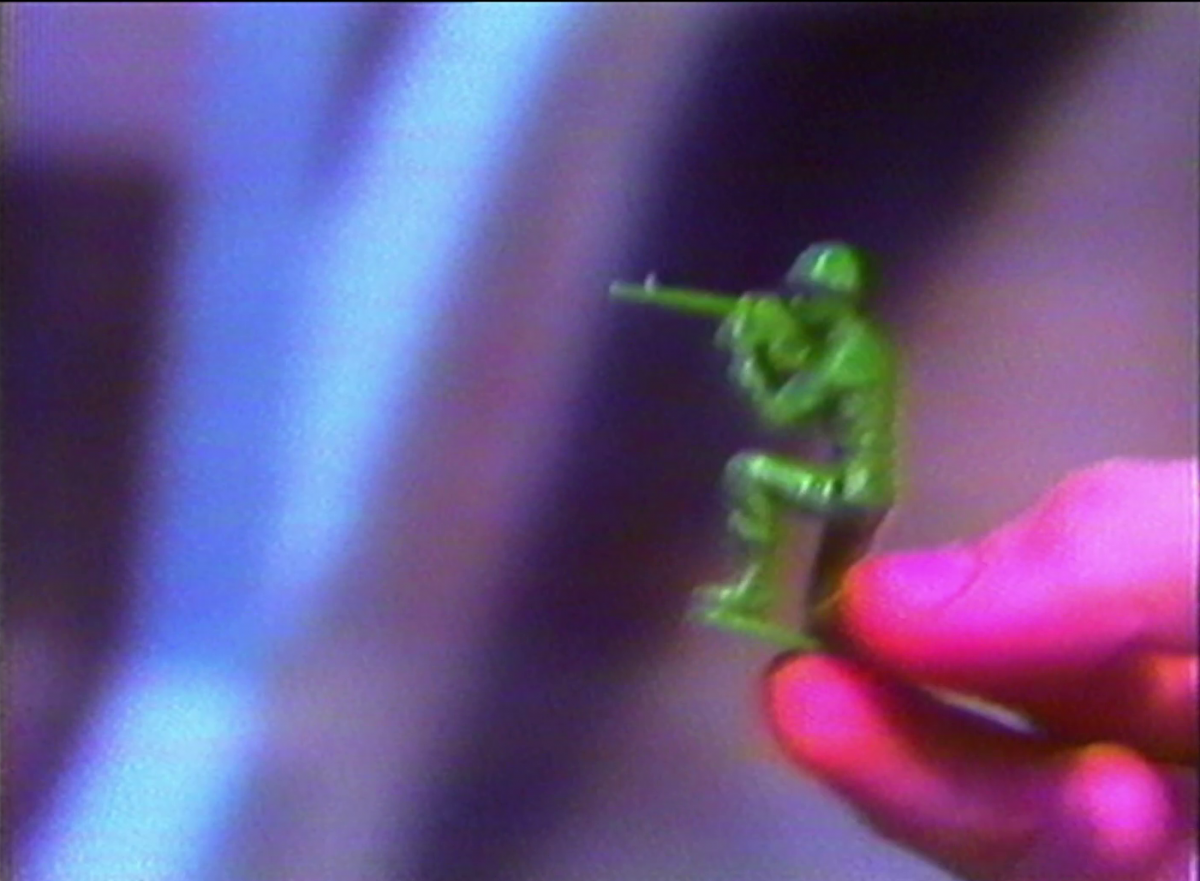

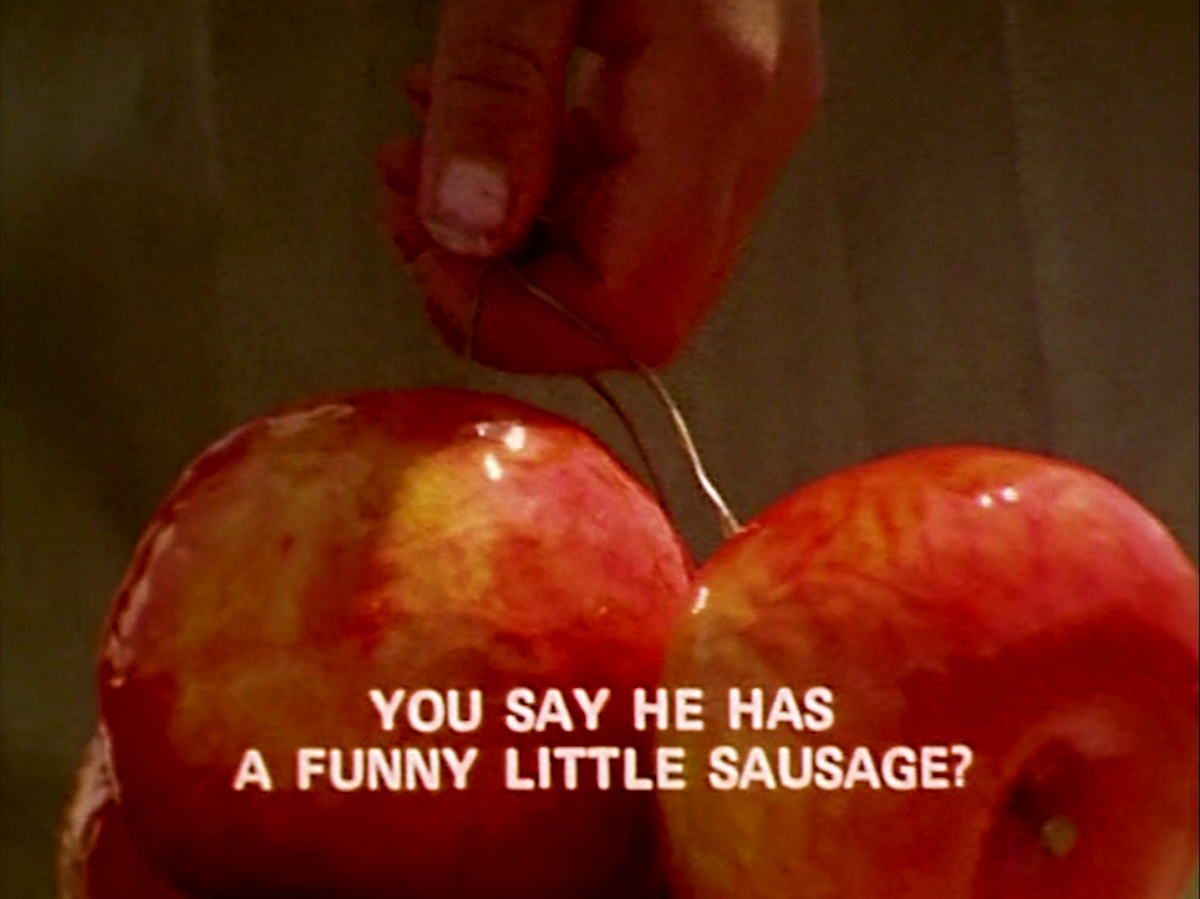

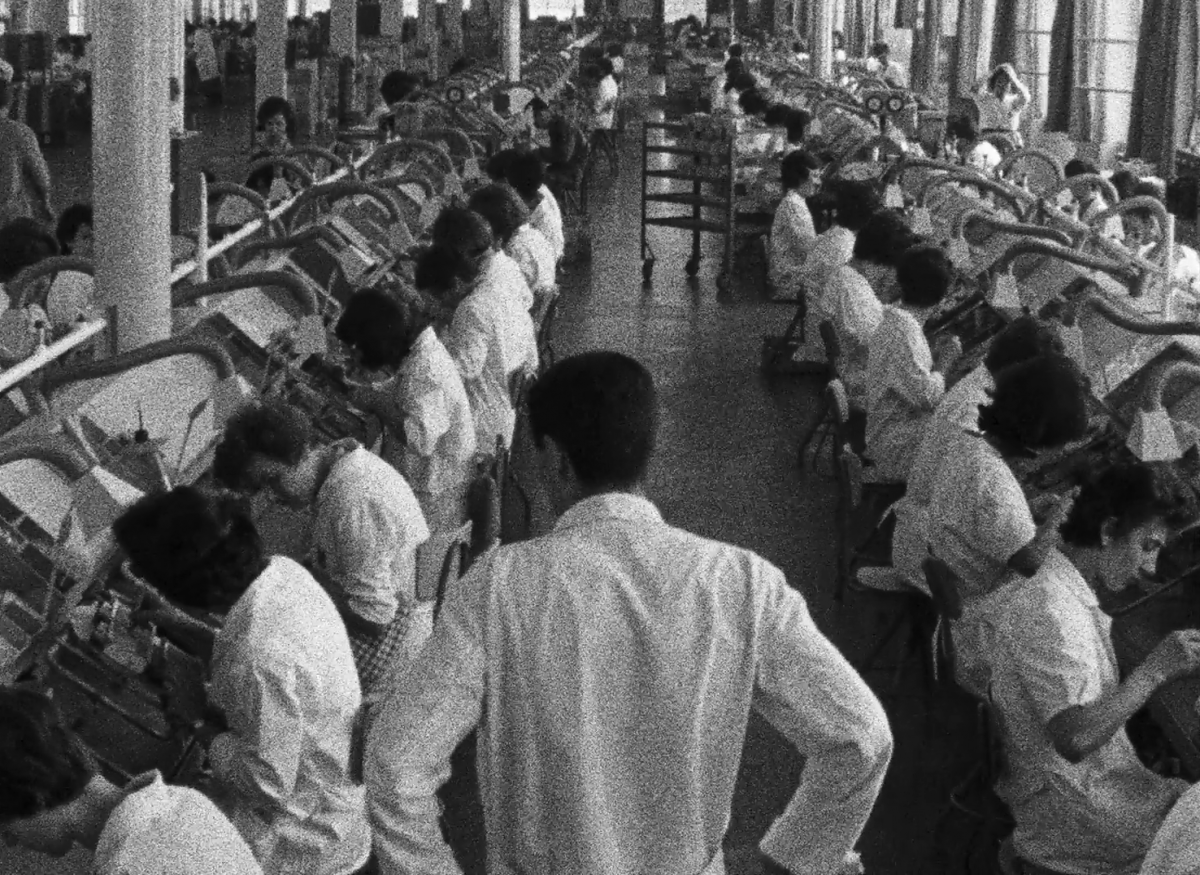

Eating / The Other uses food to address everything from grief to migration, political dictatorships to childhood and play. Shreir points to food as a major discussion point in relation to gender in recent years, from the resurgence in popularity of Věra Chytilová’s 1966 Daisies to the discussions of a more hyperbolic female appetite portrayed in Blue Is the Warmest Colour, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2013. In Another Screen’s programme, Melons (1998) by performance and video artist Patty Chang sees her ritualistically sever a single fruit-filled artificial breast, while pioneering avant-garde Austrian artist VALIE EXPORT represses a laugh as she feasts on chocolates in The Sweet Number: An Experience of Consumption (1968). The programme is at turns lyrical, biting, and highly digestible.

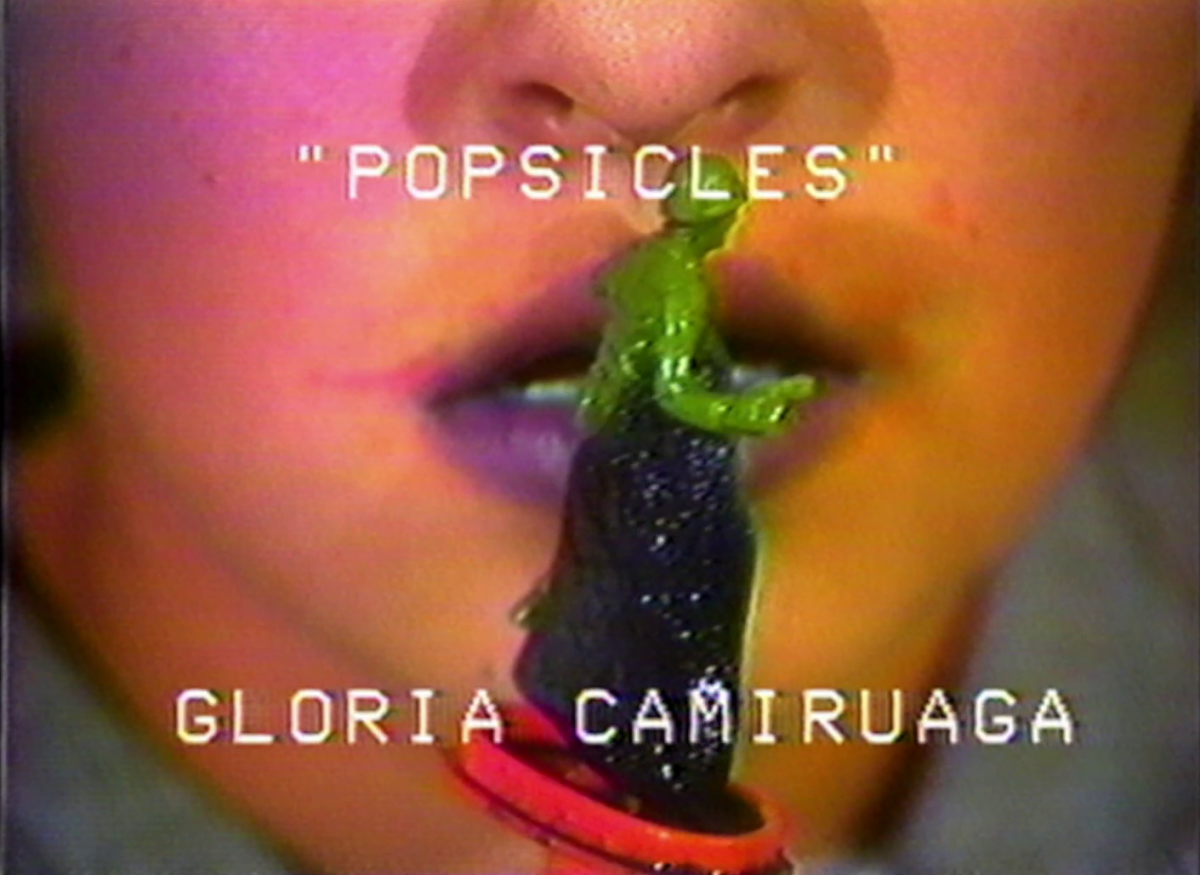

- Gloria Camiruaga, Popsicles, 1986 (film still). Courtesy Another Gaze

Following a year of various lockdown restrictions, Another Screen is arguably a product of the pandemic. “Covid has made us realise that, even though we thought we were reliant on technology before, we weren’t even using it to its full potential,” Shreir says. “The internet isn’t necessarily a utopian space but it can be used to create a forum for these different voices and communities.” She argues that it has been smaller outlets that have been the most prolific under these restricted conditions. “The more marginalised art places have been doing the best things, while the more established ones have been on furlough. There hasn’t been nearly as much innovation from the bigger art spaces.”

Another Screen is not resting easy. Next up is Silence / Laughter, another thematic programme that this time explores repression, hysteria and the psychiatrisation of female killers. Even as museums and cinemas around the world gradually reopen, the popularity of streaming platforms is here to stay. It represents a shift of power from the global epicentres of cities such as London and New York, whereby people from all over the world can access film programmes typically reserved for festival and exhibition screenings. Covid has made it clearer than ever just how important culture is for our existence, offering solace and community when we need it most.