Portrait by Benjamin McMahon for Elephant

This profile was first published in Elephant Issue 40

It’s raining when I meet Anthea Hamilton at her South London studio, and I arrive damp from the grey, drizzly walk from the tube. Waiting for me inside, she is dry but slightly worse for wear, having attended the opening of a new store for fashion house Loewe on Bond Street the previous evening. “I hardly ever go to things like that!” she says, laughing. Leaning on one elbow, she is tired but welcoming, elegantly dressed in a long shirt and white trousers. Fabric samples and second-hand books line shelves across one wall, while a collection of toy and ceramic pumpkins sit beneath a window. It has been a busy year for Hamilton, with her first exhibition, The Prude, at her new gallery Thomas Dane in London’s Mayfair under her belt, and her recent inclusion in the fifty-eighth Venice Biennale, curated by Ralph Rugoff.

Many will recall her inclusion in the 2016 Turner Prize show, a sixteen-foot-tall pair of buttocks emerging from a brick wall at Tate Britain. “I woke up in the night halfway through the planning and thought, what have I done? I’ve agreed to make a bum for the Turner Prize! Make my headstone now: ‘Bum Artist’,” Hamilton candidly chuckles. “I had to ask myself, what can I do to not make it all that this experience is?” She needn’t have worried, returning as she did to the gallery two years later for their prestigious annual Tate Commission, this time with an immersive installation inspired by a found photograph of a man dressed as a vegetable. Performers moved through the space dressed in costumes designed in collaboration with Jonathan Anderson, creative director of Loewe. Set in a sterile, white-tiled space, the show became one of the most photographed events of the summer. It is fair to say that Hamilton has successfully refused easy categorization.

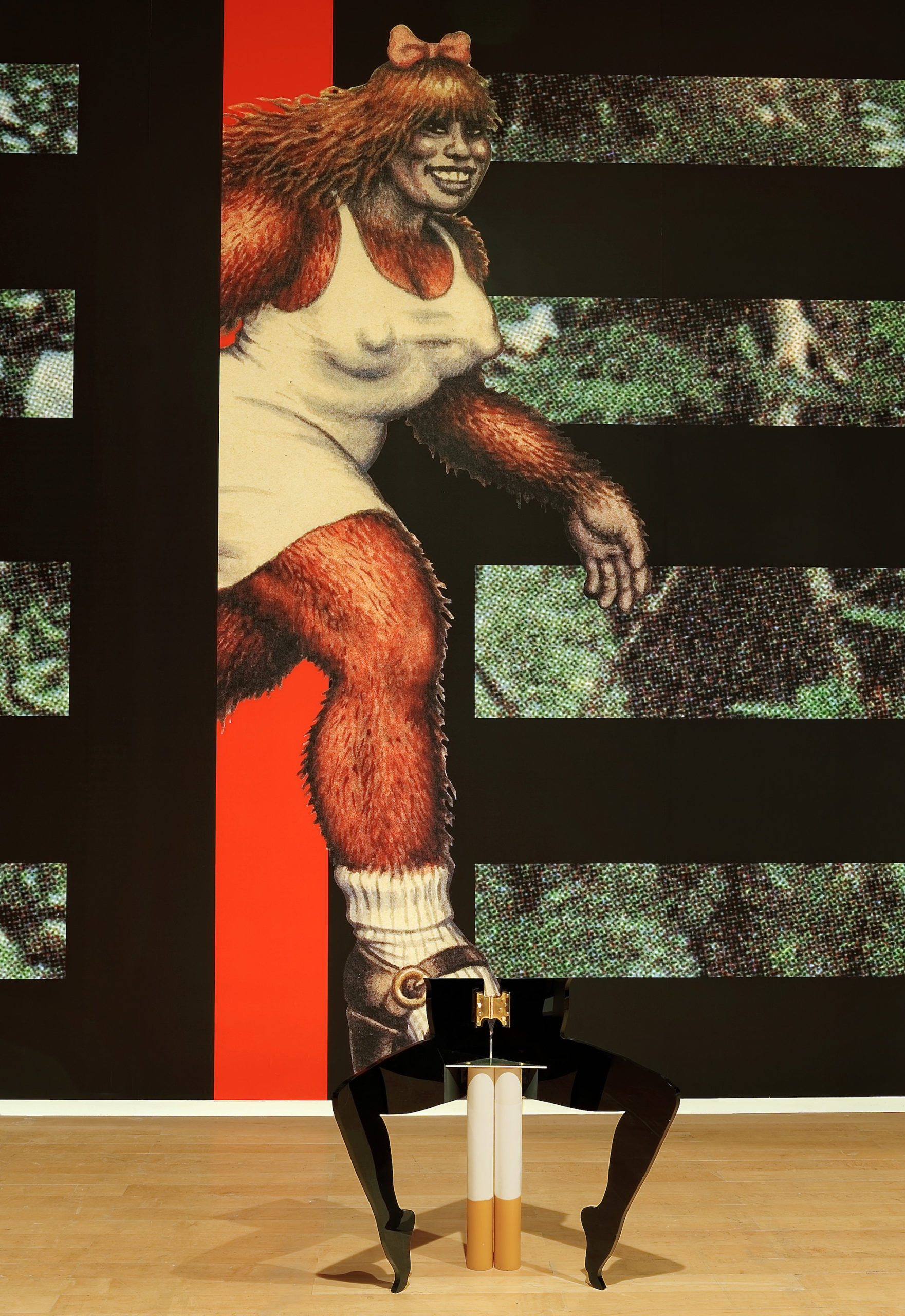

Lichen! Libido! Chastity! Installation view, Sculpture Center, 2015

“I follow my gut with my brain and my body. I find that the computer doesn’t necessarily allow my brain to open up”

Instead, what unites Hamilton’s varied installations is their freewheeling assortment of disparate references, be that 1970s disco or mid-century interior design. The “bum” at Tate, titled Project for a Door (After Gaetano Pesce), was inspired by a photograph of an unrealized model for a doorway by Italian designer Gaetano Pesce. The multi-layered research behind her work, whether she’s exploring a single image or the feel of a certain fabric or object, is derived from personal intuition, as well as a certain curiosity about the world. “What I do is this process of somehow following my gut with my brain and my body. I find that the computer doesn’t necessarily allow my brain to open up. It’s about switching modes of thinking, and maybe that’s what research is for me, that you go into a mode of deep receptivity where anything and everything can be an input,” she reflects.

Hamilton grew up in a mixed-race family in South London in the 1980s, a stone’s throw from where her studio is situated today. “To grow up in London, in a space which is diverse in every sense of the word, meant that I didn’t have to question (to as much of a degree) the idea of being a minority,” she remembers. “Growing up here, I always felt like I could be whoever I wanted to be.” It was only when she moved to the north of England to study in Leeds as an undergraduate that she became more aware of the freedoms of London. “Suddenly, all the people that I was used to seeing on the street back home just weren’t there, or they were in much smaller communities. It seemed more ghettoized.”

Leg Chair (Sushi Nori), 2012

Upon her return to London, she didn’t picture herself as an artist at first. “I didn’t know that being an artist was something that someone could do. The image of an artist was someone like Toulouse-Lautrec… you don’t realize that it could be a reality. Definitely not how I grew up,” she recalls. “I think I realized I was quite an artistic person, which is different from being an artist.” Interior design and film were another avenues that Hamilton considered; she tells me that she ran a project space, as well as working at the Arts Council for a period. “As time went on, those options eroded because I wasn’t as good at them. It was a process of elimination, in a way.” She recalls how she used to visit flea markets religiously, particularly during a year living in Paris—“I guess that really trained my eye in how every object reads.”

Hamilton returned to the Royal College of Art to study painting in 2005, where she was able to give herself the time to research. “I used to go to the RCA library a lot, but I feel a little disillusioned about what libraries are now,” she says. “Which books, due to popularity, are still present on the shelves, and which books have been taken out of circulation? Which things never got a chance to be on the shelf? I’m aware that there’s more information left out of a library than there is in there.” In her expansive work, she interrogates the politics of how we look at the world, tugging at the threads that hold together the hierarchies that we place on the images and words that surround us. “I try to teach myself how I look at things, and how that looking has been informed, and how other people might look at things.”

“I didn’t know that being an artist was something that someone could do. The image of an artist was someone like Toulouse-Lautrec…”

- The Prude, Thomas Dane Gallery, 2019. Installation View

These carefully traced thought processes are behind everything from Hamilton’s “reimagining” in 2016 of the Kettle’s Yard House in Cambridge to her exhibition at Thomas Dane earlier this year, for which she covered one wood-panelled room with fake fur in brash shades of pink and yellow. The effect reminds me of a giant Battenburg cake, but she explains, “I was actually thinking about the space of the gallery. It’s quite precious, and it’s old, and it’s definitely Mayfair. I always question, what am I doing in that space? Am I there for good or for bad? I wanted to change the terms of it, so I put something cheap like fake fur on the walls. I thought, people are going to want to touch it, which is nice. And then there’s another layer of associations with 1960s interiors, really decadent…”

With that, we spiral into an excited discussion on elaborate, David Hicks-style interiors, of the kind where the curtains match the wallpaper, and Hamilton namechecks a radical Milan-based designer in her eighties, Nanda Vigo, who designed highly tactile living spaces. “I can really go into expanded details on these things, but it’s also fine if people want to come in and just touch the wall a bit,” she adds. “It’s about offering people different entry points. Does that bring in a discussion about empathy? Maybe it didn’t when I started, but a conversation about empathy became more prevalent, and it gave me a language to think it through.”

Wavy Alabaster Boot, 2016. Installation view, The Turner Prize, Tate Britain

“I think excitement is important. I want people to be stimulated, physically and mentally, and on their own terms”

A repeated motif in Hamilton’s installations has been a series of high-heeled, cartoon-like wavy boots, rendered in materials ranging from Perspex to alabaster. Legs also recur, with feet pointed, a cut-up interpretation of the female form, as if poised to slide directly into the boots. “The body that most often is in the work is my body. Maybe it goes back to that thing of empathy again. I would draw around my leg and make these templates. They’re me, but not me,” she explains. These disembodied legs often protrude from the walls as if in motion, at once uncanny and firmly human; they add a sense of theatricality to proceedings, like props in an elaborate stage set, poised to suddenly kick and strut.

From faux-fur to wavy boots and performers dressed as vegetables, Anthea Hamilton continues to confound. We leaf through some of the books on her shelf, including a brilliantly silly John Travolta workout tome from 1984, each of which give some grounding to the multiplicity of her work and how it can be read. At turns playful, inviting, confronting and surprising, what does she hope people will experience when they encounter her work? “I think excitement is important. I want people to be stimulated, physically and mentally, and on their own terms.”

This article first appeared in Elephant Issue 40 in Autumn 2019

BUY NOW