Antonio Roberts doesn’t like being told what to do by big corporations with clever lawyers. A proponent of free culture, the Birmingham-based glitch artist explores notions of ownership and copyright—often by testing the limits of the latter. Text: Molly Taylor.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 27.

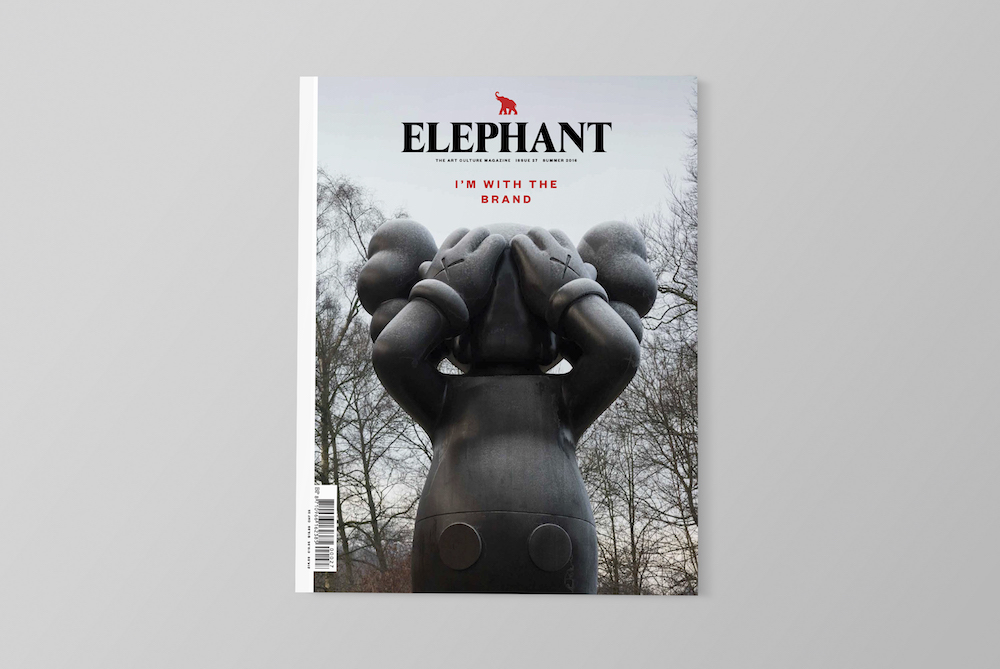

Though much of the content in your jarring, audiovisually avant-garde work Transformative Use, included in Jerwood Visual Arts’ recent group exhibition Common Property, is glitched beyond recognition, there’s one part of the artwork where Mickey Mouse’s face is very clear. How do potential breaches of copyright like this go down with brands like Disney?

In the lead-up to the exhibition all the artists involved had to have a conversation with a lawyer who’d looked over the proposals, mainly so that the Jerwood Space didn’t get in trouble for commissioning the works. I didn’t want to get in trouble either, but I also don’t like the current copyright laws and I want to induce change; to promote free culture. I think if I was to operate inside the law then the message would be: look, everything’s working just fine.

How is copyright affecting the way that artists are able to create and distribute works that remix or reuse images belonging to other people, particularly brands?

I’m not against copyright, I just think it reaches too far. For smaller artists, other people appropriating their work isn’t so much of a problem because if you’re not making much money, you haven’t got much to lose. Whereas for the larger corporations like Disney, they see it as losing them potentially millions and millions of pounds. So I chose Disney for the Transformative Use piece because they have really lobbied to get copyright terms extended in their favour.

Do you feel at all warmly towards Disney or characters like Mickey Mouse? The work seems to be a homage to them in a way.

I was brought up with Disney, like I’m sure most of our generation were. My favourite films were Aladdin, Toy Story and The Little Mermaid, and they were a big part of my life when I was younger. It’s a shame that appropriation is such a one-way system: Disney are happy to promote their works endlessly and make everyone want to pay to go and see their films, but as soon as those same people want to use something they’ve made creatively, they say no. It’s similar to urban brands like Nike that associate themselves with street culture: the style of that community is appropriated by the corporation, copyrighted and then sold back to those communities. But people living in inner-city areas often don’t have the money to afford those types of clothes.

How real is the threat of legal action for you and for others engaging in this type of practice?

It’s a real threat. I jokingly say that I want to get myself sued because the media coverage would be amazing… It hasn’t happened to anyone that I know yet, but when you become a bigger artist it does become a problem. The law changed in 2014 to keep up with internet culture and allow appropriation if it’s a parody. But Luc Tuymans recently lost a plagiarism case despite arguing it was a parody. The Beastie Boys are currently being sued for their use of sampling in Paul’s Boutique (1989). Then you have dj Shadow, a huge figure in the hip-hop community whose first album was made pretty much entirely out of samples, and the copyright holders asked for tens of thousands of dollars just to use each one. Each song contains ten to 20 samples, and there’s 13 songs on the album. So you can do the maths: it’s a lot of money. And ‘losing’ that money is what the corporations are angry about. To address that, one of the founders of The Pirate Bay [Peter Sunde] made a great art piece which just copies a Gnarls Barkley song over and over again, endlessly. He has a counter that racks up the amount of money being ‘lost’, but really it’s a statement about how that money is just theoretical.

Your Copyright Atrophy works consisted of a series of GIFs showing brand logos—Nike, VISA, Virgin, YouTube, XBOX, Taco Bell—dissolving into abstraction.

Copyright Atrophy was a protest piece. I wanted to show that, for the most part, these brand logos are just lines and curves and bits of colour. They have no real meaning beyond what is sold to us using huge marketing budgets. Take the Nike swoosh: it’s just a tick. It’s just a piece of clothing with an emblem on it. For my solo exhibition Permission Taken, which showed at Birmingham Open Media and then at the University of Birmingham earlier this year, I cut out a load of logos with my vinyl cutter and hid them within the piece. I show viewers: here’s a Playboy Bunny, here’s a fila logo. But people often can’t see them. Then others will point out logos that I didn’t even include in the artwork and yet the way the colour overlaps evokes the sense of a brand for them. Brand logos are pervasive: we expect to see all these logos everywhere. It’s weird when we don’t.

Are you trying to antagonize the brands when you use their logos in work like this?

I want to antagonize the law-makers who protect the brands. I want things to change. I don’t want the people who have the money and the power to dictate how people can create stuff. It’s just not right. If that means I have to be held up as an example—even though I’d rather not, I’d rather have a safe and healthy life—then fair enough. I’ll make a point of it.