Reporting From the Front stirs up images of danger, patriotism and national interest, and is a fitting proposition for 2016’s Architecture Biennale in Venice. As the UK finds itself in the grip of a housing crisis–we’re certainly not alone in this–three British curators, Jack Self, Shumi Bose and Finn Williams, create Home Economics; an architectural response to the current climate. The Biennale opens to the public on Saturday 28 May.

Can you briefly describe your response to the idea: ‘Reporting from the Front’?

Jack Self: Alejandro Aravena has executed quite an ideological shift with this theme. He is not asking ‘What is the front line of architecture?’ but rather, ‘What is the front line of social struggle in your country, and what can architecture do about it?’ Coincidentally, the extreme housing shortage in the UK–which is driving social inequality, exploitation through rent and oppression through debt–could be seen as our most pressing concern. In order to address this crisis, normally understood exclusively in economic and political terms, Home Economics proposes an expansion of the role of the architect in order to more effectively harness their skill and agency.

Do you feel that your response is purely British, or does it confront a more universal problem for modern living?

Shumi Bose: The problems–or rather, conditions, as we’re not really framing these as problems and solutions–described in the five proposals are global, if not universal. Whether discussing unaffordable living costs, the changing nature of family life, or the treatment of dwellings as assets rather than homes, many of the situations we frame are a symptom of globalised markets and late capitalism; we have now presented the ideas within Home Economics from Rotterdam to Rio, and we have found that these ideas resonate with various audiences. Also the lens of time, which we selected as a universally pressurised factor affecting contemporary life–we figured that everyone could relate to the idea that life is measured in beats and units of time.

Yet, there is a peculiar and rather unique relationship that Britons have towards the notion of ‘home’. Particularly with regards to ownership; the aspiration and idealism behind the privately owned dwelling has a very British anxiety and idealism associated with it. A man’s (or woman’s!) home is his castle, desirable above all, and is therefore a repository for hopes and dreams; it is also the place where, through material and spatial choices, he or she would embody their ideas of class, taste, cultural values, power and gender relations. In France, the idea of long-term rent is less stigmatised than it is in Britain; in Switzerland social housing is for all income levels, and in Germany collective ownership is relatively common. So there are some attitudes embedded in the show that reflect a very British attitude to the idea of home.

You’ve mentioned that the British housing crisis is due, in part, to the ‘failure of traditional housing models to accommodate new patterns of domestic life.’ Do you feel this has been a constant and ongoing area of difficulty for architecture; or is it a more 21st century problem?

JS: Every epoch has its own specific crises to address, inasmuch as every generation creates and recreates their own reality. We shouldn’t claim any unique status of the present day. However, the biggest change concerns the rise of mass mobility. There are many causes of this, including the economic and political. But probably more importantly for Britain, mass mobility has been the result of inexpensive air travel, the EU right to free movement and the proliferation of universal real-time communications (mobile and internet). These factors have stretched and compressed our experience of space, which has fundamentally restructured our relationship with time. We must still ask ‘where do you live?’ but we must also add, ‘and how long will you live there?’

You’ve chosen to work with people who can offer an alternative to the traditional models of architecture. Do you feel that architecture must now look outside of itself to work its way through the current crisis?

SB: Architecture as a traditional vocation has changed immensely, both in its culture but also in its practice, through technological and other developments, like attitudes towards risk. Many roles traditionally located within the architect’s office have dispersed outwards, to more specialised practices or technical contractors. But architectural thinking, as a design process is incredibly powerful; there are ways in which its structural and collaborative processes may be applied to many other fields. It’s not strictly a case of designing buildings, which I think architects will continue to do of course–but in terms of an impact on space and affecting the way we live, we would argue that something like Uber constitutes some architectural, and obviously urbanistic, thinking. We would agree, however, that in the current economic context, it would be of great value if architects consciously had a better understanding of financial and political issues, whether in traditional practice or not. We find it frankly irresponsible, for example, that the realities of viability and other real financial pressures are hardly discussed in the academy, during years of architectural training.

Of the five propositions included in the British Pavilion, you will be focussing on ‘hours’–as opposed to days, months, years and decades. How are hours addressed in the work?

JS: The time period of hours is a tricky one. It would seem self-evident that we spend hours in our homes. So the intent was to imagine a type of domestic space offered in addition to the individual residence. The proposal is for a communal living room. Access is private, yet it is offered as a kind of extra social space adjacent to the home. It is imagined within the context of a new model of a high rise social housing tower, where the traditional relationship between core, corridor and unit has been broken down–the core has been pulled apart to create these spaces between apartments.

In the show itself this common living room has been realised at 1:1 so that it can be directly experienced. It demonstrates how, if we are prepared to share rather than insisting on individual ownership, we can all have a better quality of life and space. In other words, it demonstrates sharing as a form of luxury, not compromise.

Did you work closely with the four other teams, or have the five rooms been developed quite independently?

SB: We started this process with a weekend workshop involving all the collaborators–participants, exhibition designers, industry advisers all in the same room, sharing ideas, questions and meals. This was a really important moment in exposing and developing our thoughts–there was plenty of cross-pollination, and it was very good to share initial ideas so that each team could position themselves with more acuity and conviction. It also allowed our industry advisers to form natural partnerships, or provide specific expertise as necessary. For example, Naked House Community Builders and our invited participant Julia King formed a close affinity, and effectively co-authored a proposal, whereas others preferred to follow their own artistic or creative practice.

Following the workshop, we developed an overall brief, with specific and detailed sections for each team. As curators, we worked through many variations and iterations with each team individually, sometimes remotely but with close attention. But we have all been working from a shared Dropbox, so everyone has been able to check on what their colleagues are doing and producing. From the beginning we intended to have an open structure, where we can see and benefit from the others’ thinking.

There is an emphasis on architectural responses, rather than solutions, throughout the project. Why is this important?

Finn Williams: We think it would be misleading to claim that architecture itself can ‘solve’ the housing crisis. The underlying causes of the crisis we currently face in the UK are longstanding, systemic, and complex, so proposing a particularly clever flat layout or self-build system as a solution would almost distract from the larger social, economic and political challenges that architects should also be turning their attention and skills to. We believe architects can have an important role in responding to these wider challenges, but not necessarily by always proposing a building as the answer. For example, Home Economics shows that architects can help to redesign debt, as Julia King has done in the Years space by developing a new kind of mortgage together with a housing association and high street bank. Or they can redefine what we understand as rent, as Dogma and Black Square have done in the Months space. For us, these responses aren’t so much readymade solutions as models that can be adopted, adapted and realised in different ways.

Paolo Baratta suggested that architecture is the most political of all the arts, would you agree?

FW: No art can be immune to politics–particularly if money is involved. But architecture does take more money, and more time, than most other creative disciplines. It also usually involves a level of public permission through the planning system. And of course the politics of architecture don’t stop when a building is complete, political life is played out within architecture. So if politics is an unavoidable part of the way architecture is funded, permitted, and occupied, it should also be an integral part of the way we learn and practice architecture. Home Economics suggests that architects need to see politics (and economics) as part of the design process, if we really want to influence the built environment.

The 15th International Architecture Exhibition, ‘REPORTING FROM THE FRONT’ runs 28 May until 27 November at various venues. The exhibition ‘Home Economics’ has been commissioned by the British Council for the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2016.

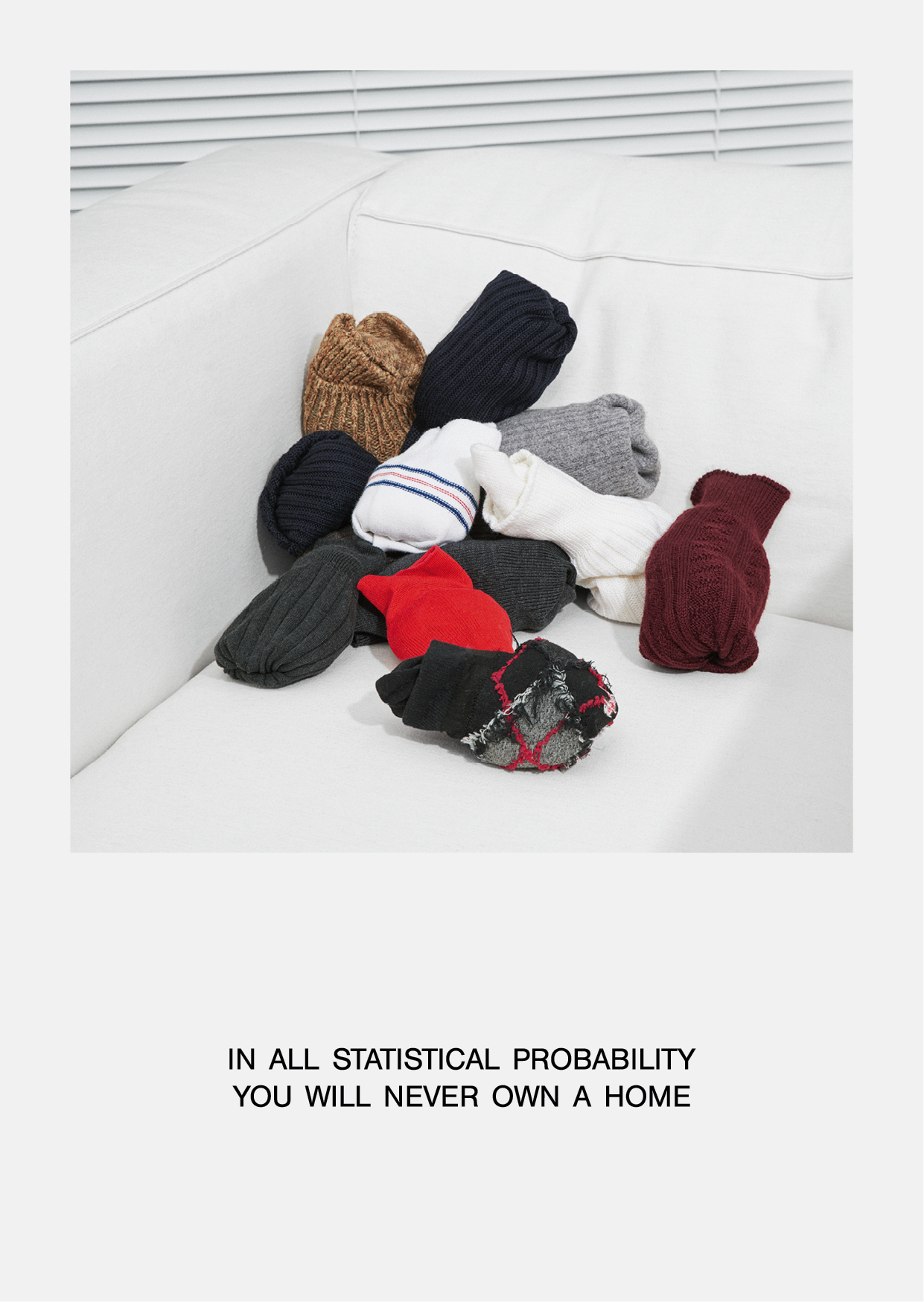

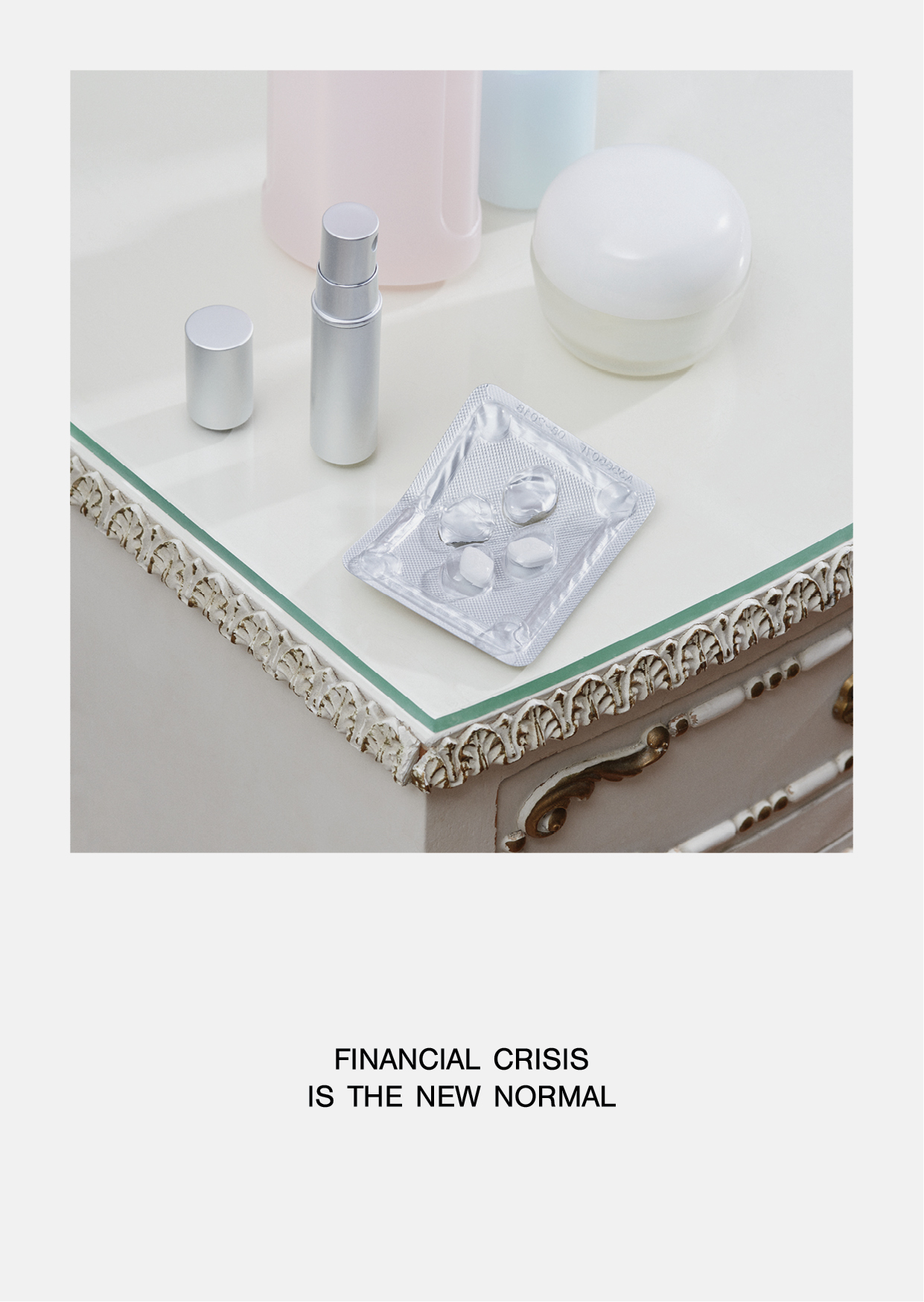

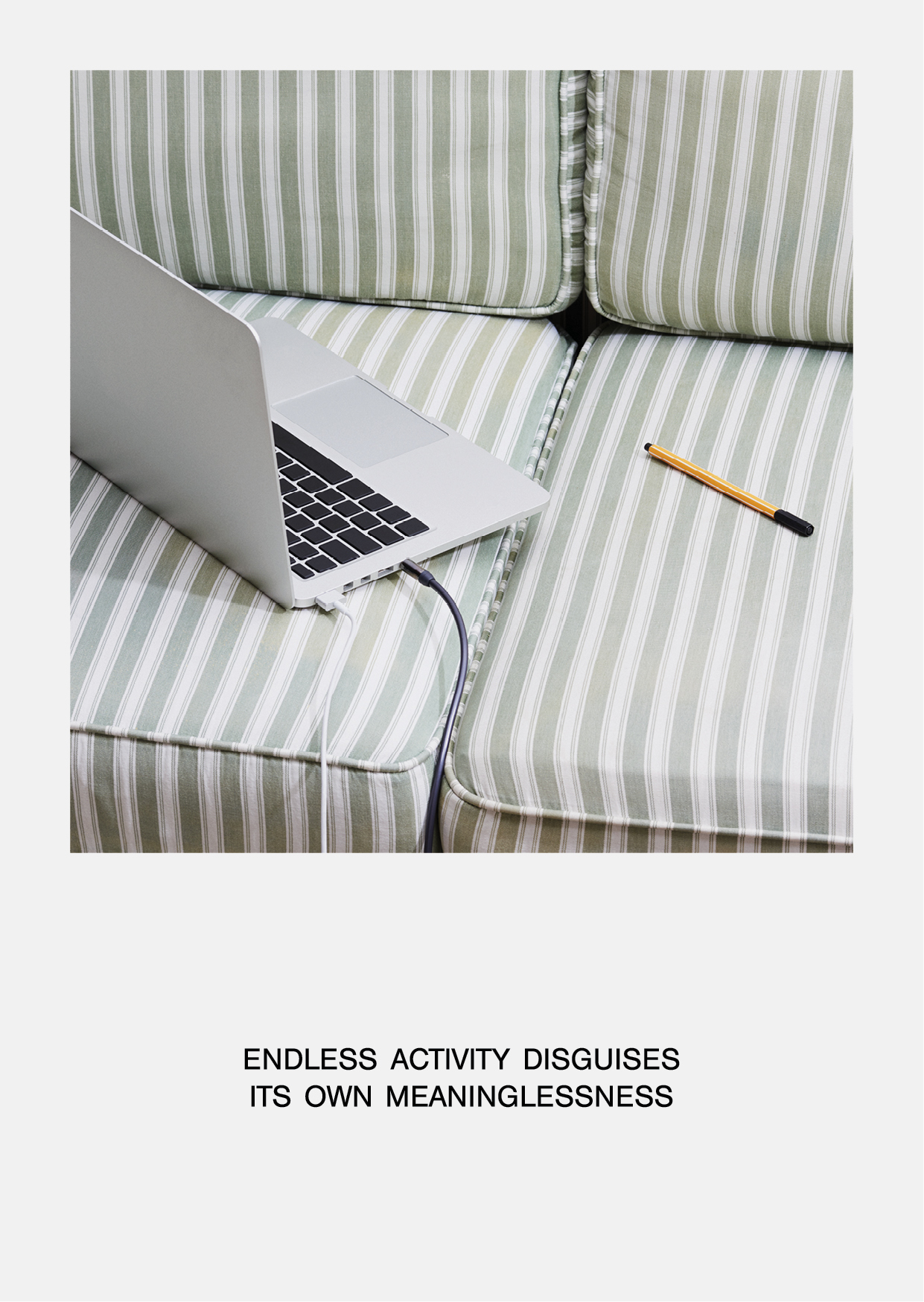

Home Economics #7, 210×297mm, OK-RM and Matthieu Lavanchy, 2016