The Armory Show’s Focus series brings together gallery presentations, organized under the guidance of an annually appointed curator, with new or rarely seen works. This year, the section is led by Gabriel Ritter and focuses on technology’s impact in the quotidian sphere. Titled Body Mediated by Technology, the theme is reflective of our post-internet age of online hyper-consumption. I expect to see, as is the norm at most art fairs, people walking around with their phones continuously taking images, perpetually documenting their existence at the art fair and boosting their cultural currency. Instead, I am first presented with most devices hidden from view and special attention paid to the Focus series. The irony would not have been lost on many—there’s something to art speaking of technology that both shames and alerts you to your own dependence.

Still, I find fairgoers on headphones and video-chatting while navigating my way further through the fair. I dodge the plethora of iPhones out to image capture, afraid of ruining their money shots. It seems that the allure of the screen is hard to resist. It’s hard to deny art imitating life and vice-versa in this regard: the literal mediation of art consumption and observation through personal technology is fully evident. The Focus theme comes uncomfortably close to life. Are these fairgoers part of a performance, or is this our reality? It is interesting to observe what becomes of this omnipresent mediation and the potential manipulations of this system, as shown through various works in the Focus series.

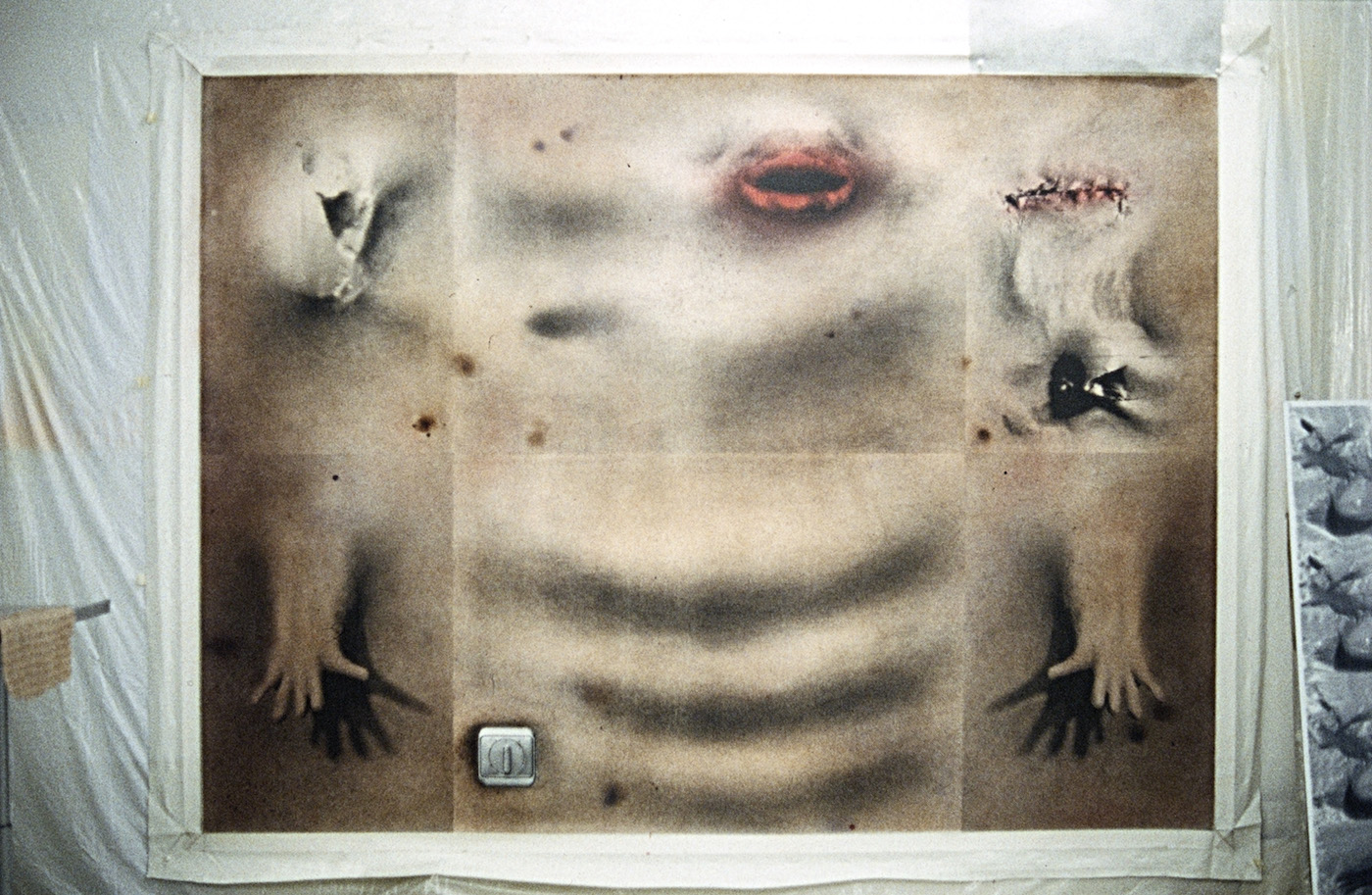

At Empty Gallery I am confronted with pink blobs, eerily recognizable as body parts on a machine-like contraption. The sculpture, Virtual Form

(1990) by Tishan Hsu, teeters on the grotesque but with a clinical tone rendering body and machine indiscernible. The Chinese-American artist’s works explore the effects of technology on the body, particularly where tangible and more abstract virtual elements occupy the same dimension simultaneously. This rings true at a time when offline and online have become archaic terms, with technology playing a central role in daily life.

“Are these fairgoers part of a performance, or is this our reality?”

Ironically enough, going back into the Hong Kong gallery’s space to take another peek at the newly-repaired sculpture, I am confronted with someone scrolling through their phone while in front of one of Hsu’s dysmorphic prints. Standing as if examining the work, the pseudo-observer continued to bring his phone to his face to take a closer peek at his screen. Perhaps this performance perfectly expressed Hsu’s exploration of technology’s relationship to ourselves: rather than functioning as some outer extension, it has far-reaching implications so deep that it envelops us entirely. Today, scratching one’s head while observing a painting is as natural as reading the latest social updates on one’s device.

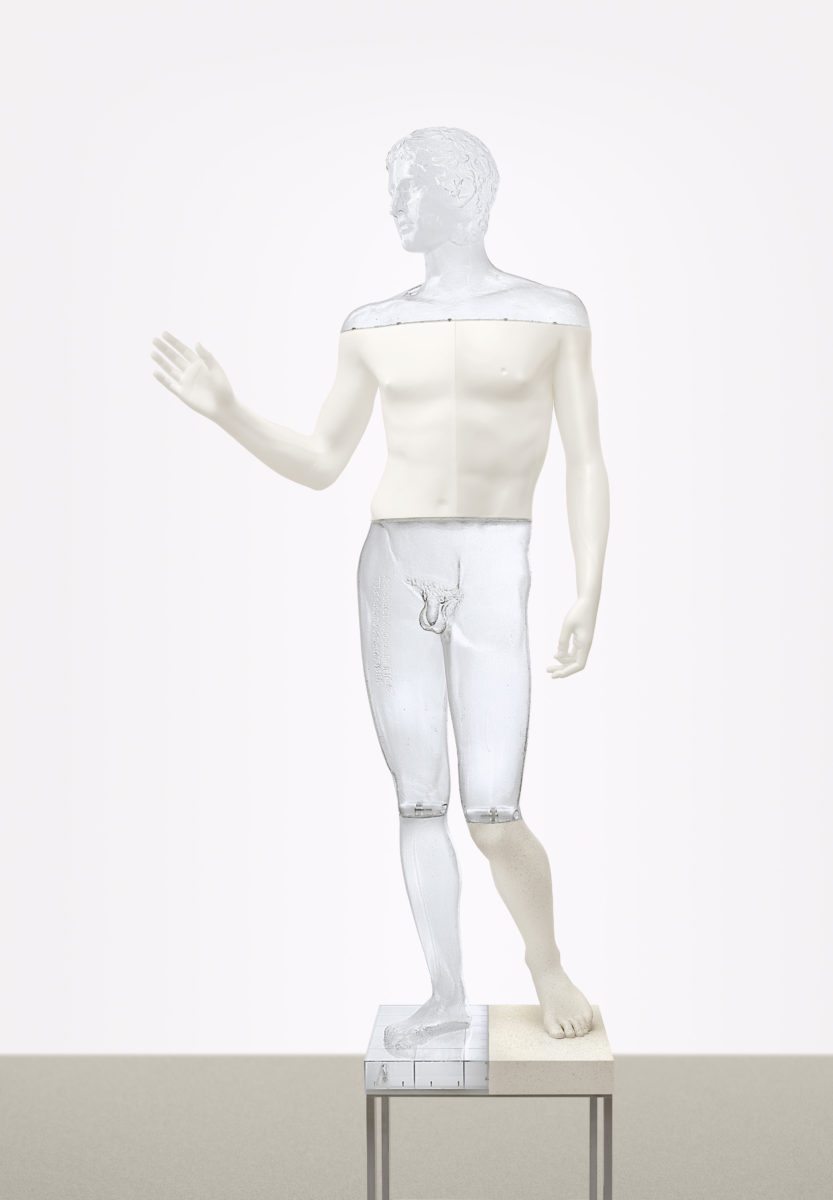

- Oliver Laric, Jüngling vom Magdalensberg, 2018. Courtesy Tanya Leighton, Berlin

Further along, Berlin-based Tanya Leighton have included in their booth works by Oliver Laric, notably Jüngling vom Magdalensberg (2018). Themes of reproduction, authenticity and appropriation come to surface with the large-scale depiction of the only ancient full-size bronze statue in Austria. I walk around Laric’s reproduction of the original statue, examining the layers of different materials with varying degrees of hollowness.

There’s a conscious cheekiness to Laric’s appropriation paired with this stress on accessibility. This is especially evident on his website, threedscans.com, where anyone can get a 3D model of the artist’s works—albeit on a much smaller, simpler scale. Are these reproductions our new cultural artefacts with the potential for infinite variations of the same model? Laric’s digitization of classicism, rather than simply reproducing the same exclusive Western arts ethos, questions its existence within a contemporary post-humanist context.

Pareidolia is a term for seeing patterns in random configurations, such as spying an image of a dog in the clouds; playing on this term is Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Pareidolium at Max Estrella. In the centre of the gallery’s space, the low, circular pool draws in the curious with vapour continuously rising and a pair of footprints outlined at a particular spot around it. Planting my feet within the outlines, I momentarily see something akin to my face come out of the computer-controlled ultrasonic atomizers in the form of water vapor. I double take, and just like that it is gone into the void. I look around, wondering if anyone recognized me in the pool, questioning my level of sanity and fatigue at this point in the fair, but I soon learn that this is a face detection system.

Paraeidolium, much like the rest of Hemmer’s practice, is highly interactive––to the point that his installations do not exist without this interaction of the spectator’s body. The mediation between technology and body here become uniquely entwined. I move on, my own everyday relationship to technology set in a new light. Before long though, I am charging my phone once again at the fair, not failing to add my own contribution to the Focus series theme.