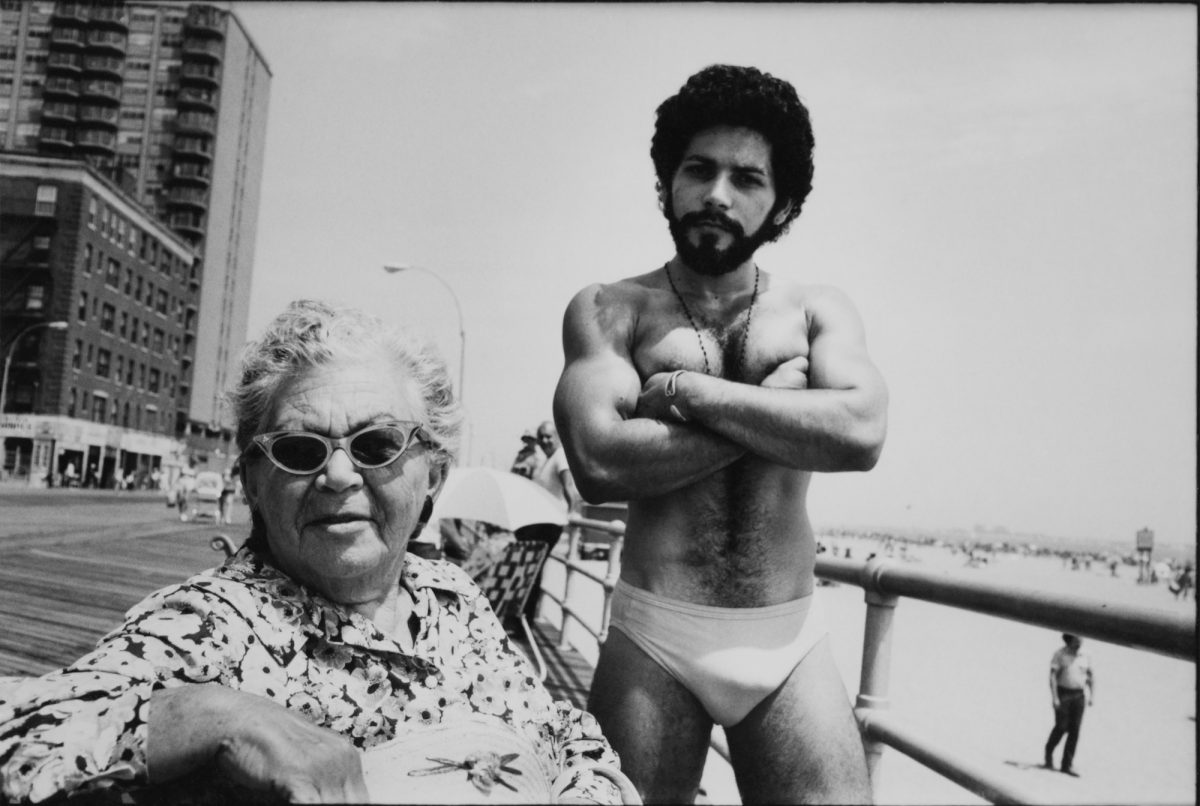

It has been five years since the death of Arlene Gottfried, a legendary street photographer who tirelessly documented the lives of New Yorkers. She turned her camera on everyone from the Puerto Rican community of the Lower East Side to the eccentric locals of Coney Island.

At the time of her death, she left behind an immense archive of 15,000 prints: an eclectic body of work spanning four decades, much of which has never been exhibited publicly. Two current exhibitions offer some corrective, bringing Gottfried’s contributions to photography into sharp focus, at the Cobra Museum of Art in The Netherlands and Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York.

While each exhibition focuses on a different series of work, they equally bring to the fore Gottfried’s unique handling of her subjects. Her empathy and deft eye for human stories distinguishes her from her contemporaries, cementing her place within the history of photography.

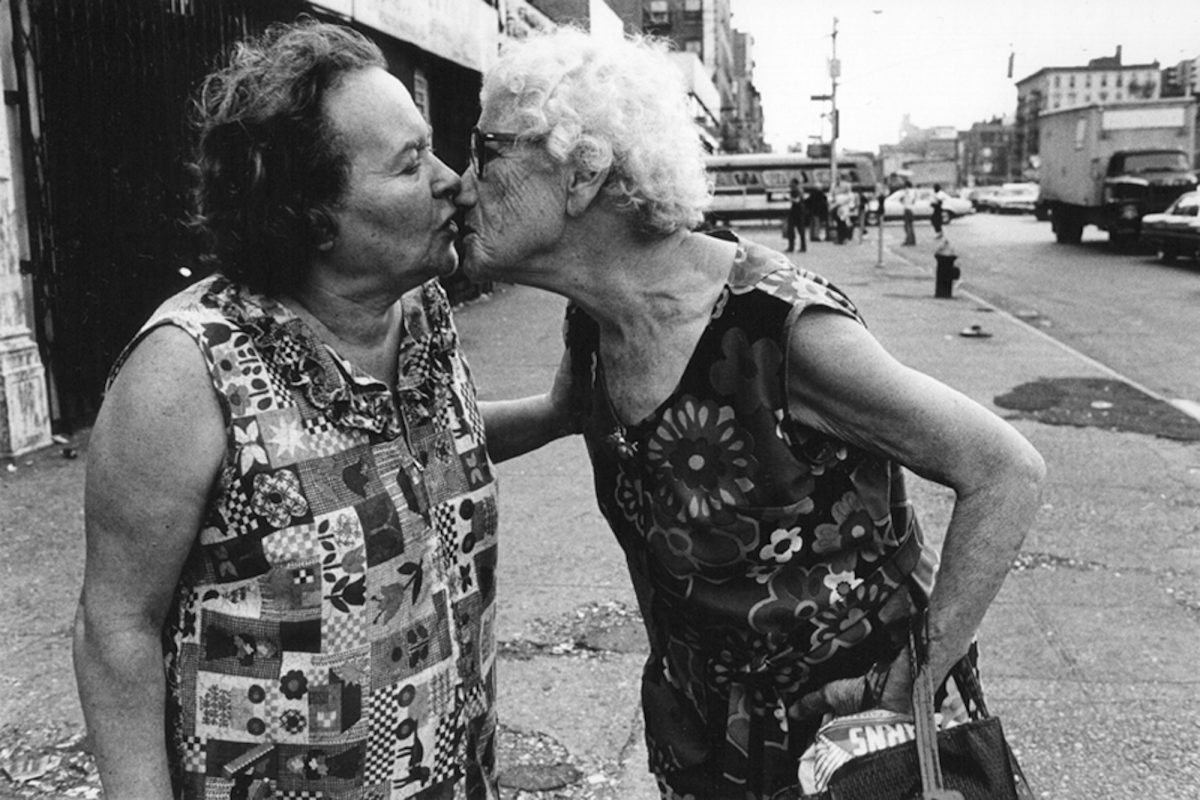

Born in 1950 to a Jewish family, Gottfried’s early childhood was spent living above her family’s hardware store in Coney Island, where she encountered “an exposure to all kinds of people”. Although described as shy or modest by those who knew her, Gottfried always demonstrated a curiosity and willingness to approach strangers: “I never had trouble walking up to people and asking to take their picture,” she told The Guardian in 2014.

The family moved to Crown Heights in Brooklyn, an impoverished neighbourhood with an expanding demographic of Black and Hasidic Jews. As a teenager her father gifted her an old 35mm camera, a formative introduction to photography.

“Gottfried positioned herself and her camera amongst communities, indicating that she felt herself to be one of them”

This early exposure eventually led her to enrol at the Fashion Institute of Technology in the late 1960s. Although she was the only woman in her class, the gender imbalance didn’t dampen her ambitions. As Daniel Cooney, her gallerist and friend tells me, “Arlene wasn’t the type to dwell on her challenges.”

She took her first photographs at Woodstock in 1969, admitting in 2014 that she had “no clue what I was doing”. But the experience of documenting a watershed cultural moment “hooked” her to photography. In 1972 she moved to Greenwich Village and lived in the heart of New York’s seismic identity shift, a time of flourishing youth and counterculture.

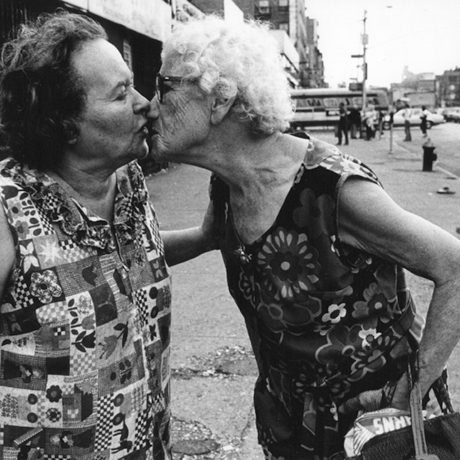

- Left: Mommie and Bubbie Kissing. © Arlene Gottfried and Daniel Cooney Fine Art

- Right: Angel and Woman on Boardwalk, Brighton Beach, 1976

She became a wanderer of the city, taking unflinching photographs of a now bygone era: a pre-gentrified and pre-financialised New York. She mingled amongst the regulars at Studio 54, the heroin addicts, rebels, and Stonewall activists like Marsha P Johnson. To earn a living, she found work with an advertising agency, contributing to the likes of The New York Times Magazine, LIFE, and Newsweek.

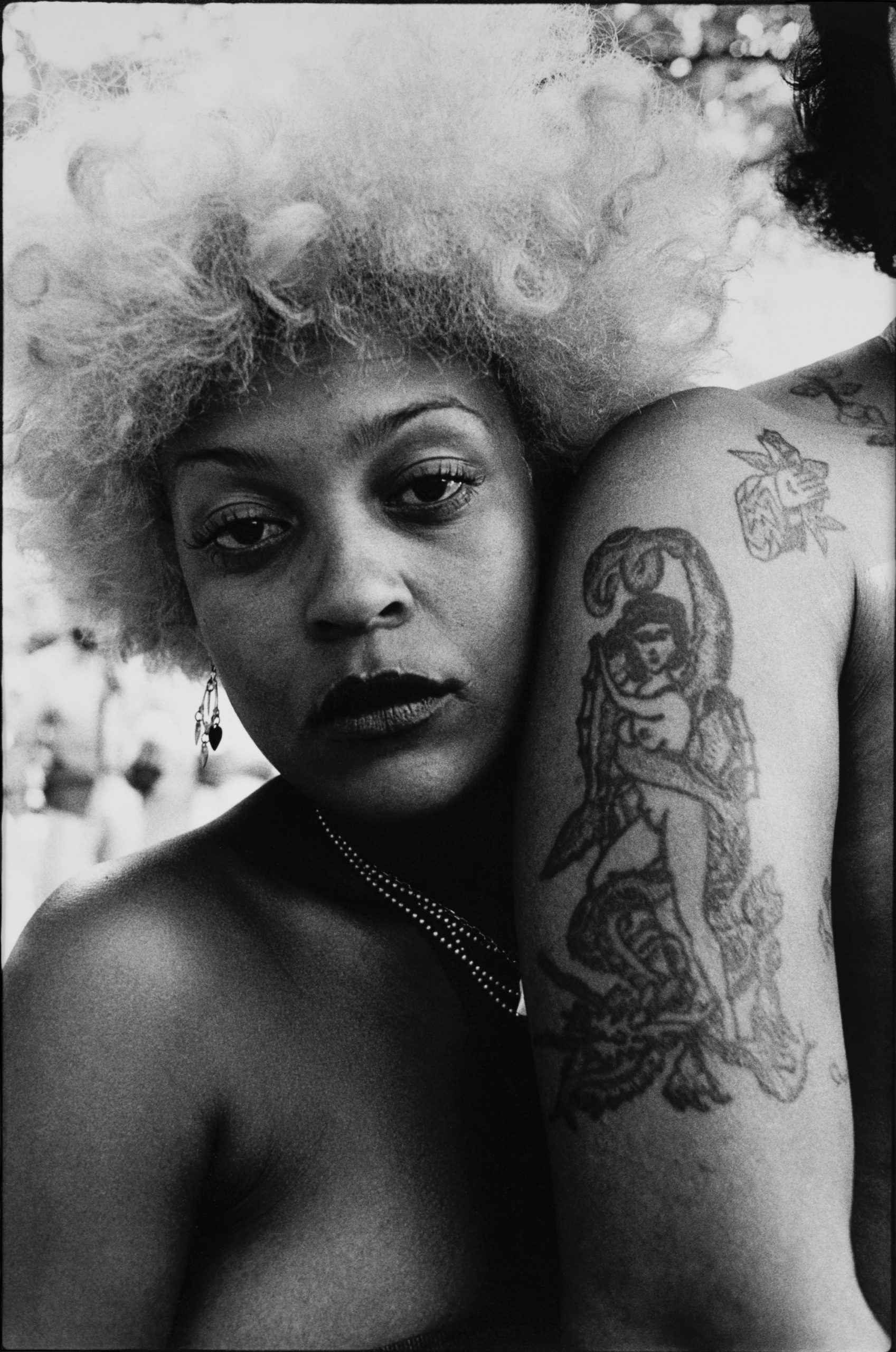

Clandestine at the Cobra Museum of Modern of Art situates Gottfried’s work alongside legendary photographers known for their provocative framing of the human body: Robert Mapplethorpe, Helmut Newton and Diane Arbus.

Comparisons have often been made between Gottfried and Arbus, though their approach to their subjects distinguishes them. As Susan Sontag observed, Arbus concentrated on “the victims, on the unfortunate, but without the compassionate purpose that such a project is expected to serve.”

In contrast, Gottfried positioned herself and her camera amongst communities, indicating that she felt herself to be one of them. After all, they were her neighbours. “Her spiritual presence was strong, although she was not a boisterous person,” Cooney tells me. “I think that was her secret in making people comfortable to be photographed.”

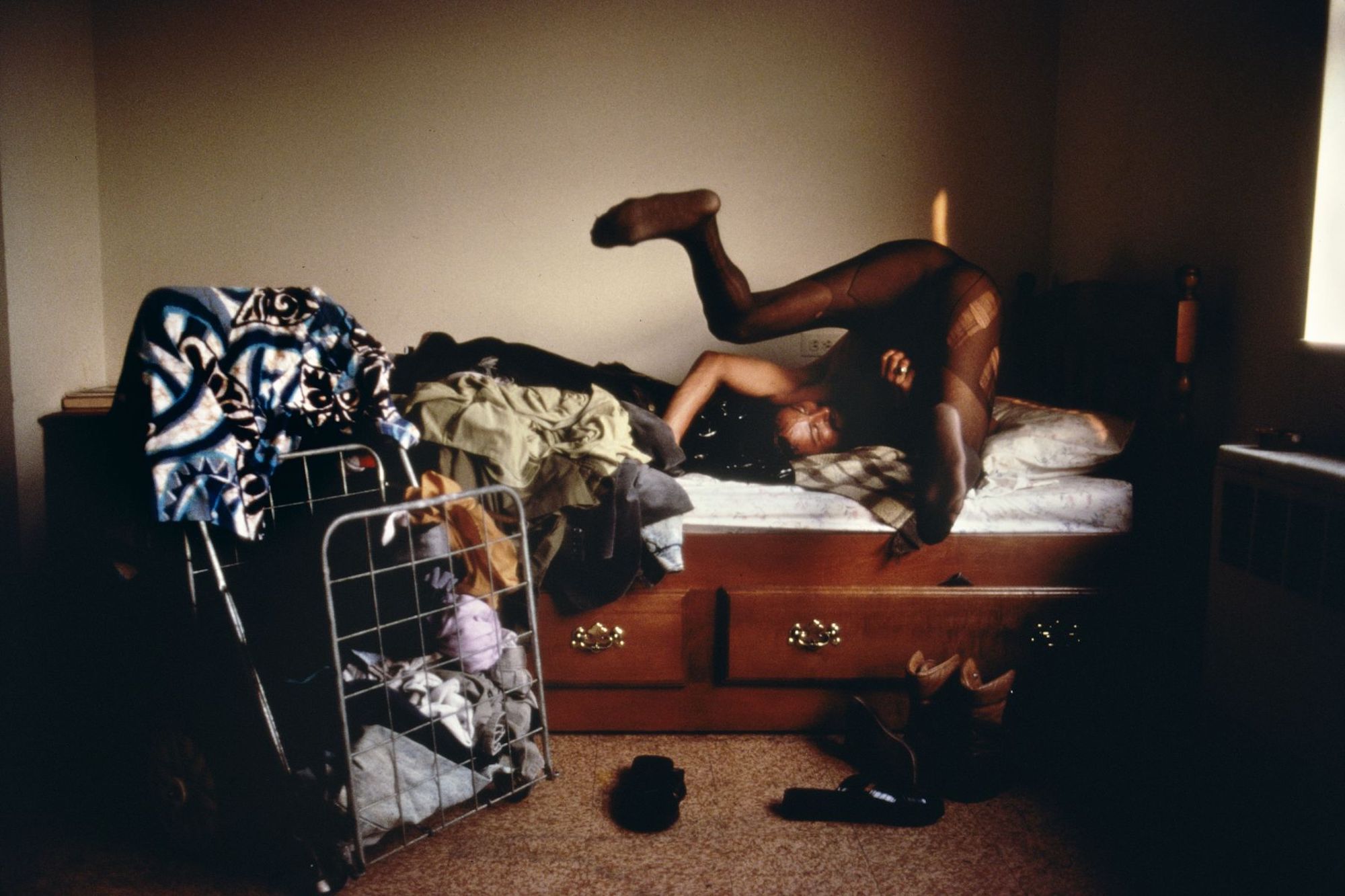

Gottfried’s ability to have meaningful connections with her subjects is captured in Midnight, an exhibition of the titular series currently on show at Daniel Cooney Fine Art. Midnight was a man Gottfried befriended in the summer of 1984.

“The tenderness between artist and subject underpins Midnight, but is accompanied by a critique of the health and social care system”

“Handsome, friendly, and fun to be with, Midnight invited me to an underground Lower East Side club where he was performing a dance to the beat of drums and the poetry of Miguel Algarín and Miguel Piñero,” she remembered. Midnight led a life of wild, uninhibited and youthful abandon, and quickly became Gottfried’s muse. She would spend the next two decades photographing him.

Over time, Midnight’s behaviour became increasingly erratic and sometimes withdrawn. Living alone and hustling on the streets (he had run away from home aged 13), Gottfried became his go-to support. She wrote that Midnight’s “cycle was to become ill, get hospitalised or imprisoned, take medication and see counsellors, and then become a member of a program with therapy.” Midnight was eventually, and belatedly, diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The bond and tenderness between artist and subject underpins the Midnight series, but is accompanied by an indirect critique of the health and social care system. “I went with him to the Social Security office and to apply for welfare. It could take a whole day just to be seen by someone,” Gottfried recalled in her Midnight exhibition statement. “Helping Midnight was an exhausting commitment. At times he was doing very well and could hold down a job, but eventually his illness would kick in and he’d be off and running.”

“She took her first photographs at Woodstock in 1969, admitting later that she had ‘no clue what I was doing’”

The making of the Midnight series ended in 2002, though Cooney says they remained in contact until her death. “I believe that Arlene kept in touch with Midnight until she passed away,” he says. “Midnight came to see the show just before it opened. He is very fond of Arlene and deeply understands what she was doing while photographing him.”

From the early 1990s, Gottfried joined the gospel choir that became the subject of her first book, Eternal Light (1999). A noted soloist for her powerful voice, she went by the name of the ‘singing photographer’. She sang with the same raw intensity and directness that can be discerned in her photography. It came from the soul.

“Described as shy or modest by those who knew her, Gottfried always demonstrated a curiosity and willingness to approach strangers”

Towards the end of her life she created Mommie: Three Generations of Women,

a series chronicling the women in her family over the course of 40 years. It featured her sister, mother and grandmother (‘Bubbie’) eating, getting dressed, crying, kissing one another goodbye, and eventually dying.

The most intimate and exposing photographs of the series capture her grandmother and mother’s decline. They show periods of time spent in clinical hospital rooms and nursing homes as they become frailer. “That’s how I knew how to cope with it, by taking pictures. . .that’s how I dealt with the pain,” she said in Gilbert, a documentary about her actor and comedian brother.

Not long after Mommie was published, Arlene’s own health deteriorated and she was diagnosed with cancer. She died on 26 August 2017. Gottfried enjoyed success during her lifetime, though she never became a household name. “It’s something we’re trying to correct now,” explains Cooney.

“Arlene did not enjoy being the focus of attention, but I know she enjoyed the accolades that her work received. I’m quite sure that she felt, as do many people, that she was overlooked during her lifetime.”

Lydia Figes is a culture writer and editor specialising in the visual arts

Arlene Gottfried Exhibitions

Midnight, Daniel Cooney Fine Art, New York, until 5 March

Clandestine: The Human Body in Focus, Cobra Museum of Modern Art, Amstelveen, Netherlands, until 27 March

VISIT WEBSITE