I write about art and I look at it a lot. But I don’t typically go to fairs. The throngs of people and the pushiness and the, I don’t know, the feeling of vanity and hustle. The settings have never appeared conducive to sensible curation or critical reflection. It’s just not a place for me—misanthrope and semi-agoraphobe. These are all already endemic in the arts, I know, but it’s just too much of too much.

This year, however, I tried again to dive in, visiting the Independent and Armory fairs in quick succession on opening day and first public day respectively, hoping to catch the febrile mania they seem to inspire in so many, or at least the warm appreciation they command from so many more.

My first stop was Independent. After getting my pass from check-in clerks scrolling through social media, I headed upstairs and took in the scene, slowly. Here was Karma and some funny handmade porcelain dolls by Andrés Eidelstein. People went ape for them. “They kept swapping out the action figures,” a friend later remarked, “Trump for Snoopy, then Garfield.” There were two full tables of them—Miss Piggy, Princess Leia, Chaplin, Matisse’s dancers, dozens more—mashed, pseudo-naive, and paired jarringly with reductive paintings by Ted Stamm.

Earlier in the day, I’d read art advisor and market watcher Josh Baer remark, of the Armory show, “I thought artists were going to be more reactive to the new political environment in the States—but if they were I certainly missed most of it.” Such political concern was visible, in places, at Independent. White Columns, where Baer was once the director, exhibited their 2006 print edition, with Rirkrit Tiravanija (reading “USA: FEAR EATS THE SOUL”), along with another print by Richard Prince recreating part of a news item on American nudists, which, like Eidelstein’s dolls, can be read as both political and deflating rhetorical invective.

One floor down I ran into a few friends. Standing next to Patrick Van Caeckenbergh’s diorama-like display of glass bell jars on mirrored industrial shelves, at Lehmann Maupin, one remarked on the handsomeness of the space, from which a flood of sunlight was then receding. Another agreed. “The high overhead lamps are theatre lights,” the first pointed out. “Are we on a stage?” As if on cue, a dramatic gong and set of single-stringed electric guitars by David Shrigley began clanging over at Anton Kern’s booth. Anyone can play them.

I was surprised, despite their impressed judgment, at moments of disarray. I pointed to what was one of my favourite images, a palimpsest of Preview frenzy: a set of handsome preparatory drawings of black squares, along with two black squares painted on SPROVIERI’s wall, by Art & Language. Below them, a gallerist had plugged in their iPad to recharge, connected to an inky electrical cable via a black box and white European adapter, with the tablet leaning up against the wall like a small, black square of its own, an incidental complement.

What could seem at first glance to be outsider art at Andrew Edlin Gallery was, in fact, the work of Beverly Buchanan—rough-hewn sculptures and drawings, based on ad hoc, hand-built shacks made by the impoverished people who lived in them in the southern United States. Buchanan recently had a modest retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum, showing work like this and her totemic cast-concrete sculptures. And, at Delmes & Zander, the Disko Girls series, actual outsider stuff: drawings of buxom, disrobed women, in the mode of Egon Schiele, by an anonymous artist, made in the 1980s.

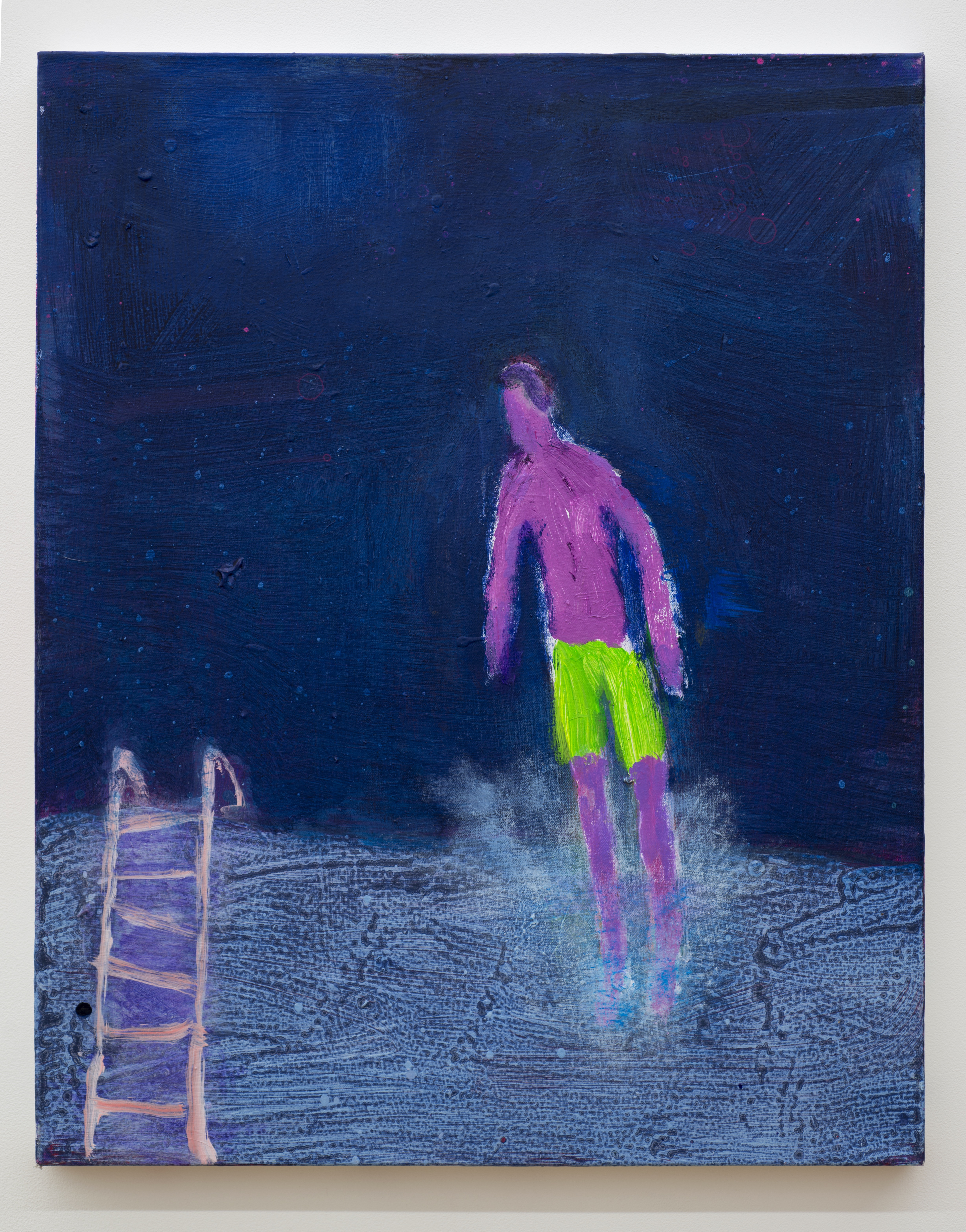

We passed by a sculpture by Robert Janitz, a nubby plant made of drooping pink-painted steel leaves and white plastic base. Janitz’d mentioned to me once that he thought of those pieces as jests on designer Martin Margiela. This one sat across from and chromatically echoed, a Katherine Bradford painting, at CANADA’s booth.

Portland’s Adams and Ollman and New York’s JTT have a booth together and it works. I liked Charles Burchfield’s drawings matched with those by Conny Purtill: Burchfield’s nodding, naturalistic sunflowers and Purtill’s hazy, joint-smoking smiley face and soft line drawings. Juxtaposed with sewing-pattern-like gouaches of Ellen Lesperance and tiled, geometric sculptures by Jonathan Berger, they form a gorgeous tableau, like inhabiting Ellsworth Kelly’s oeuvre. Nearby, a woman on her phone in the Francesca Pia booth explained the complexity of filing her taxes while looking at bongs and a giant Muppet sculpture by Stefan Tcherepnin.

At Invisible Exports was a half-eaten cookie next to a half-finished bottle of Bulleit Rye next to a suite of mixed media pieces by Scott Treleaven. The Treleavens look like they’re frosted.

I took off for the Armory, leaving two friends to continue spectating and another to Instagram the fair for an art advisory. New York’s had a very warm winter, but on Thursday morning, cold blew in and it had become really chilly. Even more so on the way to the Armory. The sun had gone down and the wind coming off the Hudson was strong. Across from Piers 92 and 94, where the fair is held, in front of the Larry Flynt’s Hustler strip club, with its bizarre Greek columns high up on the façade, on a telephone pole, a pleading, taped-up ad aggressively asked whether contemporary art still exists. It seemed crazy.

Inside, the Armory staff were glued to their phones. That Instagram and fairs are a match made in heaven, with a stream of loosely associated images rolling past, seemed more and more certain.

Just past the entrance, at the Artsy booth, people were playing with virtual reality headsets. There’s also an Artsy broadsheet printed for the fair (one cover story “The Rent’s Too Damn High”) and there are free copies of the Financial Times around. Paul Kasmin, by the way, at their 10th street location, has actually the best art use of VR that I’ve yet seen, in a piece by Michael Joo, whose work is also at Carolina Nitsch Project Rooms’s Armory booth—a silvery, dripping monochrome painting.

The Armory felt far less intimate than Independent. It’s huge, like a stadium, and looks more active and controlled, somehow, simultaneously. I felt sorry for the exhibitors who occupy hallways that lead to outside doors, with cigarette smoke and freezing air seeping or blasting in. Artsy reports that “The fair’s 23rd edition sees significant changes to its floorplan, thanks to the new leadership of director Benjamin Genocchio.” People drifted and skated around, eyes unfixed, many carrying free tote bags given out by the fine art services company UOVO.

Two Palms’s booth was stuffed with text paintings by Mel Bochner, which could be old hat, but are also kind of perfect in the din of all these people talking. A group of students nearby lamented that the only words they could find for what they’re seeing is that they “like this aesthetic.” Another guy walking by in a tracksuit beamed at how “art is so particular. To each really his own, you know?” It’s a spectacle, really, more than the close quarters of Independent. In the “Town Square,” a centrally placed Yayoi Kusama installation, a field of Astroturf with big psychedelic red and white fungal forms, presented by Victoria Miro, is labelled very strictly that people are not to touch. But benches are set up around it and there several people standing on them made big arcs with their phones, trying to capture the whole thing, under high, cold lighting.

Per Baer’s earlier remark, at Kaufmann Repetto, a big sign by Andrea Bowers flashes “RE/SISTERS,” an image which looks to be very popular on Instagram.

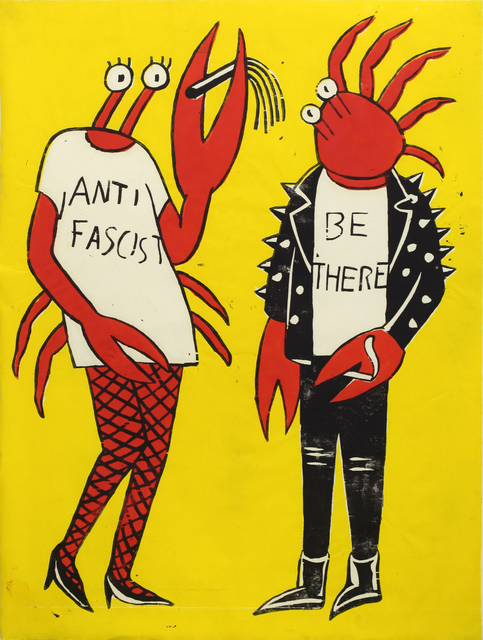

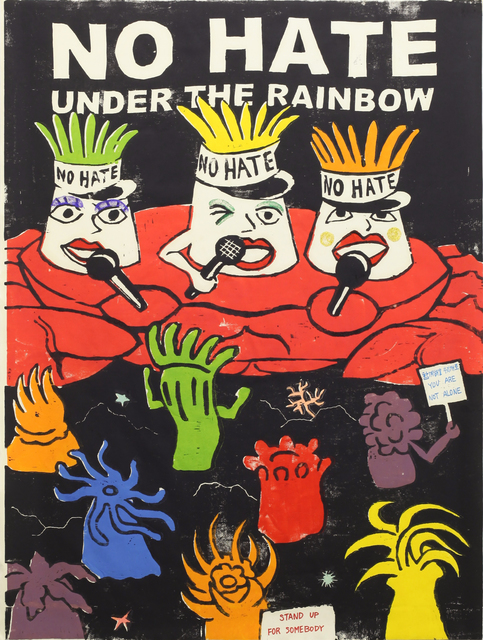

The hippie-ish prints of Nobuaki Takekawa at OTA Fine Arts seem cute and kind of bonkers. There’s little bohemian sea creatures smoking and wearing Antifa slogans on t-shirts and leather jackets, and they go to concerts. There’s also a campy sci-fi set with a rocket blasting off and models with bubble-dome space suits, which are less endearing, but just as bonkers. The whole thing’s staged right across from Jeffrey Deitch’s nutty homage to Florine Stettheimer and recreation of the 1995 Gramercy Park International, which preceded the Armory show. Deitch was holding court before a crowd of people, whom he was lecturing on the shows. This rendition, curated by Ricky Clifton, feels as though it could have been even more bananas, with excess colour, excess form, excess texture. But fairs can seem restrictive in the ability to make curatorial choices that go far beyond showcasing work.

That structure was more relaxed in the Presents alley of the fair, where booths present one- and two-person shows with a little more vibrancy. El Apartamento, from Havana, has a handsome curation of work by Diana Fonseca. Made from objects rendered unusable by their aestheticization (a book filled with rice, scissors whose bows have been covered with mounted stones), they’re reminiscent of Cuba’s fame for the opposite: repurposing used goods into useful tools.

By then things were closing up. I skimmed Lyles & King’s booth, Peter Blum, and Marlborough as I headed for the door. Someone from Axel Vervoordt caught me to describe the workings of a performance by Sadaharu Horio that was ending when I arrived. The former Gutai member sits in a cardboard box and makes paintings for a dollar. Horio went walking by and he, like everyone else, looked wiped out. There were bins of paint and stuff everywhere and the security guards were hustling people out into the cold.

I’m glad I went.