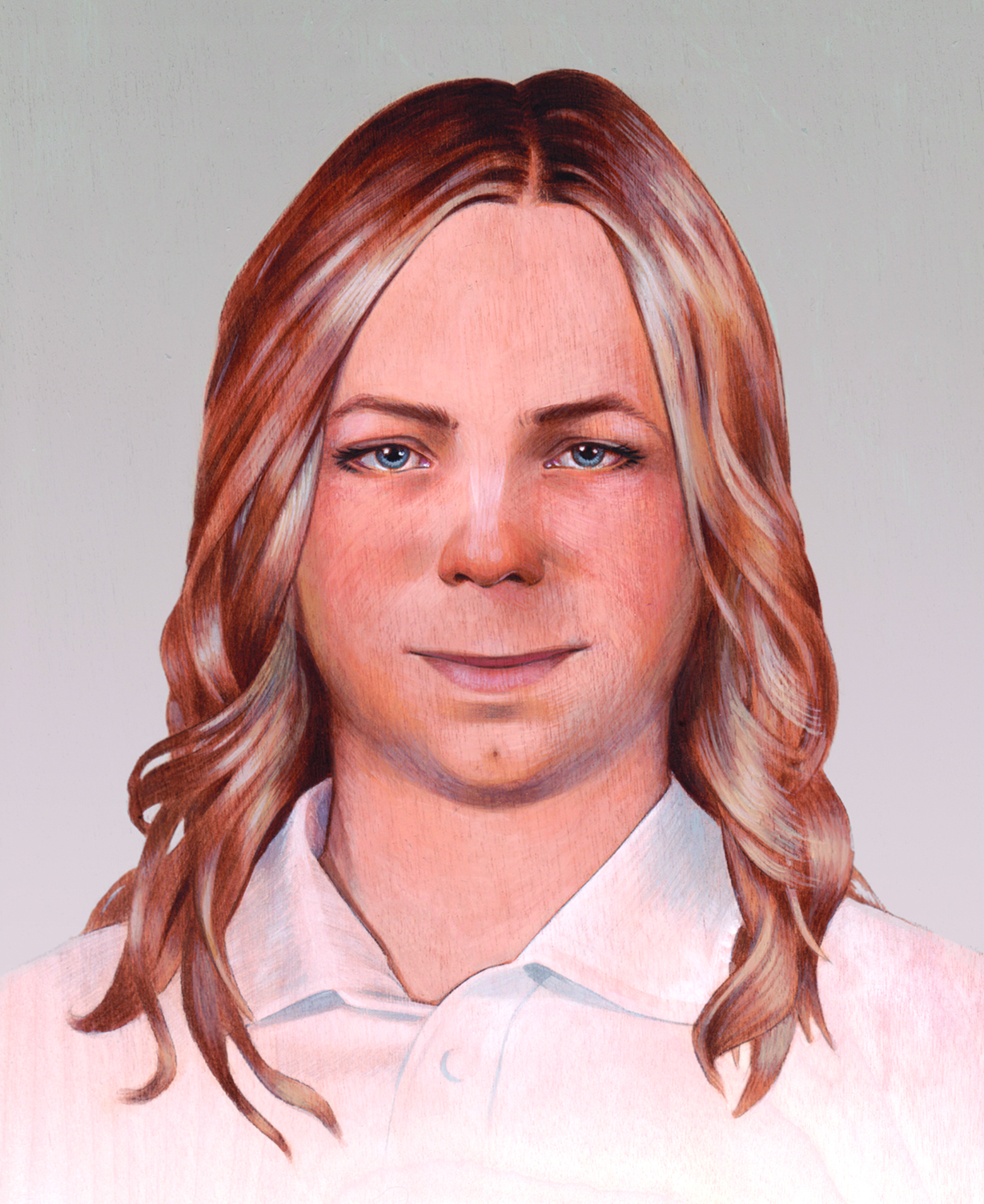

On the eve of Chelsea Manning’s release in March 2020, I returned to an essay I had written about a portrait that her support network had commissioned in 2014 while she was in solitary confinement. The artist, Alicia Neal, wanted to offer news outlets an alternate image to Manning’s military portrait while in solitary confinement at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas.

Manning announced her transgender status and desire to be treated as a woman in 2013, and I have always interpreted Neal’s portrait as an act of aesthetic resistance, a necessary step in honouring Manning’s gender in the absence of an integral public representation. Yet representations related to, or created by, the justice system are not always generated in response to misrepresentation or invisibility; they are also indicative of a deeply entrenched racial and gendered bias.

“Courtroom sketches appear almost fictional in style, eerily dislocated from their purpose of a supposedly neutral attempt at visual testimony”

Representations are changing in criminal justice, but it’s difficult to say if for better or worse. Courtroom sketches, those strange, rapidly drawn scenes of trials utilised by news outlets, have represented everyone from Amy Winehouse to Charles Manson as they faced criminal charges. Depending on your artistic eye, the scenes are a vignette of caricatures materialising as a visual testimony. To me, they appear almost fictional in style, eerily dislocated from their purpose of a supposedly neutral attempt at visual testimony.

They are now poised to disappear from public view. In 2020 new legislation, which would legalise filming inside Crown Courts in the UK of ‘high profile cases’, was approved, rendering the necessity for sketch artists void. These images have always raised an ethical quandary. Courtroom sketches are only required for criminal cases that the press can capitalise on: if you’re rich, famous or morally corrupt, they want a glimpse of the action. After spending time in the Old Bailey in 2017 while working on my book Ethical Portraits, I felt that the neutrality required of artists to correctly create this mode of visual testimony was emphatically impossible to achieve in the courtroom.

I hope that the legislators of the new act remember the 1995 OJ Simpson Trial in the United States. Prior to the case live coverage was deemed acceptable, and the media were hungry for newsworthy developments. When the trial began on 24 January 1995, it was televised for 134 days by network outlets, and is renowned as one of the most publicised trials in history. Not only was it soap opera-esque in tone, style and orchestration, ninety-million viewers tuned in to watch it, with TV stations interrupting the 1994 NBA Finals to air it. With the passing of the new Crown Court (Recording and Broadcasting) Order 2020, it surely won’t be long until we see another narcissistic murderer hogging the representational field once again.

In Ethical Portraits, I also investigated the systemic ethical failures that have emerged when memorialising those subject to the perpetual violence of the white supremacist police state. In the case of Eric Garner, the horrendous footage circulated of his death in 2014 was the first place where he gained representation. The viral online afterlife of this footage saw it become stuck in a repetitive loop, with no relief from the conditions of his death, and no alternative story to know this man by. This repetition and recital only reinforces the ethical question of how and where fraught ethics of accountability and recognition occurs, particularly if we only remember the person murdered simply for the documentation of their death.

“In the case of Eric Garner, the horrendous footage circulated of his death in 2014 was the first place where he gained representation”

In 2020 the horror of George Floyd’s murder spread like wildfire around the world. It sparked global protests organised by the Black Lives Matter movement, but memorialising could also be seen in the creation of public murals. These murals of George Floyd can be seen in places from Texas and Manchester to Syria and Palestine.

The first to appear was on the corner of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue South in Minneapolis, undertaken by artists Xena Goldman, Cadex Herrera and Greta McLain. Within 12 hours of its conception, the artists had finished the image. The symbology of the mural’s meaning is twofold, the reckoning with police violence both horrifying and a necessary warning of that brutality. But I feel that it also pays a profound homage to Floyd. It is up for debate as to whether these images incite a form of mourning or are a pure indication of ‘honouring’. The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act of 2021 marked a political turn of recognition, where Floyd’s name (now bound to a civil rights reform bill) signifies racial profiling and police misconduct within a legal sphere.

When I see these murals, an inherent question of mourning comes to the fore, the intricacies of how we collectively respond to the feeling of detention, imprisonment and violence. We must disentangle the intricate web of agency, over-representation and voyeurism if we are to understand who gets represented and why. This context demands a new interrogation not just of the way in which we look , but also the ethical and political frameworks in which these images are produced.. It is about acknowledging the new forms of visual memorialisation which can emerge in the wake of the justice system’s failures.