After the unpredictable political events of 2016, it has been noted that we’re living in a bubble of sorts, blissfully unaware of the existence of views besides our own. Could art, the big communicator, help us to see the other?

As we near the end of 2016 it seems fair to say that it’s been a surprise. In the last month Donald Trump become the President-elect in the U.S., the Netherlands moved towards banning burqas and France’s Marine Le Pen became a favourite to win in their upcoming elections. Currently, Britain is trying to settle into a true Brexit, and Austria is readying for its political overhaul to the right. Across the ocean, the new leader of the Philippines, Rodrigo Duterte, is readying to dump America and start courting China. Even Angela Merkel, the German darling, might not hold onto her big power. So, where is the art world in all of this?

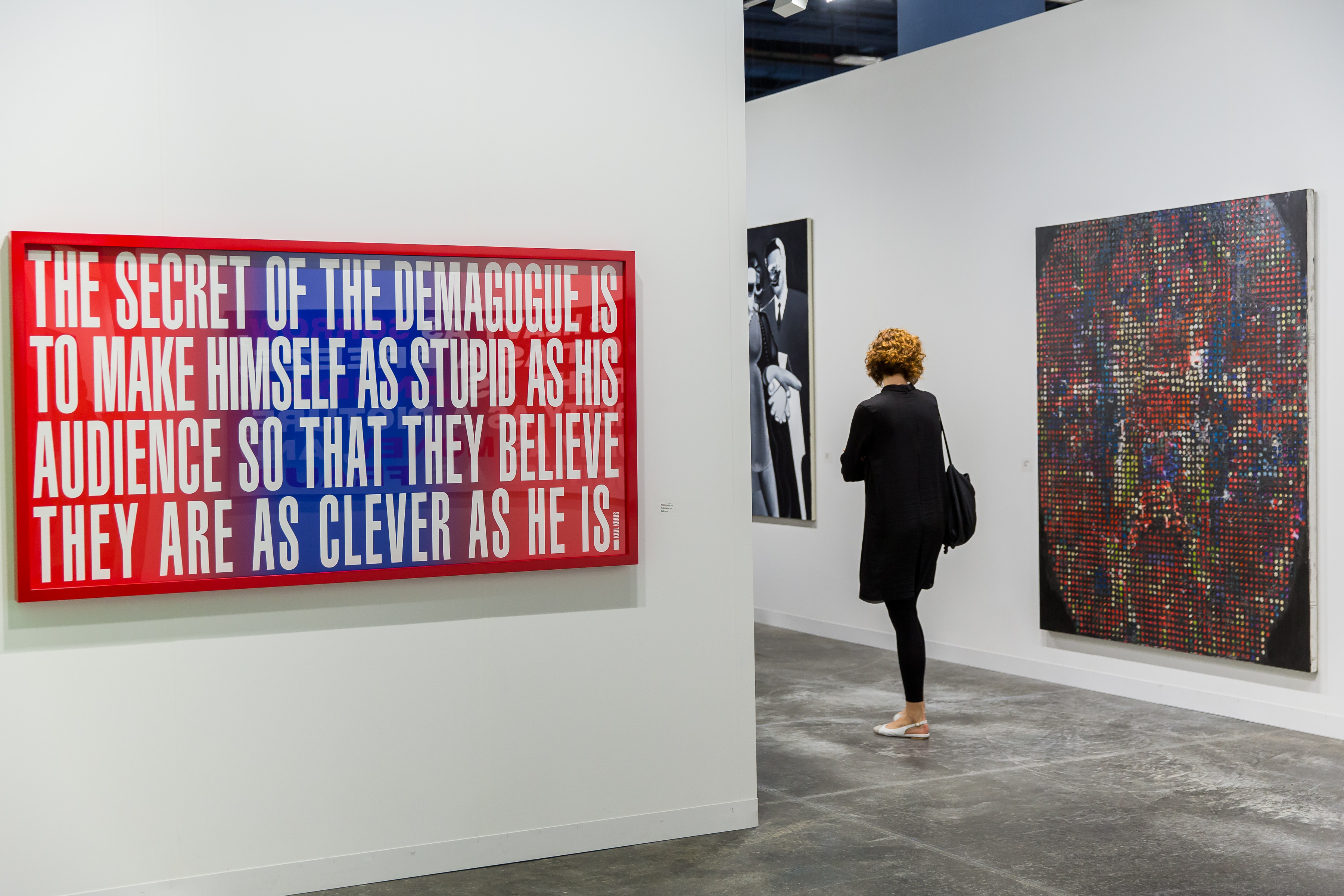

Some might say the art world (more than fashion, design, architecture, food etc.) is placed to be a barometer of some kind, emulating the world’s sustenance, and its residue. I’m walking around the blanched passages of Art Basel Miami Beach looking to gauge the temperature — but I’m not quite seeing the whole picture am I?

It’s hard to read a paper, magazine or any website in the last few weeks without seeing a piece that discusses our current “echo chamber” existence — some of these articles are even popping up on Facebook, the biggest echo chamber of all. The “we” is unclear (are “they” seeing these articles too?), the result isn’t. The polls for the U.S. election and Brexit had it wrong, and the masses of people who represent the winning side must have come from somewhere; whether I, “we”, saw them or not. We’re talking millions of people here.

Can the art world show me who some of these people are? Maybe we can even be friends?

“Art always responds in unique ways to the politics, culture and media of its own time,” Daniel H. Sallick, Board Chair at Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, tells me. “What’s great is that art is prismatic – it crystallizes an idea and lets us see it from multiple angles. Now artists and the larger art community are in a great position to help create the change in our politics, media and world that we want to see.”

I did find a small number of galleries pointing out socio-political matters here at Basel this year. After all, the fair’s director Noah Horowitz said, “We are in a moment now of great political transformation and social change in America, and a number of works that have been created respond to that.”

Sam Durant, the American artist, created two works addressing race relations in the country — a large backlit sign shows the words “End White Supremacy”, another “Landscape art is good only when it shows the oppressor hanging from a tree by his motherfucking neck” behind a brick wall. Of course, these references address Trump’s proposed wall between Mexico and America and a sliver of his support base.

The Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija is exhibiting a three-panelled tryptic featuring newspaper headlines (“Trump Triumphs”) with overlaid bold red letters “The tyranny of common sense has reached its final stage”. Pedro Reyes, from Mexico, has created a wooden sculpture that resembles the Statue of Liberty with the title Lady Liberty (as a Trojan Horse). Statements are everywhere though they tend to sum up the prevailing mood within this particular bubble.

Where is the big reveal of populism and what that looks like? Where is the right wing artist showing us their world (if they were here, would they sell, be egged, be heckled)? Nobody addressed the shift from left to right we are witnessing in such a grand way, but some peripheral, and still very important, issues received treatment as pointed out. Is art about agreement or food for thought? Should we be looking for insights and education over validation, whether we like the views we’re shown or not?

Of course, we expect the sensibility of most visual artists to be predominantly left-leaning, though there are cases of those swinging the other way. In 2013 The Guardian selected the top right wing artists, including some surprises — Gilbert and George were mentioned for their work that celebrated skinheads (and indeed quoted with the following: “We’d rather side with the bankers than some vegan protester twit on benefits.”), James Gillray was also given a nod for his reception of funds from the British government to create art that mocked the French Revolution.

In the end though, the celebrities walking around often attract more attention than the art. How could we possibly see outside of this bubble? It’s gilded for the most part, and can often appear to be no more than a one-way mirror.

Mary Boone Gallery © Art Basel