The future and the past are common themes at Miami’s Art Basel, as we look back and forth for information, warning and insight. There are also many works that speak to the marginalised; from women to suburban neighbourhoods in Philadelphia.

I approach Art Basel Miami Beach — held at the convention centre, where caffeinated members of the press wearing black and navy stand outside in small groups, smoking — expecting to escape some of the recent debates that have raged in the U.S. I inhale a little cloud of that smoke and walk in. The future immediately asserts itself.

The quote by Varvara Stepanova, in the Claude Picasso-designed booth that Malevich would have been proud of, sets the tone. With its red and white constructivist palette, the booth cannot be missed; it is the first thing that confronts a visitor upon entering the fair. I decide to look for clues of what brought us into this new political climate, and what will happen next. Anxiety over the future is undeniable, just like it was in 1919 when Stepanova drafted the original statement on her poster during the time of the Civil War in post-revolutionary Russia.

After a few booths filled with oversized shiny baubles intended for what seems like oversized shiny toddlers, the energy of rebellion resumes in the works by Marcelo Brodsky, an Argentinian photographer, human rights activist and economics graduate from the University of Barcelona. His work is focused on abuses of human rights and political activism in recent history. Brodsky appropriates archival news images of protests, interspersing them with his own handwritten messages. With decades of experience running a large-scale news photo agency in Latin America, Brodsky has a deep understanding of image sequencing and the power of interpretive captions. He creates striking narratives, drawing you in with emotional and sensory experiences. In the age of anxiety, the heart longs for concrete answers, and in providing those, written word has unrivalled power.

Further on, in the booth of Kamel Mennour, Paris-based Mohamed Bourouissa explores the condition of a marginalized community in his new sculptural works from 2016. The project stems from Bourouissa’s earlier photographic series about a suburban neighbourhood in Philadelphia whose inhabitants rely on horses for transportation. Bourouissa’s black and white images are printed on car body parts, which are then bent and layered into dynamic compositions. The large-scale works monumentalize the subject and come through as metaphorical and prophetic. With so much visual stimuli swirling around me, my brain begins to scan for patterns.

I notice a group of small brightly coloured canvases on the wall of P.P.O.W. booth. In her text-based works Betty Tompkins, a British painter whose work has recently gained long-deserved historical recognition, explores the language routinely associated with women. In 2002 and 2013 Tompkins sent out an email to friends and acquaintances soliciting for words that are most often used to describe females. She received over 3,500 replies in seven languages, which listed both positive and negative words. The four most common ones were cunt, bitch, slut and mother. The artist then transcribed the words onto small canvases, which now comprise her WOMEN Words series of 1,000 paintings.

I drift from Tompkins to Jonathan Horowitz, Does she have a good body? No. Does she have a fat ass? Absolutely, the title reminding me of an incident a few years ago when a man grabbed me by the ass in a subway. It was in the middle of the day, the subway packed with people. Of course, this was not the first time I was harassed, but the first time that I, after walking away and brushing it off as usual (“he’s probably drunk”) turned around, heart pounding with adrenaline, and ran charging back full speed, knocking him down. A crowd gathered, someone applauded, nobody helped. I jumped into a car fearing he’d get up and punch me back. I felt triumphant nonetheless.

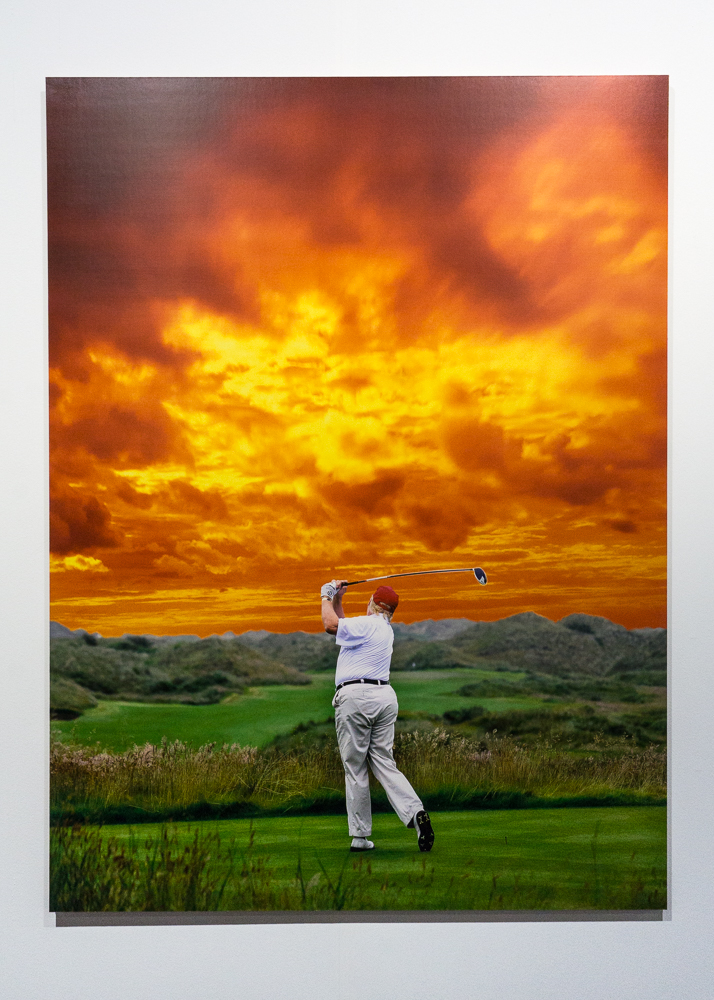

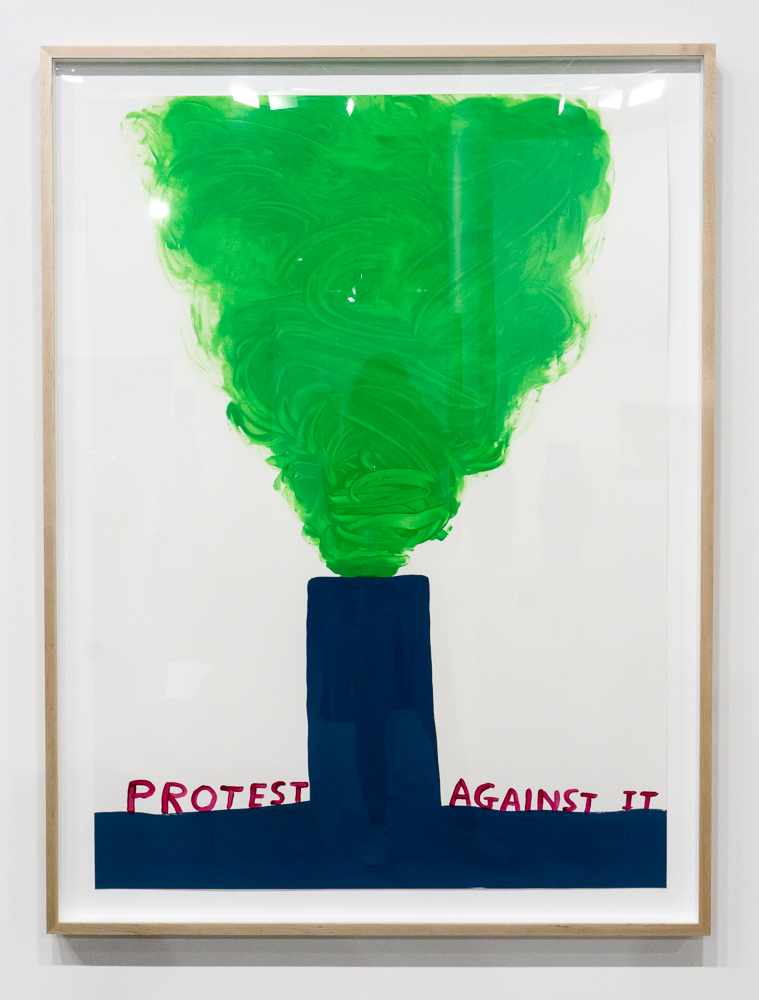

As I hurry past the last few dozen booths, taking long strides, trying not to get distracted by numerous chromes, mirrors, neon, and colour gradients, I think about the future. I notice a few more important clues, like David Shrigley’s Protest Against It at Anton Kern’s booth, and an entire wall of Andrea Bowers’s posters on the outside wall of Kaufmann Repetto. At this point in my 4-hour stroll, the future looks alarmingly different for the target audience of the giant shiny multi-million dollar creations, and those who could not spare $50 for a day ticket. Immersed in my thoughts, I get tapped on the shoulder; worried I accidentally brushed against an artwork, I turn around to a smiling face. A woman, an avid art collector, recognized me from somewhere online and wanted to say hi. She has been coming to the fair for years with her husband, but prefers to do the actual exploring on her own; it helps her stay focused. She says they only collect the work by minorities, particularly emerging women artists for whom the purchase directly affects their livelihood. After a warm goodbye, I leave thinking that there should be a separate map for what’s important, even a postcard-size would do. It could be a start.

“It is the business of the future to be dangerous.”

A. N. Whitehead

‘Art Basel Miami Beach’ runs until 3 December artbasel.com/miami-beach