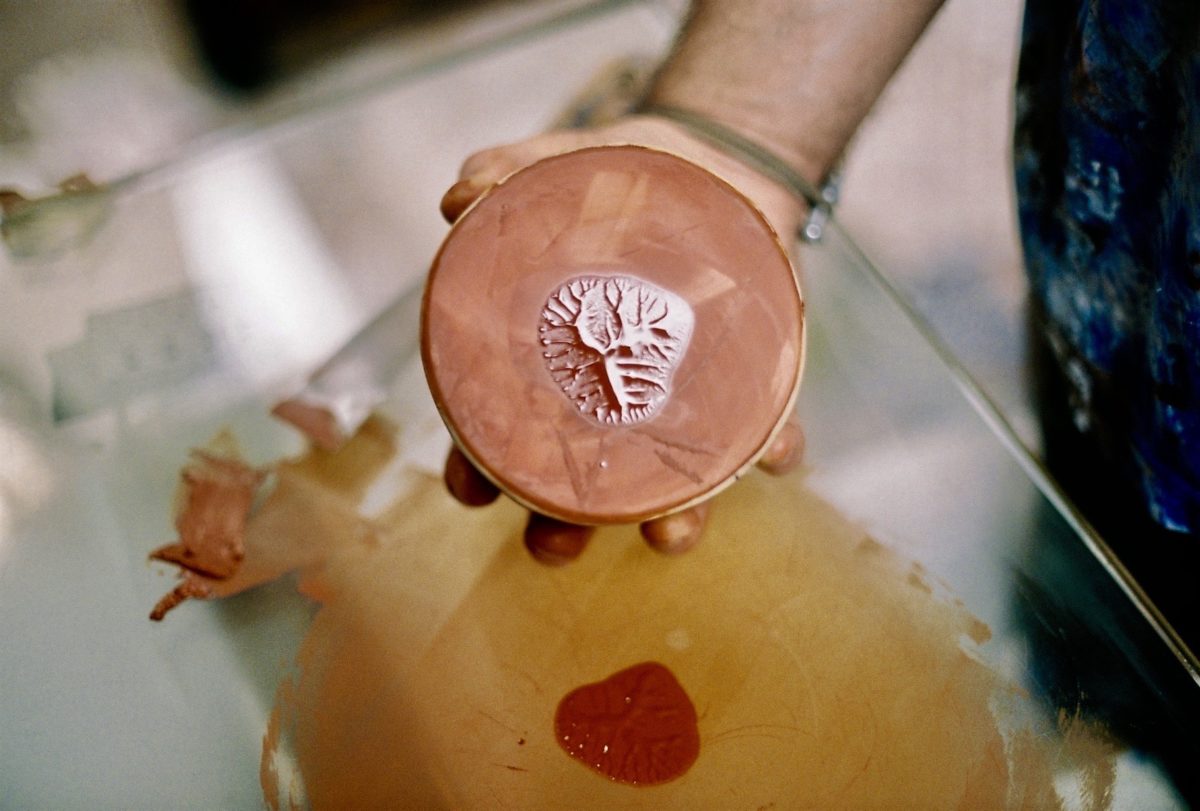

Thierry Moutard Martin studio photographed by Benny Matthews

There’s something wonderfully romantic about art forgery

—the idea of someone perhaps in a rickety loft apartment in Paris, knocking off world-class artists and fooling the wealthy into parting with their wads of cash. It’s the stuff of old movies, that makes us think of a more “simple” time. Do forgers still exist? And how are they able to operate in a more technologically savvy age?

Art is becoming a more stable asset category. Investors who spend $2,000,000 on an Old Master work and stash it in a free port are likely to receive a stable return on their investment. Yet the most effective means of emptying the asset of any monetary value is by proving the work to be fake; a million dollar Constable is reduced to a couple of hundred quid from one minute to the next.

It is for this reason that technologies detecting forgeries are being developed so quickly. Isotopic analysis and carbon dating cost a lot of money, but it’s a fraction of the potential money lost should a work be falsified following acquisition. It has been stated in numerous sources that an approximate 20% of artworks in museums are fakes—and there was news last year of a French museum discovering that half of all its works were of questionable background. But how easy it is to pass a forgery test nowadays on a newly created work?

- Thierry Moutard Martin studio photographed by Benny Matthews

I recently visited artist Thierry Moutard Martin in his studio in Versailles, west of Paris—he is also a paint-maker and restorer, who works closely with a number of auction houses in Paris, and he teaches on forgery in the art market. His shelves are stacked high with jars containing flakes of lead white and takeaway containers with azure rocks and ochre stones used to grind paint from scratch using the same techniques as the Old Masters. What I presume to be a highly convincing reproduction of a Dutch Old Master stands in the corner. “I see what you’re getting at,” says Thierry, “this studio is well equipped to produce forgeries; it would be the perfect place to do it.” I’ve just asked him if he’s been approached by any nefarious characters offering him an entry to the dark underbelly of the world of fakes. But Moutard Martin hasn’t chosen to be straight edge out of any moral obligation to legality, working with institutions and art dealers on research projects and authentication processes, but rather because, he says, “the era of the Great Forgers is over”.

“Forgery techniques that were once watertight have been outstripped by advances in technology”

- Thierry Moutard Martin studio photographed by Benny Matthews

Said era is over because of the above-mentioned, investment-driven impulse to develop comprehensive technology that aims to eradicate any potential fake. Forgery techniques that were once watertight have been outstripped by advances in technology, and paintings previously authenticated are at risk of having such status revoked should they be subjected to newly developed techniques.

One notable example is the use of titanium white. Any forger worth their name, will know that titanium white pigments were first made commercially available in 1921 and therefore to use it in one’s painting is to commit forgery suicide

. So in order to avoid using titanium white forgers must develop the pigment themselves, a process involving the fermentation of sheets of lead in vinegar and carbon dioxide. (In Thierry Moutard Martin’s studio this takes place in a large plastic box with yeast and sugar.) This has been, since the prolific career of Vermeer forger Han van Meegeren, a fool-proof technique for avoiding detection.

- Thierry Moutard Martin studio photographed by Benny Matthews

As a small anecdotal aside, it is worth noting there have been a number of forgers caught out, not through a use of titanium white in its pure form, but through the accidental presence of the pigment in their paintings. What these forgers did not realize, was that the industrial cobalt blue pigments they were buying up were frequently cut with titanium white and a much cheaper ultramarine blue pigment. However it is no longer sufficient to make your own flaked white paint. New isotopic testing can detect the age of the lead used to produce the paint, thus rendering the process completely transparent.

There is rumour of one particular forger still coming up with improbable means of staying one step ahead of these rapidly evolving technologies though. His work is documented in Jules Francois Ferrillon’s Faussaire (2015), a thinly veiled account of the real life stories from the world of art trafficking. This forger, knowing that using lead produced today to make pigments would make for an anachronistic reproduction, uses a metal detector to source lead rods used in ancient constructions in Italy. Somehow extracting the lead and using it as the base for white paint allows for paintings that pass even the isotopic test.

“The invention and the theatre involved in the pursuit of duplicity seems to be a wholly adequate illustration of creativity”

A lot of moralizing takes place in order to justify our outrage at the crumbling financial value of a painting discovered to be fake. One argument commonly made, that attempts to use aesthetic judgment to justify monetary value, is that a reproduction lacks creative originality, a notion which is largely accepted to be integral to our notion of art. I’m not sure I buy it though. The invention and the theatre involved in the pursuit of duplicity seems to be a wholly adequate illustration of creativity, admittedly different to the creation of original form. But maybe I’m being facetious.

I also spoke to Guy Ribes, infamous in France for his colourful autobiography and his prolific career as a forger, a few months after his release from prison. “A copy is not a work of art,” he had told his court hearing. “But these are not simple copies.” Ribes would produce work “in the style of” any given modern artist, that his middleman would later “find” in the loft of a neighbour or some other imaginative spot. And so while Ribes’s work might lack stylistic originality (in terms of brushstroke, colour palettes etc) it certainly can’t be reduced to a catalogue of reproductions, there is creative original content in every one of his paintings. What’s more, he doesn’t consider himself to be a forger, with reproductions and style-of paintings being one of the most widespread modes of production during the Renaissance, rather “It’s our consumerist society that has spawned this crime,” he says.

Neither Ribes nor Moutard Martin, who come from either side of the legal spectrum of the same practice, feel the need to ardently denounce forgery in moral terms. One gets the impression they both feel a sort of nostalgia for the rapidly declining possibility for reproduction. In both cases it is a passionate practice, it is certainly not particularly lucrative for those actually creating the work. Both recognize it is an act of theft, the forger and their network retain profits made, while buyers, once left with a falsified painting, loose their invested money. However it’s not a crime attached to plagaristic appropriation of authorship, it is an undermining of “expert” committees, and an exploitation of a speculative economy of commodity investment.

Thierry Moutard Martin might be sounding the death knell for the fraudulent reproduction of Old Master paintings due to two factors: the difficult of historic reproducibility, and secondly, their preferential status as commodity objects of investment. There is however conceivably still space for another Guy Ribes, working alongside their respective near contemporaries, and thus avoiding any anachronistic inconsistencies. However all the time the art market continues to operate as an asset category for investors, the technology for falsification will continue to be developed at break-neck speed, cracking down on the strange and seedy world of art traffic.