Over the weekend, visual and performance artists from around the world made a New York City street their runway in a provocative and joyful intervention of public space.

If you were walking down Manhattan’s 14th street towards the Hudson River last weekend, you might have passed by a man in a silver feathered, knight-in-shining-armour-suit. Or maybe you would have been distracted by a woman in a giant, white, geometric cardboard dress gliding by. If you kept walking, you could have run into a group of Fluxus artists parading around in black blow-up suits or dangling a fedora from a fishing rod.

Nearby, if you took your eyes off your phone at the right moment, there’s the possibility you would have seen the frenetic serendipity unique to New York City. A procession of colourful silk flags marched by a duo of black-clad performers with patterned tie hats who were swinging from scaffolding behind a woman crouched on the sidewalk, weaving a loom; a few curious pedestrians paused to observe the scene, which was punctuated by a gaggle of photographers crossing the street after a nondescript man and woman, the latter who, according to word on the street, was Isabel Díaz Ayuso, the President of the Community of Madrid.

If you made your way to Union Square, you would have happened upon the meeting ground for Garbagia and the concurrent Garbage Fest: a cohort of clowns and gowns aptly made of garbage engulfed in the pungent scent of burning rubber.

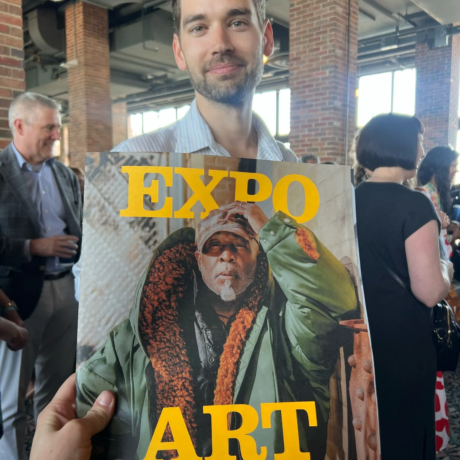

This is Art in Odd Places 2023, a weekend-long guerrilla art festival that has travelled the corners and awnings of 14th Street annually for 18 years. To the unassuming passerby, these happenings might seem unrelated, the occurrences of an average New York day or possibly a spillover from the costumed chaos of Times Square.

Despite its spontaneous approach, the grassroots festival was curated and staged by a small group of dedicated volunteers and organised by Ed Woodham, a visual and performance artist, curator, and SVA educator who was a MacDowell fellow in 2019. This year’s prompt, “Dress,” curated by Gretchen Vitamvas, transformed the city street into a runway. Last year’s theme posed the question: what is normal?

Prior to curating AiOP, Vitamvas had participated in the festival eight times, an experience she credits for helping transform her art practice. “Before I started working with AiOP, I was doing two-dimensional work,” she says. Her first piece for the festival was subway camouflage, a mix of orange, yellow and chrome.

“AiOP is a scrappy, DIY, guerrilla art festival, and there is always an element of surprise,” she adds, noting the different directions the word ‘dress’ was taken: gender identity, cultural expression, colonialism, fast fashion and waste, beauty standards, blending in, standing out, the list goes on.

“In terms of gender, trans rights are under attack right now, and clothing is a way of expressing one’s truth and identity,” Vitamvas emphasises, citing Molly Vaughan’s “Project 42,” which features custom garments that honour the lives of trans individuals who have been murdered.

Towards the end of the first day, Vitamvas watched a massive paper dress arrive on 14th Street, convening with Blanka Amezkua cloaked in a botanical dress and Chris Kaczmarek in a tiered neon orange hoop dress made in collaboration with Patricia Miranda. “Seeing all the dresses together with a big crowd around them was an incredible moment,” she laughs, likening the fanfare to a celebrity appearance.

Like many of the participants, Vitamvas was drawn to AiOP for the unconventional, art-outside-the-gallery approach. “When you take art out of the rarified spaces like museums and galleries and make it available for all, it becomes truly about the art rather than commerce,” she says. “It feels pure.”

Over the weekend, artists from Bangladesh to London to Chicago to Greensboro to Santa Fe clothed in wearable art proceeded up and down 14th Street rain or shine: Friday, they circled the east side, Saturday the middle, and Sunday, they went west towards the High Line.

Some performers took the theme and expanded on it — larger-than-life costumes with billowing materials— while others subverted it to curious and shocking ends. Kasie Campbell, the latter, carried white sculptural objects made of breast milk while wearing her late mother’s wig and a 1950s-style dress embellished with writing describing postpartum depression and lamenting the loss of her mother. The breast milk slowly melted, dripping onto the sidewalk as Campbell carried the objects up and down the city blocks. Vanessa Fairfax-Woods explored the stigmas of being “fat” with a costume inspired by her body: fabric printed with images of her own flesh contorted, cradled and exposed her figure.

A revolving cast of characters popped out from every corner. At one point, a man who introduced himself as the Sticker Dude presented me and my group with a box of stickers: there was Trump with a dragon as a nose and a still life of a Buddha’s hand citrus. As we rifled through the assortment, he told us about the origins of his eponymous craft, the postcard art movement of a bygone era. I picked up a sticker with a handmade drawing, which Sticked Dude shared was emblazoned with Grateful Dead lyrics that he proceeded to read to us with theatrical aplomb and unwavering but evenly distributed eye contact.

Later, as we were making our way to the subway, the aforementioned hat-on-a-hook lowered over one of our heads. We laughed and posed for photos. The merry trickster, Vivian Vassar, was also wearing a Bowler Hat. Vassar is a seasoned Fluxus artist of Day De Dada, a Staten Island performance art collective. “We are in the middle of a four-day Fluxus event,” she said, adding, “I do it for fun — I love performance, but I like it on a lighter note, not too serious.”

Underneath an elevated railway, movement artist and choreographer Darling Squire undulated her body to the rhythm of a poem read by Kristin Mariani as commuters climbed up the stairs to catch their trains. “We are collapsing the space between private and public,” says Mariani, a dressmaker, artist, writer, and professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “What we want is conversation. Attention without conversation isn’t the same,” she told me as I inquired about her and Squire’s matching constructivist-style dresses that came from her past installations.

There were spontaneous moments, side quests, and the recurring question, “Are they part of the festival or just an eccentric New Yorker?” I left with pockets full of business cards, stickers, and a poem by Kristin Mariani posturing as a clothing tag.

“It is very difficult to punctuate the sidewalk of New York,” laughed Mariani, “but I don’t mind that. Everyone has their own life and their own purpose, and you’re not that important. Life is important.” She also used the time on the city street to collect elements of text from the city facades to use in later writing.

Woodham refers to the majority of AiOP’s audience as “the uninterested” pedestrians, he tells me, who he views with reverence and empathy. “You don’t know what anyone is going through and experiencing in life; they may have four kids and be struggling to get to their second job,” he says. While everyone does not have the privilege of time and mental space to pay attention to art, Woodham offers a brief encounter on the street that might, at the very least, bring a moment of joy.

It is important to Woodham that AiOP and its practitioners mindfully offer their performances to the general public who might not have time for art that day. “You have to respect the space, let people walk through comfortably, and not easily block their way,” he says.

AiOP first took New York City streets in 2005, when Woodham moved from Atlanta, where he had founded the festival two years earlier. The festival started in the East Village before moving to its current location on 14th Street in 2008.

Why 14th Street?” It is where the grid begins,” explains Woodham. “It seemed like a perfect thoroughfare. It has a history of political activism with Union Square. It’s the longest spread from the East to the West. In the past, anything below 14th Street was cool, and anything above it was uncool.”

In AiOP’s early years, 14th Street boasted mostly mom-and-pop stores, mostly electronic shops and wig boutiques: “The perfect combination,” laughs Woodham. “I watched 14th Street change from boomboxes to walkmans to handheld computers,” he says. “The attention span of the general public changed from a macro experience to a micro experience with smartphones,” he adds. “Getting people’s attention is a bit more difficult now.”

Getting people to look — to stop and see details of the city and its inhabitants with new eyes — is at the heart of Woodham’s tender and provocative efforts. “It’s not just about experiencing art in odd places; it’s about interrupting the habituation of how we experience the public sphere in New York,” he says.

Today, walk into any public space, courtyard or city park, and you will likely observe New York’s ecosystem in full swing: people camping out due to necessity, others taking lunch breaks from retail jobs, smoke breaks in business suits, tourists resting on the shells of their suitcases, teenagers scrolling on their phones or skating over steps, people having heated phone calls, eating halal, watching the birds.

Woodham’s ethos is an emphatic reminder that “Public space is ours. It is where we gather to share laughter and curiosity, to have conversations about change in these challenging and volatile times.” He teaches his students at SVA untraditional ways of viewing that shake up the routine of looking beyond eye level: He often takes each class to the city streets, where he instructs them to lie on the sidewalk, close their eyes and listen before opening their eyes and looking up.

Outside of AiOP, Woodham’s sprawling conceptual practice underscores the value of public spaces and historic preservations through public art that often incorporates activism, performance, and sculpture and costume. He also runs a gallery salon, Showroom, out of his home in Murray Hill.

Woodham is currently working on a collaboration with Chicago-based artist Juan Hernández — who was incarcerated with a life sentence as a minor (now illegal) and is awaiting a resentencing. The “Reverse Order” exhibition will run from December 16 to February 4 and feature a series of commissioned portraits.

While he is already beginning to think of AiOP’s next programming, applications won’t open until the spring. In the meantime, between his various other projects, Woodham is taking moments to stop and look, a practice he promises would generate surprising and inspiring effects for his fellow New Yorkers.

“Slow down and look at as many levels around you as possible,” he advises. “Be conscious of the levels of New York: the ground, the mid-range, eye level, a little higher, and then look up.”

Words by Meka Boyle