This article was created in partnership with Perrotin

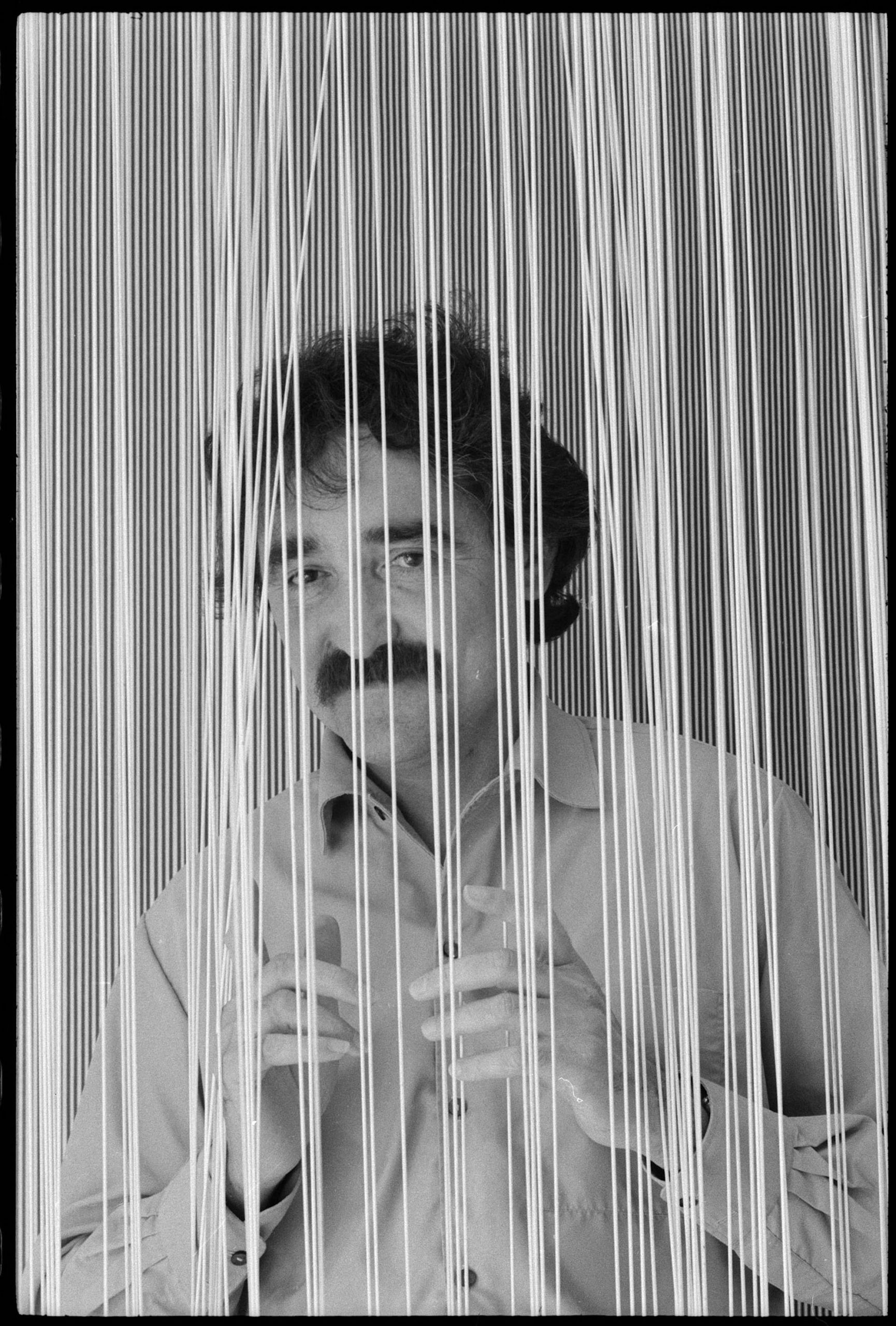

Early in October 1950, Venezuelan artist Jesús Rafael Soto stepped down from the Italian cargo ship Olimpia onto the quay at the port of Cannes. The 27 year old had left the city of La Guaira on 16 September in possession of a Venezuela state scholarship to study in France. He arrived in the south of France after a two-week crossing and immediately caught a train north.

As he later told the collector Claude-Louis Renard, “I was truly awestruck when I arrived for the first time on the outskirts of Paris. It was the beginning of autumn, and when I saw the russet birch trees, I immediately understood why the Impressionists painted as they did.” In Venezuela “the light was so harsh.” Soto had been unable to decipher the ‘Impressionist light’ in colour reproductions, and with the teaching of art history stopping short at Cubism, he responded by engaging with the only form of Modernism available.

“Cubism was an exercise in construction, in the ordering of planes, a tool that helped me to translate the tropical light.” The word ‘construction’ was a clue. After reaching Europe, he soon eschewed the practice of traditional painting, and extended his art into three (later four) dimensions.

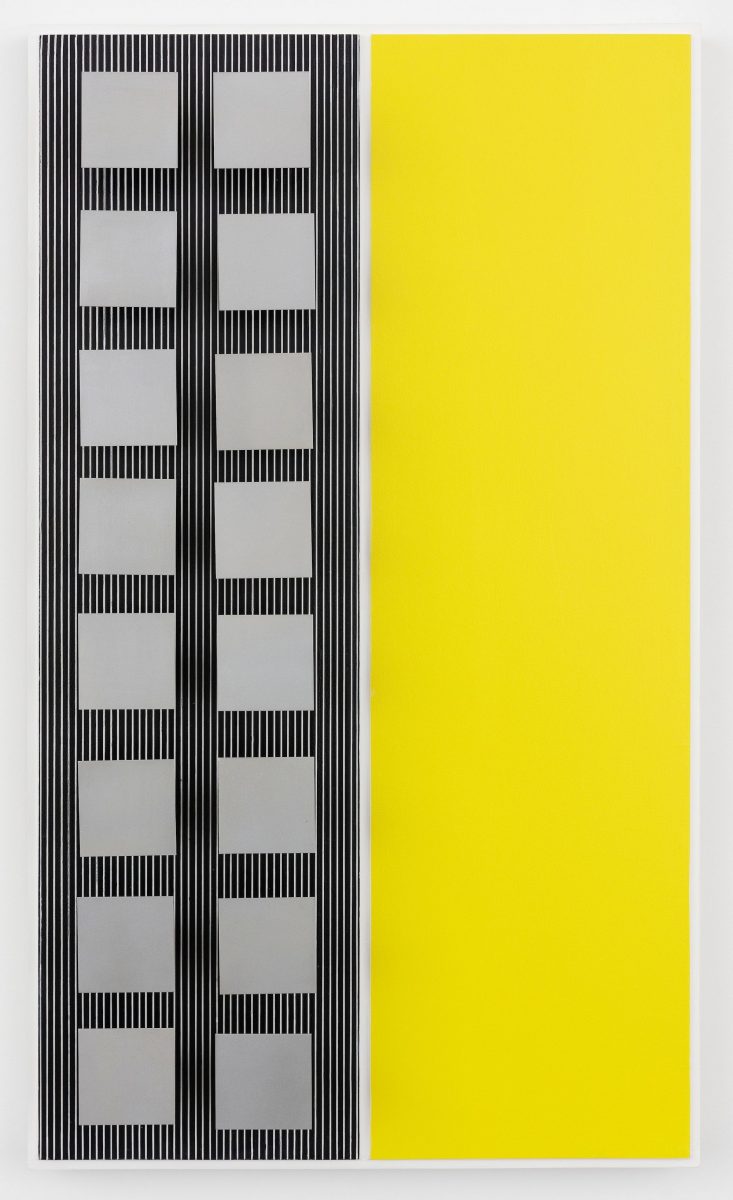

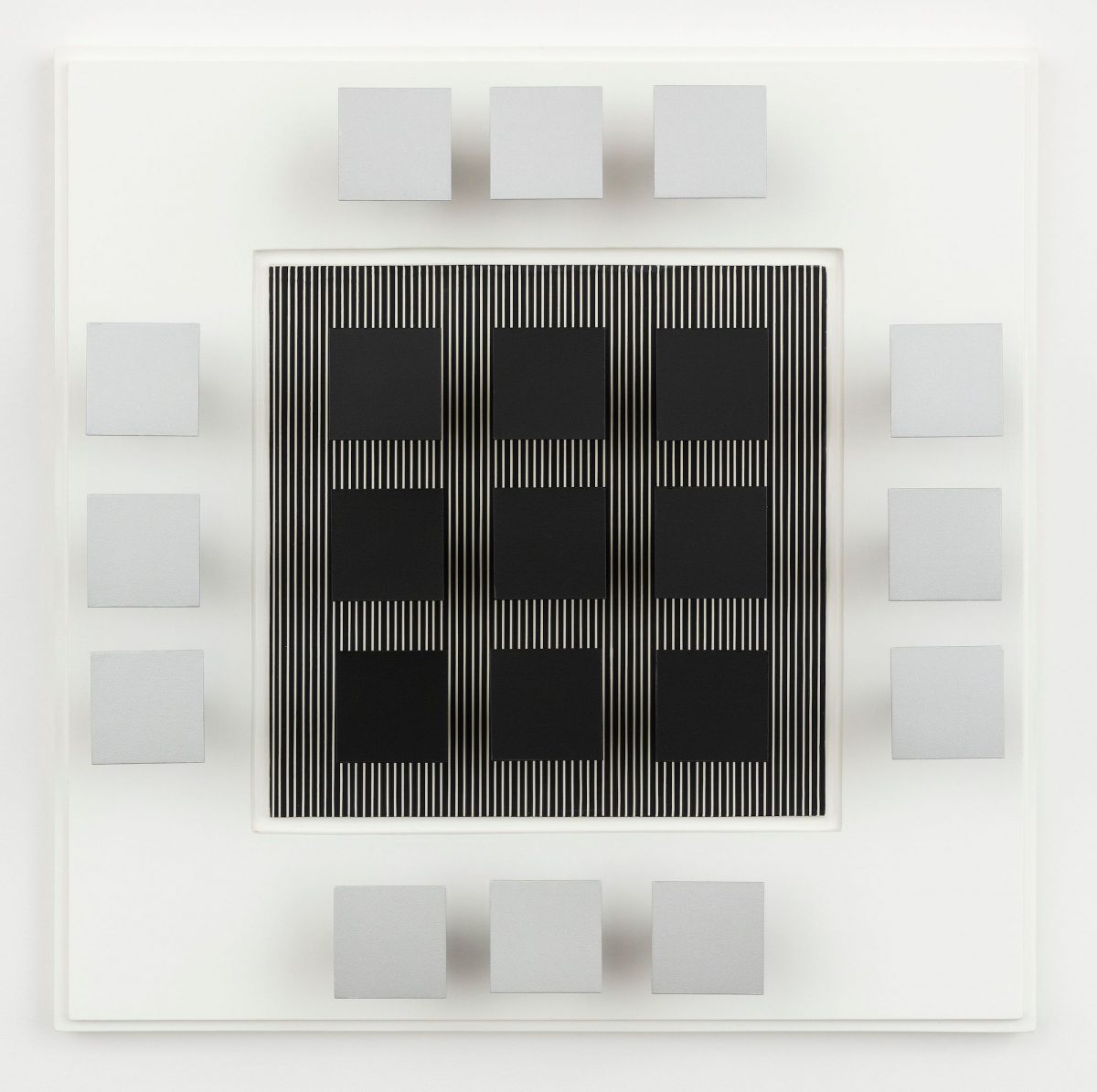

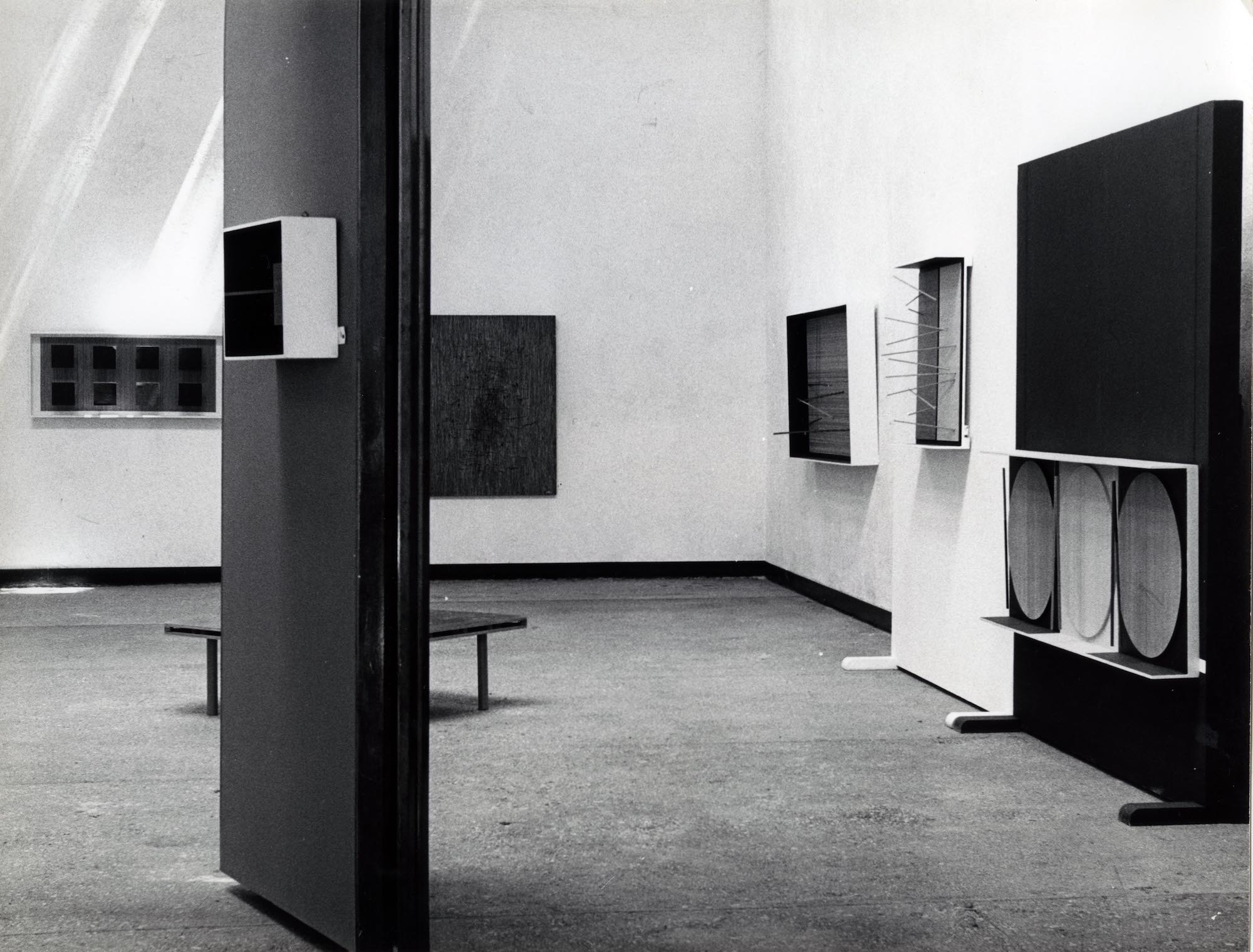

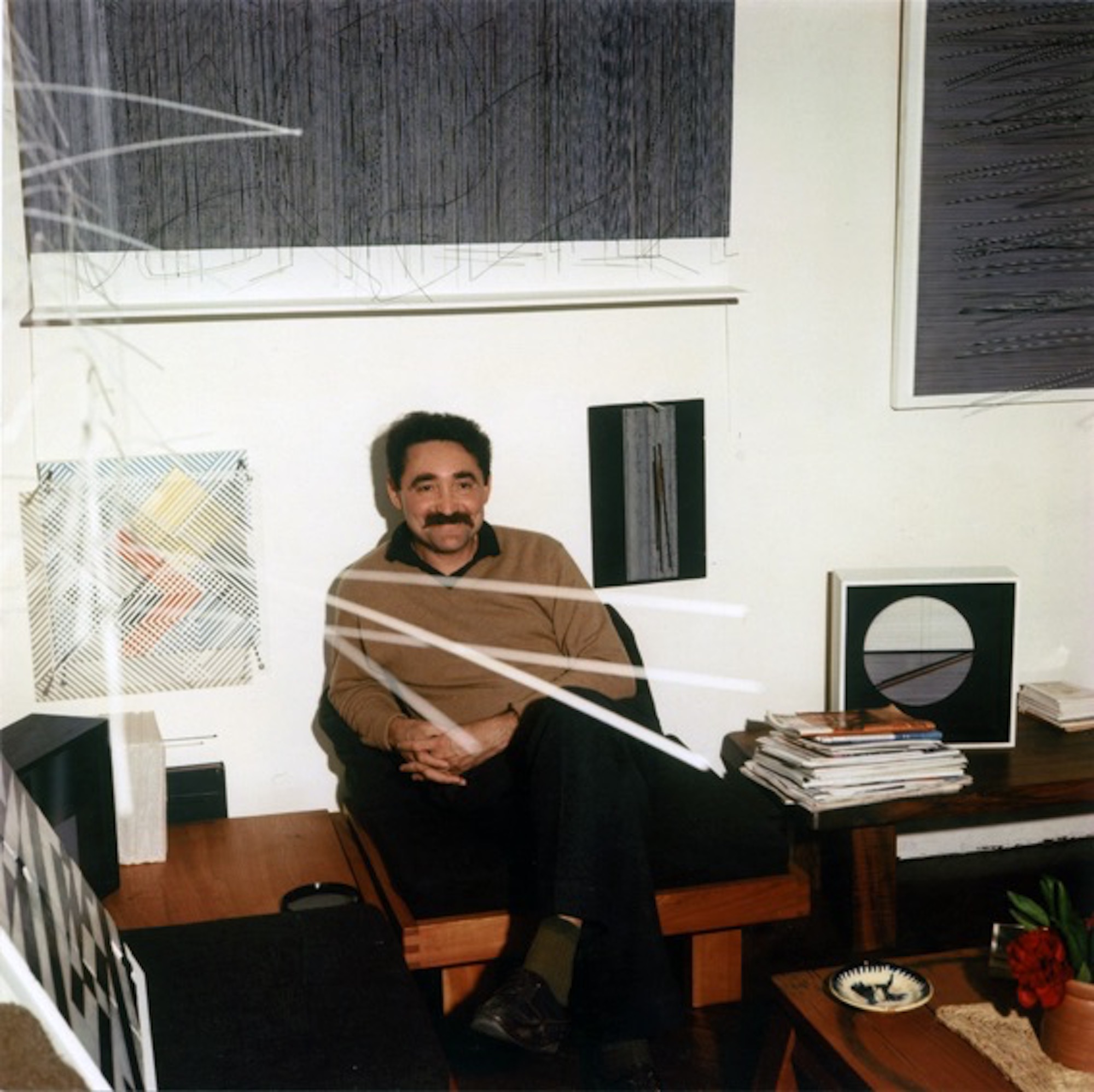

Perrotin gallery in New York is currently showcasing Soto’s work in an exhibition entitled Materia y Vibración, 1956-1974. Like many art critics, the gallery describes Soto as a pioneer of kinetic art, but it’s a tag that the artist himself consistently refused. Usefully, though, art historians have divided kineticism between artworks that move physically and those that appear to move when the viewer shifts their point of view. Soto’s artistic trajectory in Europe can be seen as a progressive refinement and elaboration of the principle of ‘apparent movement’.

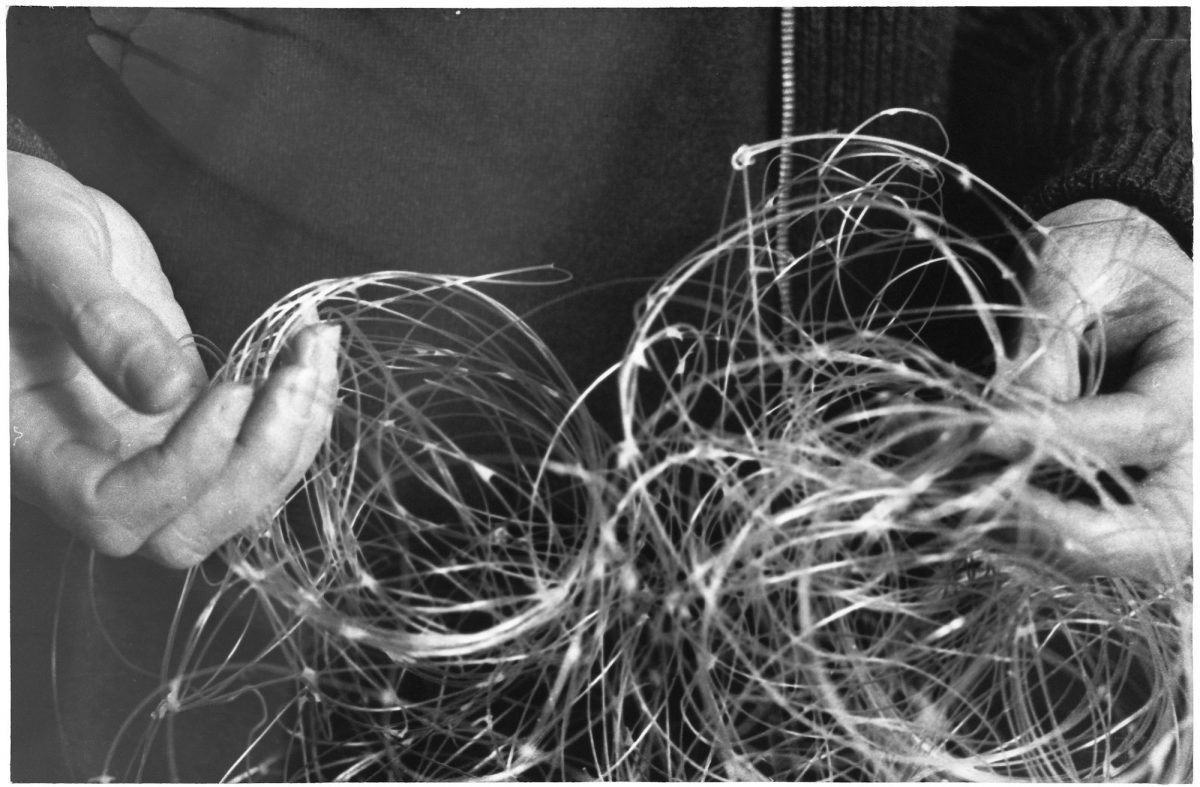

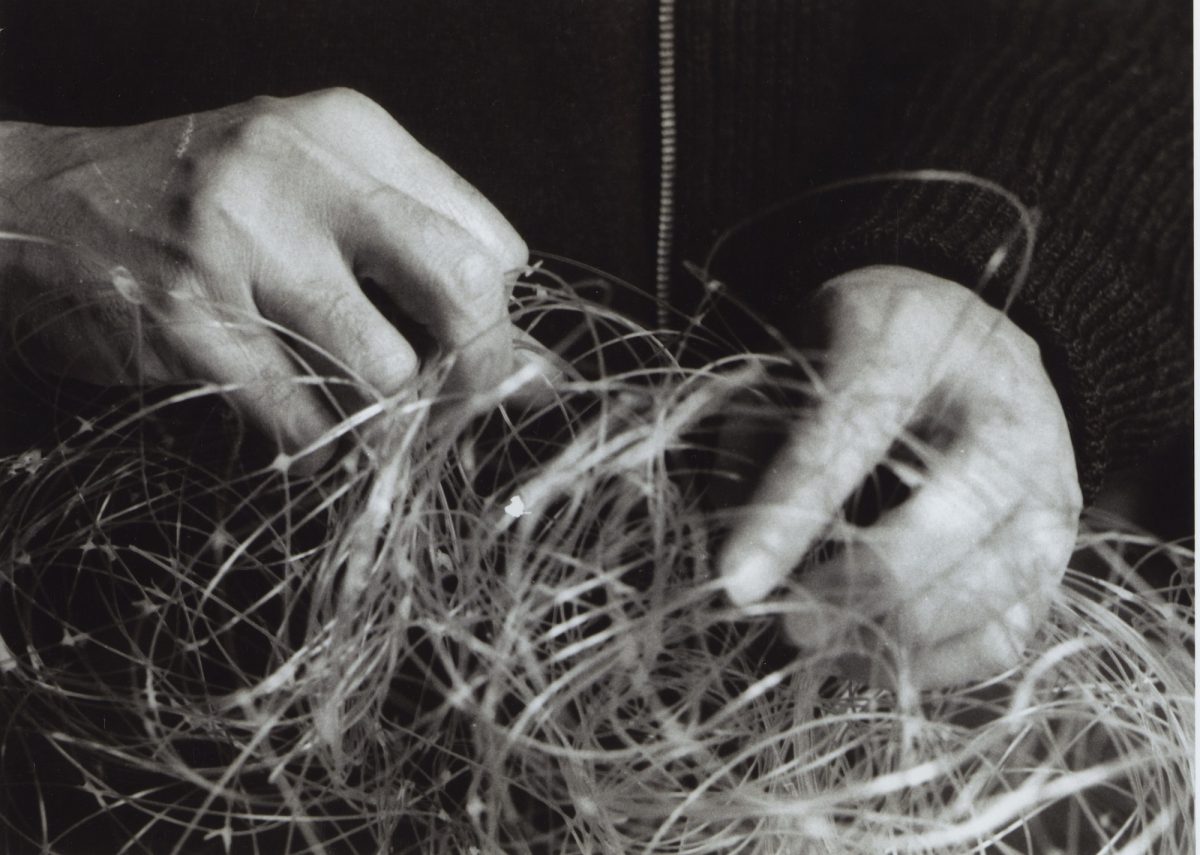

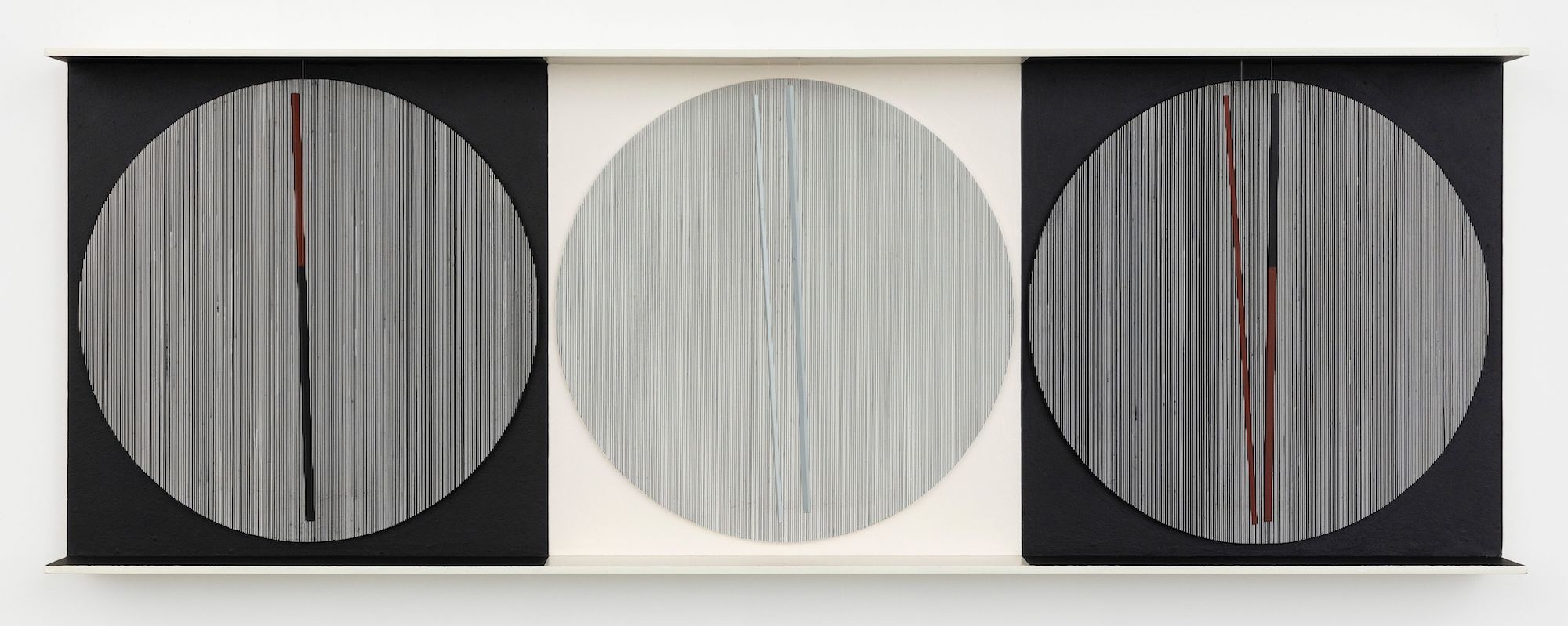

Take Cardinal, currently on display at Tate Modern. It consists of 45 steel rods, suspended by nylon thread, superimposed over each other, and set against a striated background of black, purple and white lines. Change position and the ‘moiré effect’ between the cascading rods and the horizontal gridding causes the assemblage to lose its form, to dematerialise.

Cardinal was part of a succession of similar works known as his Vibration series (the Perrotin exhibition includes works from this series that have never before been seen in the United States, including Venise, 1964). “What interests me is the transformation of matter,” he said. “Taking an element, a line, a bit of wood or metal, and transforming it into pure light”.

“Soto relentlessly reworked Modernism, merging light, movement and embodied experience to create previously unseen forms of art”

Born in 1923 in the former colonial town of Cuidad Bolívar, Soto was one of five siblings and left school aged 11 to contribute to the family finances by crafting lettering and store signs. By 16 he was painting as many as 50 posters a day for the town’s movie theatre, pictures made of paint to promote pictures made of light.

Three years later, a scholarship enabled him to enrol at the Escuela des Artes Plásticas y Artes Aplicades in Caracas, where the European avant-garde was a vibrant presence. Soto walked into the foyer to be confronted by a Braque still life displayed on an easel (a piece of artist’s equipment he had never seen before).

“Everything started to revolve around this: why was it a work of art?” he asked later. That spirit of enquiry pervaded the entire establishment, and many of Soto’s student peers (including the charismatic Alejandro Otero, a painter from Soto’s home town of geometric abstractions) would later reconvene in Paris and encourage him to join them there.

“What interests me is the transformation of matter. Taking an element, a line, a bit of wood or metal, and transforming it into pure light”

In France, Soto swiftly brought himself up to speed with the post-Cubist Modernism unavailable to him in Venezuela. He found pointers to the future in works by Alexander Calder, in Naum Gabo, in Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray’s 1920 Rotary Glass Plates (Precision Optics) and in the graphical illusions of Hungarian artist Victor Vasarely. He was also inspired by a pair of seminal books, László Moholy-Nagy’s Vision in Motion and Wassily Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art.

One of Soto’s biographers Alfredo Boulton described how Soto utilised another key influence: “the visual and tangible elements of Mondrian’s paintings were physically realised by means of structural elements which made space visible, tangible, mobile, active.”

Soto’s work often moved art historians and critics to hyperbole. Boulton described Virtual Suspended Volumes

(1976), a collection of 8,600 aluminium rods painted yellow and white in the new headquarters of the Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto, as “a tour de force domination of a monumental volume, situated within an immaterial void.”

The installation massively expanded Soto’s initial May 1967 deployment of hanging rods in the Denise René gallery, where he invited visitors to move into a suspended grid of thin plastic tubes, the first of his Penetrables, which he continued to produce for the rest of his working life. Echoes of their principle of immersive engagement can be found in more recent works as diverse as Olafur Eliasson’s fog tunnel, Yayoi Kusama’s Mirror Infinity Rooms (at Tate Modern from mid-May), Antony Gormley’s Blind Light and James Turrell’s Skyspaces.

Soto frequently compared his experiments with similar processes in science, though he was always made it clear that he operated at one remove: “If I had been a scientist, I would probably do the same thing: conduct my research on an essentially speculative level,” he said. The Parisian art critic Jean Clay preferred to see Soto’s investigations into “the instability of the real” as philosophical rather than strictly scientific.

“If I had been a scientist, I would probably do the same thing: conduct my research on an essentially speculative level”

Though Soto frequently endorsed such interpretations, stating for example that “For me, art is… a way of knowing the universe,” he kept his feet on the ground, affirming in an interview with Claude-Louis Renard for the catalogue that accompanied a Guggenheim retrospective in 1974 that “I still love music, and live a very casual life, seeing friends often. If I have any excuse to give a party, I give one.”

In his early days in Paris, he had supported himself by playing guitar in cafés and nightclubs. “I played from 11pm to 5am, slept until 2pm, then painted until 8pm,” he recalled. “That’s how I lived for ten years.” Even that music eventually become an artwork, recorded with musician Paco Ibáñez and issued on a CD in a plexiglass case designed by Soto.

By the time Soto died in Paris in 2005, aged 81, his art was held in the collections of major museums around the world. In 1973, the Jesús Soto Museum of Modern Art opened in Ciudad Bolívar in Venezuela (Soto’s home town) with a collection of his work, many wired to the building’s electricity supply so that they could move independently. In 1974, he was granted a retrospective exhibition at the Guggenheim: works from this, as well as from Soto’s contribution to the Venice Biennale in 1964, can also currently be seen at the Perrotin exhibition.

The critic Guy Brett once observed of kinetic art that “many of the instigators… came from the outer limits of the Western world, from what we call the Third World,” a description that accurately encapsulates Soto’s migration from post-colonial periphery to the creative metropole. In making that journey he embraced a Modernism he could only imagine in Venezuela, one that he went on to relentlessly rework, merging light, movement and embodied experience to create previously unseen forms of art.

All images © Jesús Rafael Soto / ADAGP, Paris 2022. Courtesy Atelier Soto – Paris

Steve Taylor writes about cities, music and urban culture. He recently started a PhD on underground music scenes and the future city

Jesús Rafael Soto, Materia Y Vibración, 1956 – 1974

Perrotin, New York, 5 March – 16 April

VISIT WEBSITE