The fourteenth edition of the Lyon Biennale–which will run from 20 September until 7 January–has been curated by Emma Lavigne, the director of CentPompidou-Metz, which is located in the East of France as a branch of the famous modern art museum in Paris. Lavigne has been invited by the artistic director of the Lyon Biennale and director of the MacLyon museum, Thierry Raspail, to think about the term “modern”, exactly as Ralph Rugoff, at that time the director of the Hayward Gallery in London, was invited to do two years ago. The event, entitled Floating Worlds, will be displayed in two main venues in Lyon; the MacLyon museum and the Sucrière building, the latter of which was once an industrial sugar factory dating from 1930. Some works will be lent by the Centre Pompidou in line with the museum’s fortieth anniversary, but the main selection of more than fifty artists is brand new and quite fresh. This Biennale is divided into five sections: Ebb and Flow

, Ocean of Sound, An Archipelago of Sensation, Electric Bodies, and Inner Cosmogonies.

I spoke with the curator.

The artistic director of the Biennale, Thierry Raspail, questions the term modern. Do you want to deal with art history in this edition?

The form of the Biennale may not be the best territory to look in an elaborate way at art history but it indeed aims and wishes to widen the concept of the modern, to take it out of its western envelope, to crack it open and to biomorph it in order to follow the process of transformation and reappropriation that happens everywhere else in the world. Therefore, the exhibition of several works by the Brazilian artist Lygia Pape will be the entry to the Biennale section Archipel de la Sensation [An Archipelago of Sensation], dealing with this modern common heritage and its diffusion that needs to be looked at with a critical eye. Jill Magid will, in particular, reenact this issue. Ever since 2013 she has been looking for the archives of Mexican architect Luis Barragán and Tapete de flores–that will be produced specially for the Biennale–questions the impossibility of her research. It also questions our common heritage.

What do you think of postmodernity?

The concept of the postmodern hasn’t been at the core of our reflection in this Biennale. I have preferred to look for another form of modernity in relation to the openness of artworks, as it is defined by Umberto Eco in the book L’œuvre ouverte (1965), a state of the world that is suspended and in constant mobility. To my mind, it best suits today’s art scene.

Do you question the achievement in the artwork?

The closure or achievement of the form in art corresponds only to a part of art history but not to its totality. The second issue that refers to Duchamp’s way of dealing with openness and spatiotemporal fragmentation interests me more and corresponds best to the question developed by the artists I work with usually, whether they are present or not in the Biennale this year. I think in particular of artists like Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster whose retrospective I curated last year at the Centre Pompidou in Paris or Pierre Huygue who deals with live situations evolving with the exhibition.

How does language and poetry mix with the artworks in this biennale?

Language as an immediate plastic expression or as a language that feeds the world of some artists like Anawana Aloba, Marco Godinho, David Medalla and Davide Balula, will be an important red thread in the exhibition, strengthened by political statements in the shape of the haïku of Marco Godinho’s Forever immigrant (2012), stamped on the façade of the Sucrière building in Lyon. There will be some more historical statements linked to the conceptual scene of the 1970s–especially the work of the Polish artist Ewa Partum. In her work Active Poetry, Poem by Ewa (1971–1973), cutout letters are actually scattered in the public space or in nature, shuffled or picked up by people or even gone with the wind, creating new poems, or a new language, disappearing little by little in the landscape. This artistic gesture also referred initially to the authoritarian discourse at the time of the People’s Republic of Poland. The film of this performance will be shown in relationship with Brazilian artist Rivane Neuenschwander’s recent research, Migratory Words (2006), exploring the language of protest with words written on some photographs of French social conflicts. This work is like a poetic and global map of resistance.

What do you actually refer to in terms of flow?

I wanted to catch the echo of Baudelaire’s way of thinking in his definition of what is modern such as things “transitory, fugitive, contingent, the half of art while the other half consists of the eternal and the immobile”. These words resonate with the acceleration of the flow at a time of ever-quickening globalization and of the world liquidity and identity as analyzed by the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman. He describes contemporary society by a constant mobility generating the dissolution of relationships and of identities, the uprooting of the hypermodern. The flow is what connects individuals, what allows them to communicate, to get closer, and at the same time it may well uproot and displace them. What interests me in this context is to see how some artists have used this flow, whether it is Ewa Partum’s action poetry, the transistor radio in Babel by Cildo Meireles, Christodolous Panayotou’s capital-flow in his paintings made of demonetized bank notes, or the uprooting of human beings in Anawana Aloba’s work. And I might also evoke the work of the artist Dominique Blais who is interested in making visible what is invisible, electric and sound flow–his statement is related to the question of immateriality and energy.

Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, M O R P H O © Daniel Steegmann Mangrané

How do you deal with nomadism in this biennale?

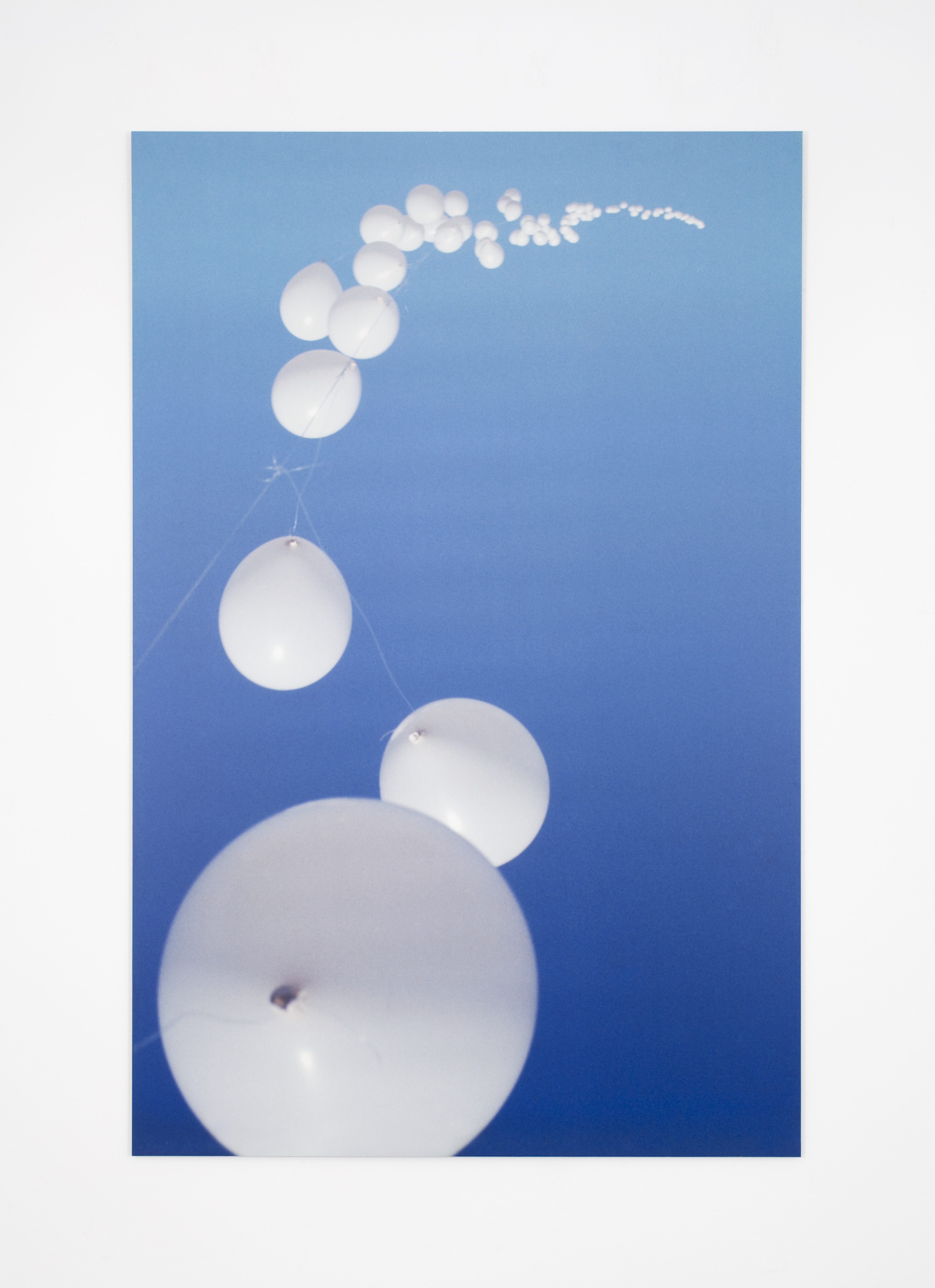

A third place will be located between the MacLyon museum and the Sucrière building: the radome of Richard Buckminster Fuller. It was developed in the 1950s as a geodesic dome. It may be built in a very short time and can be moved easily. It generated new modes of ecological and nomadic housing and new alternative human communities. Notably, a lot of artists’ works in this Biennale deal with a poetry of nomadism–for instance, the loop video En suspens (…) (2014) by Julien Creuzet or Prachaya Pinthong’s Epheméral Cinema that will move from place to place in Lyon. Robert Breer’s Floats and Rugs will also be shown in the exhibition, moving with indiscipline, weightlessness, slippage, and fluidity.

How did you select the emerging artists?

It is all about exchanges, new directions that make me want to explore further works I have discovered. Each time it is a different narrative and context. For instance, I discovered Yuko Mohri’s work during a trip to Japan. Her works deal with autonomous ecosystems, made of diverse mechanic elements, reconfigured by the artist herself. The improvised conception of these ecosystems questions intangible phenomena: gravity, magnetism, or thermic variations. She is very inspired by some French figures of the modernity such as Duchamp or Satie and she proposes two projects for the Biennale that revisit this heritage.

How do you see the international context of the Lyon Biennale?

The Lyon Biennale has been able to maintain its specificity while other biennales multiply all over the world. It remains a territory and an experimentation of freedom, and it has been run since the creation of the Lyon Biennale by the same team that are in a position to remember previous editions. Indeed, the dialogue with the MacLyon museum and the works from its very beautiful collection is also a main asset. The Lyon Biennale has been a model for smaller biennales in the world with no huge budget. Its example proves that such events can exist and keep their experimental form and specificities. It was a model for Dakar and Koichi in particular.