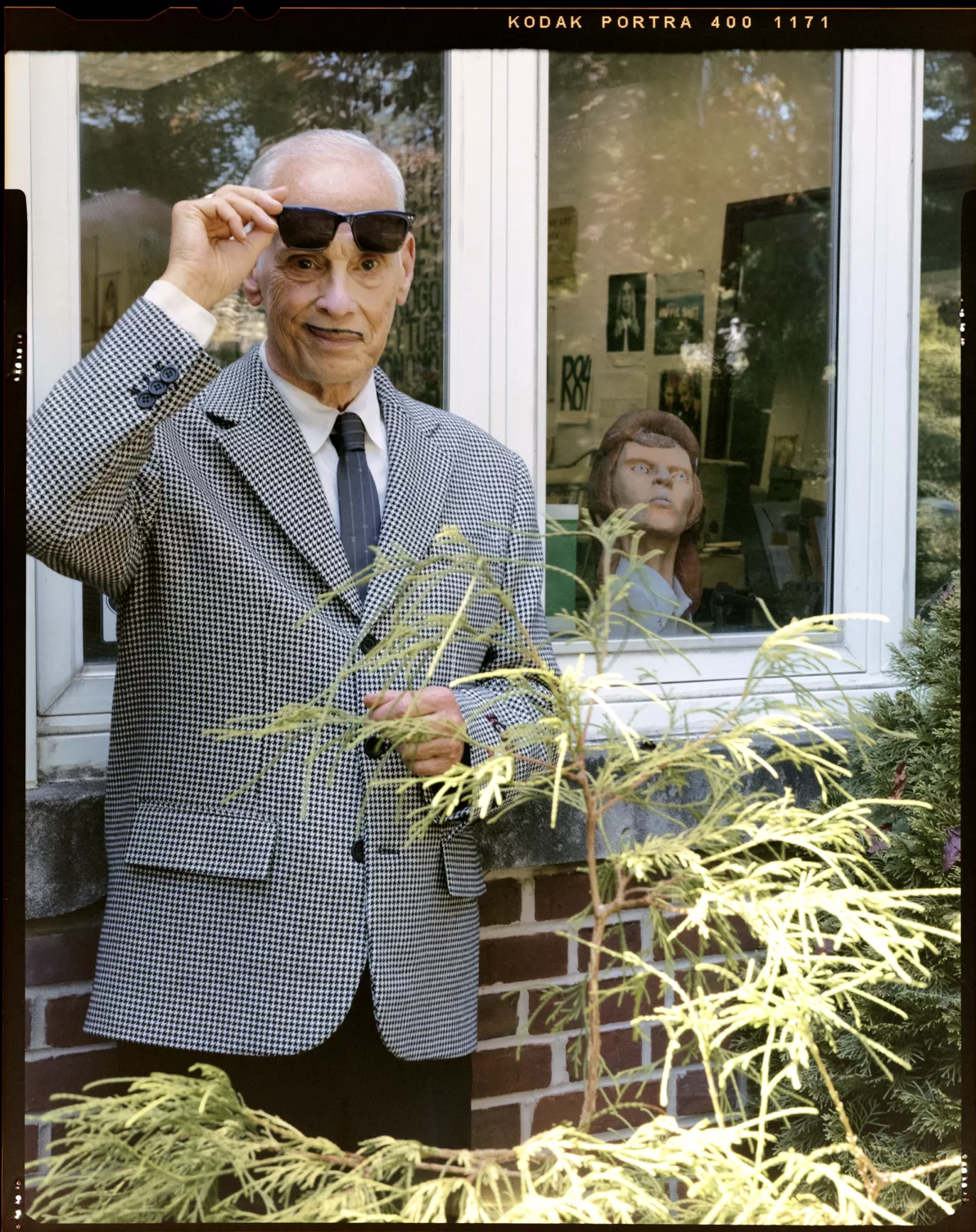

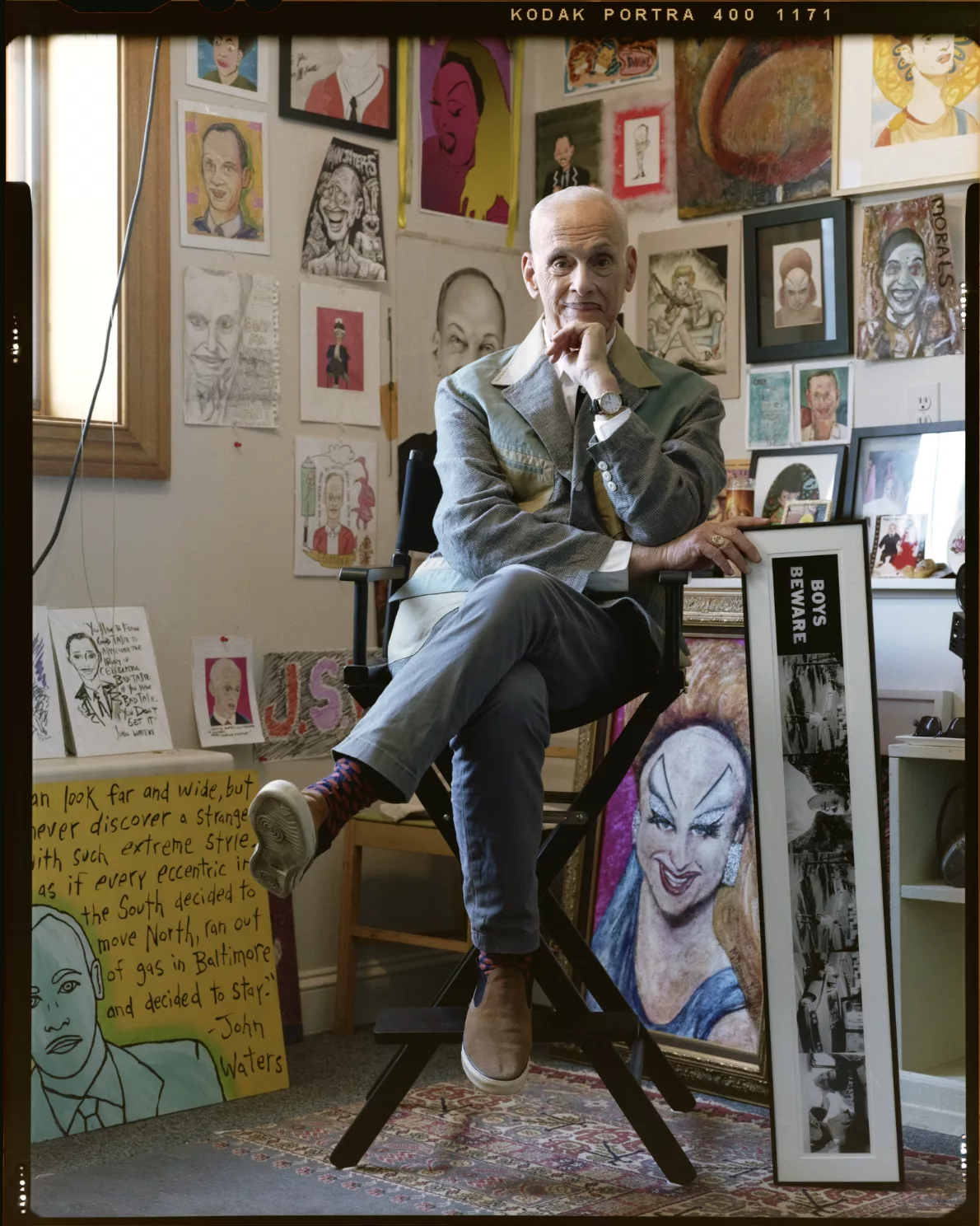

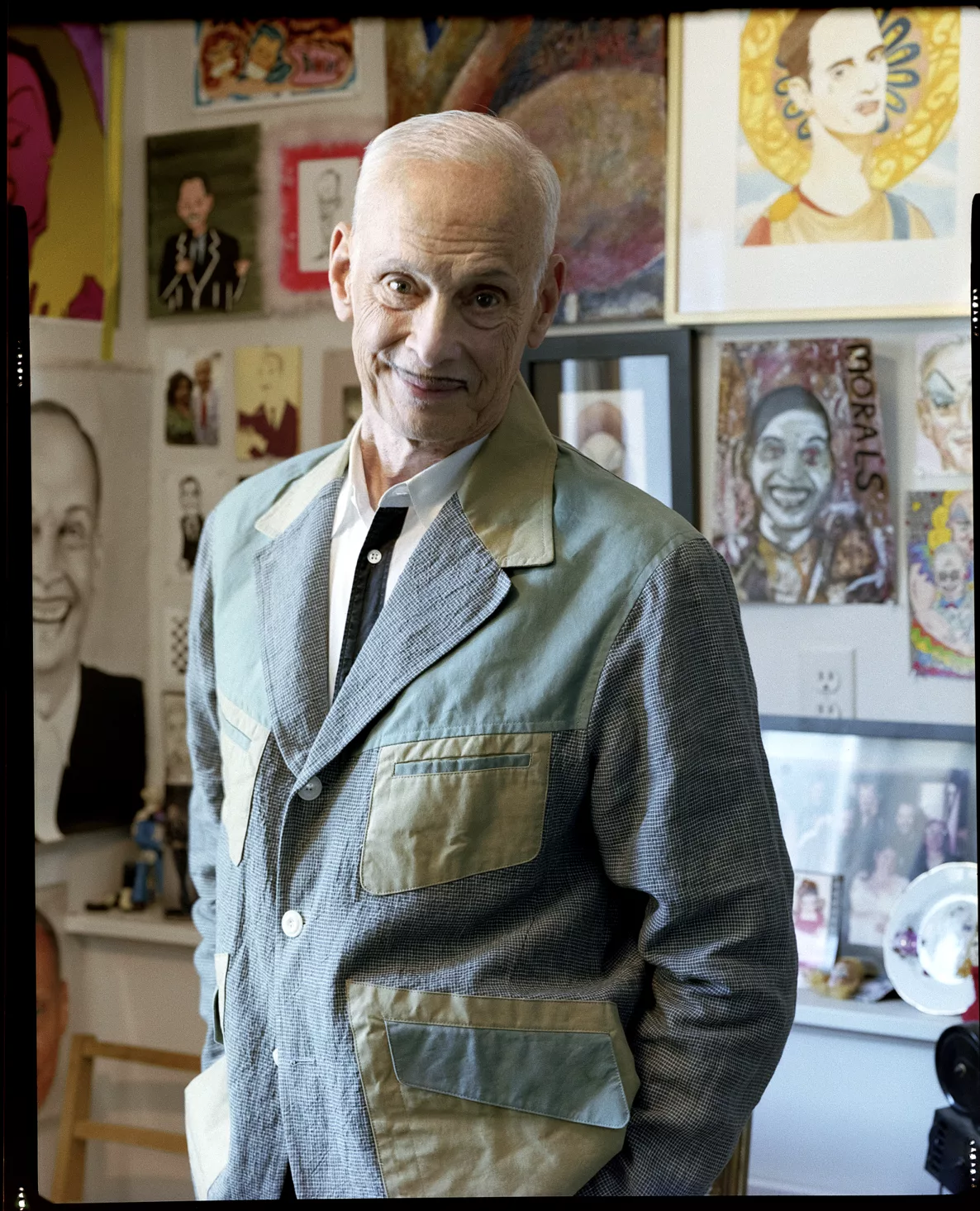

John Waters Art muses on little movies and scary sculptures with Elephant writer Kristen Hileman.

Icons seem to have an affinity for icons. In a recent conversation, John Waters, the celebrated polymath of subversion and parody, began reflecting on more than three decades of making visual art with a story about his first encounter with the late, great Tina Turner. He went to an early 1960’s concert. “Tina, Ike, and the band arrived in a broken down green school bus. Tina was raw. She had a mustache and wore a ratty mink coat…she had an aggressive, crazy trashiness. They performed a jaw-dropping, soul show; the best rock-and-roll show I’ve seen in my life.” Gritty and fierce, Turner was a major influence on John and his muse, Divine, Waters’ teenage friend who went on to star in Pink Flamingos, Hairspray and many other of Waters’ classic cult films shot in their hometown of Baltimore. Waters even recalls Divine wearing the same shoes as the legendary singer—gold Springolators—in the film Mondo Trasho, 1969.

“I wanted to capture that Tina in my sculpture Control, before she moved to Zürich and became like Jackie Kennedy,” Waters continues, but that also meant addressing her abusive husband Ike Turner. In the 2009 work, Ike plays puppet-master, holding Tina’s strings and evoking the tortured lyric, “You control every movement,” from the couple’s 1963 song Letter from Tina. The figures are uncanny, doll-like but with hyper-real flesh and hair, achieved through the contributions of fabricator Tony Gardner, a special effects genius who created Chucky, the terrorizing doll of the eponymous horror film franchise. At about one-third to one-half human scale, Ike and his intimidating pompadour loom over the miniature, albeit leggy Tina. While the effect is undeniably uncomfortable, the diminished scale and frozen poses are visual tools for introducing a therapeutic humor into the situation, one that exposes the complexity of the couple’s relationship and almost literally allows us to grasp the violence and manipulation behind their powerful music. Waters’ choice of scale also leaves room to imagine a later Tina, one whose extraordinary success as a solo artist ultimately eclipsed her years with Ike. Human experience is anything but straightforward in the Waters’ universe.

“Ike’s pose was inspired by a cover illustration for Witness to Evil, a book about the Manson family with Charlie pulling the girls’ strings.” Serial killer Charles Manson is another significant character in Waters’ wild iconography. In a series of photographic works, spanning 1993-2003, the artist juxtaposes Manson’s courtroom looks with the accessories and outfits of Divine, B-movie actress Dorothy Malone, Richard Gere, and Brad Pitt to propose a disturbing similarity of style and star appeal between good and evil. Fame, its moral ambivalence, and the frequency with which people desire it, are ongoing themes. Waters speculates that “whether they know it or not, regular people who aren’t in show business feel depressed every day because they aren’t in show business.” As an antidote, he created the piece Liz Taylor’s Hair and Feet, 1996, a rectangle of Elizabeth Taylor’s hairdos atop seven shots of her feet, appropriated from various movies. Waters imagines people positioning themselves in the middle of the piece to try on the screen goddess’s celebrity, like a funfair attraction. In showing the work, he has found many a compulsive fan who can identify the source movies from Liz’s raven locks alone. When Waters met Taylor in the late nineties, joining Tab Hunter and Johnny Depp as guests at one of the actress’s parties, he found her to look a lot like Divine. The resemblance, which Waters sees as a compliment, was already the subject of 1995’s Doubles. Beyond achieving glamour of a most elite order, Waters admires Taylor for putting her celebrity to groundbreaking advocacy work in the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “She is a patron saint of the gay community, as far as I’m concerned,” Waters says.

Playdate, 2006, another outlandish sculptural collaboration with Gardner, returns to the sinful side of the Waters’ pantheon. Here, the adult faces of Manson and Michael Jackson are placed a top infant-size bodies, producing creepy adult babies. Crawling Michael, wearing a pink onesie, lifts his arm toward a mesmerizing Manson. When asked whether he is assembling a rogues’ gallery through his art or developing a taxonomy of evil that speaks to his long left behind Catholic upbringing, Waters replies that he often makes work about behavior that is beyond comprehension. “My position is the opposite of Catholicism, which claims everyone is born guilty. That is the worst thing you can tell a child. I believe everybody, including Michael Jackson and Manson, is born innocent, and then something happens. Something happens to all of us. People don’t necessarily make a choice to act badly. That’s why I’ve always been interested in behavior that I don’t understand. If I didn’t do all this, I think I’d be a defense lawyer or psychiatrist.” He adds, “Who knows if Michael and Manson had an early playdate, maybe things would have been different, maybe they would have equaled each other out?”

Like most of the artist’s sculptural pieces, Playdate comes in an edition of five, with one artist proof. Waters gleefully notes that one collector told him that she keeps her edition in the closet to scare her grandchildren. For Waters, that art can be scary is a good thing. He sees it as art’s job to wreck things, including one generation of art replacing the next from Abstract Expressionism to Pop to Minimalism and so forth. Watching his childhood playmates get agitated over a reproduction of an abstract painting by Joan Miró that he brought home from The Baltimore Museum of Art gift shop, was foundational to understanding art’s power.

Perhaps Waters brought this renegade motivation to the puppet shows he performed at children’s parties in his suburban neighborhood, looking not much older than he does in John Jr., 2009, a sweet pastel portrait commissioned by his parents that the artist later mustachioed with Duchampian flair. (Waters is quick to clarify that he used hand puppets, not marionettes.) Still a teenager in 1964, Waters found his medium of film and talent for provocation, packing an interracial marriage with a Ku Klux Klan officiant into the 8 mm short Hag in a Black Leather Jacket shot on the roof of his parents’ home. The film is a good candidate for the official launch of the aesthetics of trash that have brought the artist so much acclaim, as well as the moniker “The Pope of Trash.” (This is also the title of a career-encompassing exhibition devoted to Waters’ moviemaking at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles on view through August 4, 2024.)

Four years later, he made his first 16 mm movie, Eat Your Makeup, for which he restaged the Kennedy assassination on his family’s quiet residential street with Divine as Jackie frantically clambering in a convertible. Waters appropriates himself in Zapruder, 1995, a sequence of 24 frames from Eat Your Makeup that reveals how astonishingly well the young director and his counterculture cohorts understood the historic impact of what Waters calls “the most famous snuff movie ever” and merged the tragic fall of the Kennedy era with their own new narratives of gender and sexuality.

Indeed, the origins of Waters’ visual art lie in revisiting his earlier movies. In 1992, a few years after Divine’s death, the artist sat in the dark, rewinding and fast-forwarding Multiple Maniacs on a VCR as he shot hundreds of pictures on a 35 mm Nikon in an effort to create a still of the actor that had not been taken during the 1970 production. He titled the result Divine in Ecstasy. A later work, Dirty Divine, 2000, epitomizes how formal qualities, process, and content come together for Waters in an off-kilter way that uplifts imperfection and makes everything wrong right. Relying on his maniacally attuned eye—he describes his behavior as that of a crazed fan—Waters landed on the moment in a video tape of one of his “early, tawdry celluloid atrocities,” he can’t remember exactly which one, when the transfer from film to video had preserved the scratches caused in the final frame of a reel that had not been taped properly and flapped up against the projector, getting scratched and otherwise abused. He shot that fraction of a second off his CRT TV screen, not only rescuing a fragment that should have been cut off and thrown away, but degrading its resolution further. Waters observes that the more a film print was played—the more popular it became or the more it progressed toward cult status—the more likely it was to become dirtied and eaten up by the projector. He appreciates this wear and tear that comes from use.

In this sense, Waters’ reverence for trash not only encompasses the transgressive value of upending cultural hierarchies, but also viscerally calls attention to the things that people wear out through their attractions and, at times, irrational appetites. In today’s world of high production values and slickly designed surfaces, Waters’ elevation of pathos can be a surprising, humanizing reminder of the blemishes that we cause and that we all develop.

Waters often refers to his photographic works as “little movies.” They are storyboards and vignettes that he can re-edit not only to emphasize images from his own catalogue, but to twist plotlines and highlight perverse details from other films, such as the moment a baby bursts into flames in the 1961 Connie Stevens-Troy Donohue teen pregnancy melodrama Susan Slade. “A publicist would never choose that for a film still!” exclaims Waters about Slade 16, 1992, his reimagined version. Wicked Glinda, 2003, spookily captures a dissolve in the Wizard of Oz from Margaret Hamilton’s Wicked Witch of the West to Billie Burke’s Glinda. This hybrid character shimmers between cloyingly good and very, very bad. “They’ve become one person, a new heroine who switches back and forth, a schizophrenic. That may be a more interesting character wondering around Oz,” muses Waters.

Thinking of Waters’ visual art in terms of genre (he encapsulated low budget horror flicks in 1995’s The Tingler and moody arthouse existentialism in 1994’s Foreign Film) and character studies seems apt. In 2014, he developed “Bernice”, a fictional librarian cum Robin Hood offering free home delivery of pornographic paperbacks, gruesome true crime stories, and other censored books to the scattered members of her book club for Carsick, his chronicle of hitchhiking across America at the age of 66. At the same time, Waters created Library Science #1-10, as if to curate a highlights exhibition from Bernice’s stashes.

In actuality, these covers of novels paired with their “adult versions” come from Waters’ own collection. Erskine Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre meets its match in God’s Little Faker, while Ian Fleming’s children’s story, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, is brilliantly reworked as Clitty Clitty Bang Bang. Mass-marketed in the 1960s, the novels’ covers, particularly the naughty ones, manifest the signs of use to which Waters is so drawn. Scuffs, creases, and crimped corners suggest heavy handling and the effects of sweatily secreting the books under sheets and into hiding spots, where among other things, they were safe from being burned, a fate met by many of the titles, making remaining copies rare, according to Waters. The books convey a titillatingly intimate absorption of media, not unlike the artist’s act of sitting in the dark alone snapping pictures off of his television. It’s a quality lost now that we multitask while listening to podcasts played back at highspeed. The colors of the cover designs are also striking: crimson, hot pink, spoiled-butter yellow, and pea green constitute a lurid rainbow of sexual proclivities.

“Pimple queen,” however, is not among these predilections. Instead, Waters explores the fetish in another work, a piece that also serves as an ode to one of his favorite directors, Pier Paolo Pasolini. Waters stalked the footage of the young actors in Pasolini’s oeuvre, scanning for a typically unloved detail…pimples, which were a turn-on for the Italian auteur. If ever there was an exercise in close-looking, this was it, with Waters scanning film after film, shot after shot on his TV screen to find millimeters-big pustules. “Like snowflakes, they come in a million shapes,” the artist quips. He aggregated these discoveries in 21 Pasolini Pimples, 2006, which, he concedes, is not infrequently mistaken for nipples. It might just as easily be confused with abstract painting, in its muted tones and blurred gestures, a similarity not lost on Waters, a longtime collector of contemporary art, yet another subject he takes up in his own practice.

“I always make fun of what I love, that’s why I’ve lasted as long as I have” claims Waters, who lampoons Minimalism in his mock travel advertisement, Visit Marfa, 2003, which promises rigorous bonfires and a Carl Andre look-a-like contest. “I love the elite part of the art world. It’s a secret club with rules to learn. You have to wear clothes, talk, and spend your money a certain way. All the things that people hate about it are why I like it.”

Waters makes some headway in decoding art world etiquette with 2006’s Artistically Incorrect #1-14, a series of epigrams, such as “Reserves are for pussys” and “See you in Basel, bitch” that reveal what art insiders wish they could say if high class manners and profit motive did not restrain them. Yet, the artist doesn’t chafe at the commodification of art. Given his gifts of invention as a writer and imager-maker, as well as the carnival barker aspect of his persona, he appreciates it. “It’s a magic trick. Mike Kelley can take a dirty blanket and an old thrift shop stuffed animal with its eye missing, and it’s worth a million dollars. That’s magic…that is what art is: taking one thing and making it something else by just saying it, or showing it in an interesting or original way. And the truth is, if you get away with it, it is actually transformed. I find that delightful.”

To be clear, cynicism is not at the heart of Waters’ work. Instead it is his interest in the strange behaviors of people and how they organize themselves around fascinations, fetishes, obsessions, some more specific and rare than others. For instance, you may need to do an NSFW google search of the title of 1996’s Shrimper to understand what subculture that piece contemplates. Waters’ art is more about curiosity than judgment. There is a note of empathy in the artists’ voice as he discusses his 2007 Study Art Sign series, prominently featured in the 2017 Venice biennial by the distinguished French curator Christine Macel. Over the course of about thirty years, Waters had passed a sign on the streets of Baltimore advertising an art school with the words “Study Art for Profit or Hobby. He photographed it, then recreated it as a sign and fabricated several pithy new iterations like “Study Art for Prestige or Spite” and “Study Art for Breeding or Bounty.” In the world of museums and blue chip galleries, “profit and hobby are the two worst reasons to give for making art. But that sign was so beautifully innocent. I wasn’t mocking it. I was marveling about a kind of art that was so different from the art that I was participating in.”

Written by Kristen Hileman