John Akomfrah is one of six artists to be shortlisted for this year’s Artes Mundi Prize, which focuses on practices that have an emphasis on contemporary social issues. Akomfrah is internationally recognised for his epic films, focussing largely on African diaspora in Europe. He was awarded an OBE for services to the British film industry in 2008.

How do you tend to get to ideas when you begin work on a new show or body of work? Do you typically come to the general concept first or is it more a case of going through footage and maybe finding two or three pieces that spark an interest?

Inevitably, the way it works now is that you’re asked to submit an idea beforehand, so I try to be suggestive but vague, with a clear sense of what thematic elements will be in there. If I start foraging in archival material and can’t find the right thing, then that’s when I decide: I’m going to have to make this. If I can find elements in archives that speak to it then it’s a question of how and what we can use to bear witness to what the archival material has. This is almost wholly when the piece is going to be a marriage of archival and non-archival elements—that’s not always the case.

As you’re making the films do you have quite a firm structure in mind?

Oh no, no! I try to be open because I think each thing we end up working with inevitably has resonance and implication and value all unto itself—and they’re not necessarily things that I impose myself. So the trick really is to be patient with the material and try to listen and watch and see what it is that it is saying to me first. Instead of asking it questions, you know: Why don’t you say this? Or that? I need to know what its properties are before I can do that. They aren’t necessarily fixed qualities either, but they are implications that are already present before one goes off into the abyss.

When you’re putting a film together—obviously there is that sense that there isn’t a strict meaning or narrative to your films—do you like to feel the looseness of the piece yourself? Do you ever get to a point where it feels to rigid or confirmed for you, that you know too much and you need to open it back out again?

Yes. It is what I call the dramaturgy of the piece, that it has that element. I’m starting off with a set of inquisitive points that I’m just trying to confirm. Am I in the right space with these questions or interests? At some point they solidify and things start to confirm: Yes we are speaking to you. But the trick is to not listen too much to that, because the second act is that I begin to hear what I call the siren calls of the archive. At that point I have to do two things. The first is obviously to hear it and acknowledge that I’ve heard it, but then to say, well actually I have other questions that I’d like you to consider. In a very humble and gentle way. These are not authoritarian movies but you have to seduce images to consider other options for their existence. Once they begin to be seduced and take on the promise of those options, then things start to loosen up again.

Since you began working the technology that surrounds your practice has developed a great deal. Has this changed the way you work drastically? Is it a constant race to keep up?

I remember in ’82, ’83 when a number of us first got into making sound pieces and it would take all night! You’d have to run around for days to get enough reel-to-reel recorders. Now if I want to create a loop I can do it in ten seconds. That acceleration of the process has implications, not all of it necessarily great. There’s a kind of shrinking of the space of thought and reflection which is not great. But it was very clear even in the ’80s that we were not celluloid people. It was clear to me that the process by which celluloid comes together just takes too long. So the practice always seemed to be premised on this utopian moment to come where there would be another way of doing things, a way of avoiding labs and studios and I feel grounded by what’s happened rather than estranged.

Looking back at the ‘80s as well, you founded the Black Audio Film Collective which challenged the way black British communities were seen on screen and in the media. Do you feel things have changed since then for the better, has the conversation moved along?

I mean, I think things have changed. If you take a very obvious example, there were people of African and Asian descent working in cinema and television at the time, but nowhere near on the scale they are now, and the diversity. I come across people all the time from drama, documentary, feature films, the range is amazing and one wants to acknowledge that as a genuine seismic shift in both our understanding of how images work and also who is involved. But the problem with the question of diversity is that you can’t say things have improved without saying: job done. The job’s not done, that’s for sure! Are some of the issues that we were trying to raise—about the nature of the image, how the image can appear to be dealing with the fullness, the complexity of Afro diasporic and Asian lives—still important? Yes. You only need to see the furore over the Oscars to know that these are all going questions. A lot has been achieved, my life is in no way the life of my children when it comes to images at all. But there are questions about access, inclusion, diversity, which are as relevant and important in their lives as they were in mine. They should have the room to ask the questions, even if they get different answers.

In slight contrast to that there’s the migrant crisis—which you have covered numerous times in your work—which seems to have got worse and worse in recent years, especially in our attitudes towards the crisis itself and the people involved.

One of the things that whole Brexit affair seemed to suggest is that questions I thought we had solved are very much alive. If you told me ten, fifteen years ago that we’d be revisiting these questions of strangeness, foreignness and alienness again, as if we had never seen and dealt with these questions, I would never have believed you. All of that makes me think that you can never be too complacent or too triumphant with what it is that you think has been achieved. I really wanted to stress to people the extent to which societies create things. These kids are rioting. Why are they rioting? They’re rioting because they live here. They’re not just gangsters, or criminals. You find yourself having to say the same things about the people trying to migrate here. You hear journalists calling them rats and think: Can we just get something right here, these people are fleeing turmoil and chaos, largely and in part to do with us. Can we just acknowledge that before we steam off into blame? In the ‘80s we were trying to make a case for causalities, for connecting things. I find myself back in that same space again now.

In a lot of your work there is a merging of old and new, past events and current events, and it actually fits that cyclical way of thinking and developing. There’s a common idea that things progress and move forwards constantly through history, when in fact we bump up against the same ideas and paranoias and ways of thinking again and again.

I’m very interested in this question of return. Return to history, to sources, to moments, to narratives. Weirdly enough, I think whenever one revisits a space, something else suggests itself to you. In Handsworth Songs for instance—just to concentrate on one image—we had the arrival of people on the Windrush and it was a major moment in Handsworth Songs because it was about suggesting that something happening in the present might well have a past. By the time I get to that again in the noughties with The Nine Muses it’s a much more bitter-sweet return to that image because of course many of the people in those images have now passed away. Those images are kind of a monument now to their lives, not just a reminder of the past but something of the past that is worth celebrating, remembering. So subtle differences, but yes there is an impulse to return to these moments, with the hope that one takes from it something more illuminating each time.

I also wanted to ask you about the mixing of nature and the human world that can sometimes seem at odds—perhaps not at odds, but they’re often a misfit with one another. There is so much negative human behaviour that is seen in the work, do you think it goes against our nature or is it actually very aligned with it? Is everything that you’re showing natural, animal behaviour or is it something different with us?

I think it’s important for me at the moment to relocate some of our power and actions and impulses in a broader setting. That broader setting paradoxically then starts to be more inclusive. I’m very keen now to build worlds and narratives in which the human and non-human coexist a bit more. Where the ‘natural’ can appear to be both something that we are creating and engineering, and something that is working on us. What I know for a fact is that I don’t want to have the ‘natural’ world as a background, as a backdrop to some sort of ‘human drama’. It’s too myopic, it’s too innocent and it’s not the world I live in anymore. We’ve already changed the so-called natural beyond words and we’re about to fundamentally in the next decade unless things change. So the idea of it just as a backdrop is part of the problem, it’s why we have had some of these ecological disasters in the first place. So I’m definitely trying to find ways of not working or thinking in those terms.

So it’s more of an integration…

Yes, an integration, and a way of trying to get elements to talk to each other. For instance, when you see these polar expeditions in the 1900s and a guy just goes around shooting polar bears for fun. Of course that cavalier disregard for life was to play a very large part in European lives a decade from then—shooting with impunity. The migrations of events and activities that at one stage seemed to be just for polar bears, or just for whales weirdly becomes stuff for human beings. So it’s not worth trying to think exclusively of either the human or non-human, natural or cultural, in self-contained boxes any more. Not for me anyway.

Do you think we will circle back to a more caring and integrative relationship with ‘the natural world’. Perhaps it gets pushed to a point and then comes back around again?

Definitely. I think it has always coexisted with the slightly more indifferent cultures. It’s there, it’s still coexisting, it’s just trying to ensure that we tip that balance even more. Our complicity, and sometimes our unwitting complicity, is destructive. I mean I have sympathy for the view that you hear very often, that we didn’t know. I’m a profound optimist and I believe that if people are given the chance and the resources and the reasons we will do the right thing. I believe that, I have to believe that. The alternative is just too horrifying to contemplate.

‘Artes Mundi 7’ is showing at Chapter and National Museum Cardiff until 26 February 2017.

John Akomfrah, Artist Portrait

John Akomfrah, Handsworth Songs, (Still) 1986, courtesy the artist and Smoking Dogs Films, London

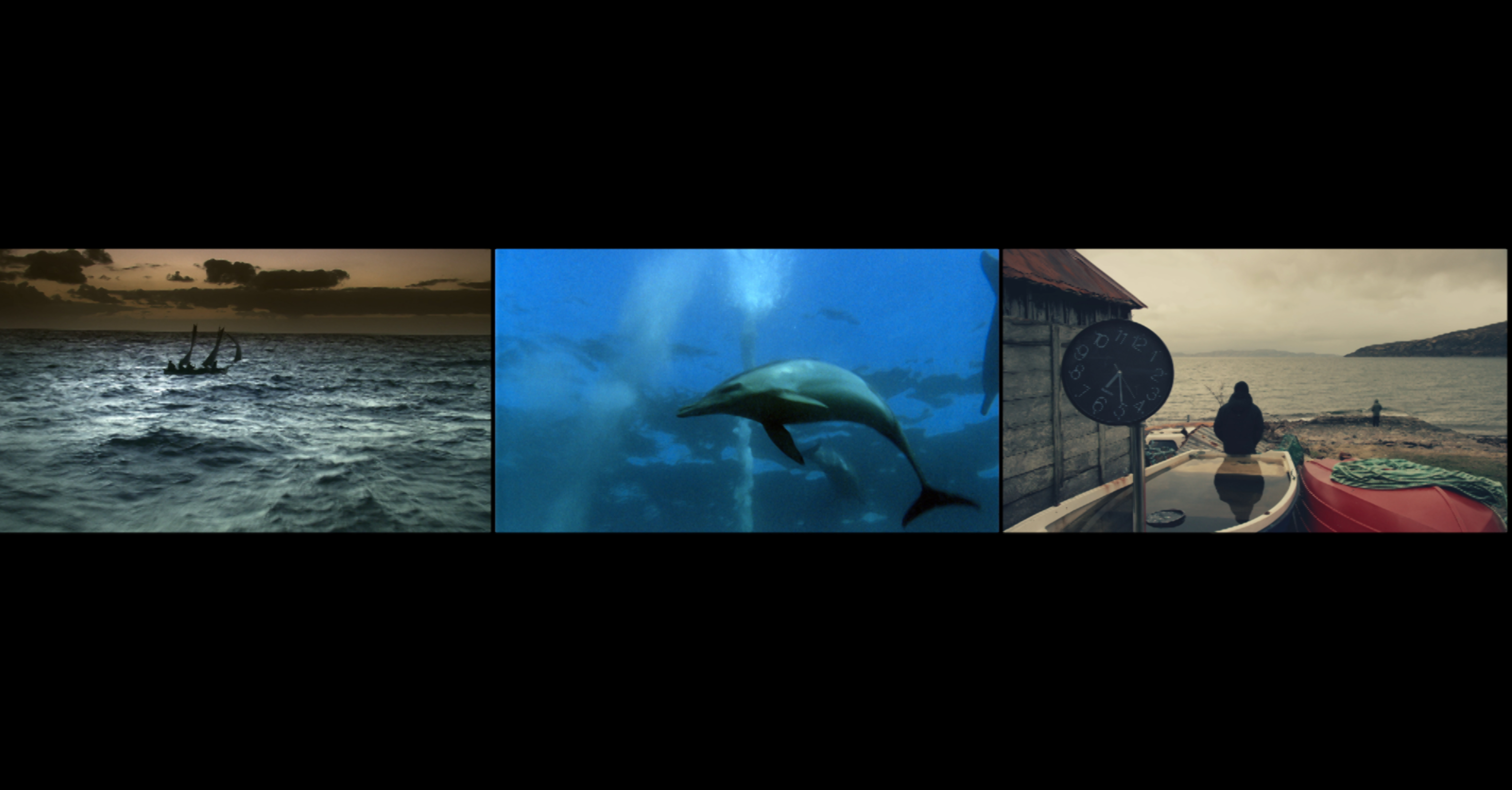

Vertigo Sea, 2015 © Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Lisson Gallery.