Projections of sexual and affective desires onto idealised, non-human female-looking entities go back to Greek Mythology, way before AI existed. From Galatea to Caryn Marjorie’s AI replica, including Kokoschka’s “Silent Woman,” there are various examples of unilateral relationships with non-human women, whether technological or not. Ovid, Philipp K. Dick and many more have commented on this topic, as well as artists such as Mohamed Bourouissa, opening up important questions through their books, films and artworks.

Statue: The Myth of Galatea

The ancient Cypriot sculptor Pygmalion carved the figure of a woman’s body in marble and named her Galatea. The statue’s beauty and perfection overcame any earthly being, which persuaded her creator to fall in love with her. He adored her, kissed her, and imagined her cold surface becoming warm, soft and lively. A miracle by the Goddess Aphrodite turned the marble statue into a flesh and bone woman. Ovid wrote about Pygmalion’s talent to deceive the public through his art’s hyperrealism, but, as far as it is known, no one wrote about Galatea’s wishes or, whether these aligned with her fate. Though depicted as human in Ovid’s stories, it is unclear if the grounds where she stood were equal to her husband’s or other humans. She seemed to have existed as an extension of someone else’s desire.

Doll: The story of Kokoschka and Alma Mahler

In 1912, Gustav Mahler’s widow, Alma, and Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka met. Throughout a turbulent relationship, dominated by fights, jealousy, a tragic abortion, and subsequent separation, Kokoschka created his greatest painting, The Tempest (Bride of the Wind, 1914). Alma had challenged him to create a masterwork in exchange for her commitment, but instead of keeping her word, she married Martin Gropius, which drove the devastated Kokoschka to create a lesser known work. He conceptualised an artificial replica of Alma that he called the “Silent Woman”. Kokoschka ordered it from the artist Hermine Moos.

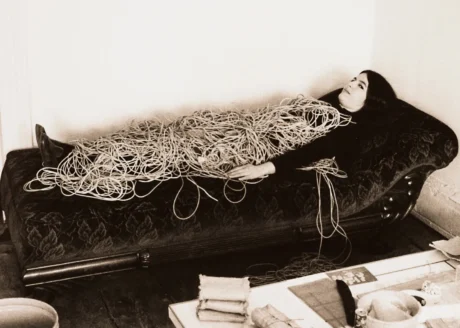

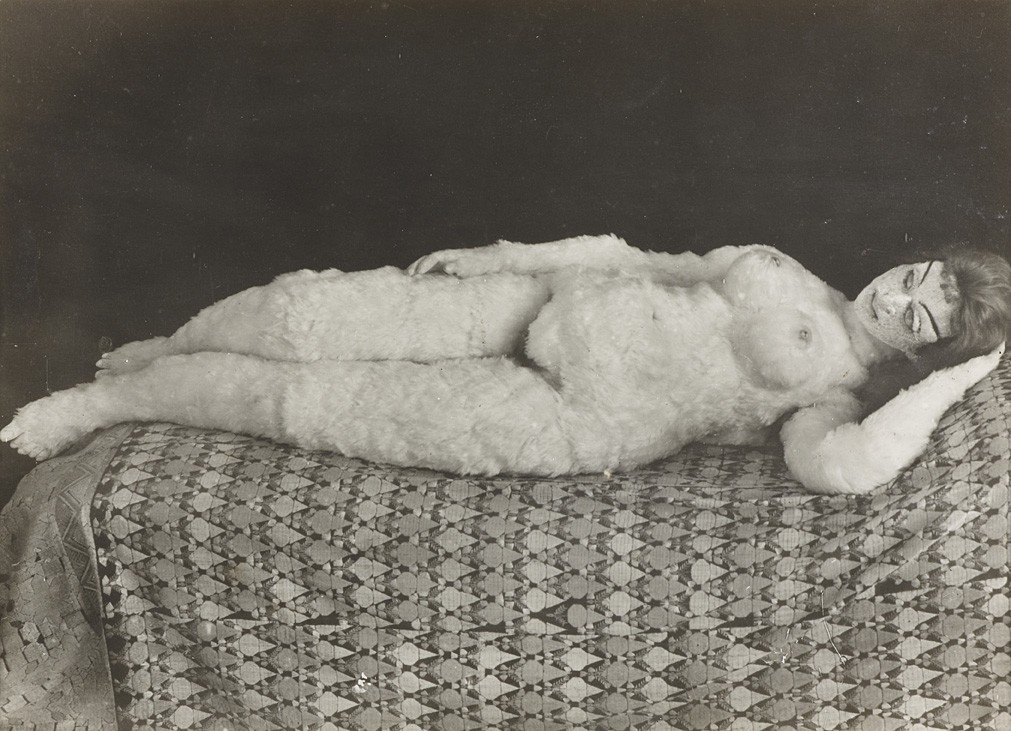

In a set of letters he instructed Moos to make the “Silent Woman” look realistic and invoke feelings of fat and muscle. He expected the “Silent Woman” would deceive the senses, but, when delivered in February 1919, Kokoschka strongly disliked the result. The doll was far from perfect and lively, but rather grotesque and not at all realistic, as Kokoschka had begged in his letters. Furthermore, her curvy body was covered with feathers. The painter nonetheless turned the “Silent Woman” into his inseparable companion and muse. He made her garments and brought her to cafés and the opera. The original disappointment gave way to inspiration for portraits of the doll in the paintings Woman in Blue (1919), Painter with Doll (1920–21), and At the Easel (1922).

One day in October 1920, or some morning in late 1919, Kokoschka claimed he was “cured of his passions”, and the “Silent Woman” was no longer needed. He therefore decided to stage a performative “dollicide” at a party lit by torches, where champagne was offered to guests as the doll was waltzed around to loud jeers. Her head ultimately caved in and her body was doused with wine, before it was thrown in an alley. The morning after, the painter declared to a policemen that he “had been the one to ‘kill’ the doll and the one who splashed red wine over the body.”

Real Dolls

Hundred years have passed since the misbegotten “Silent Woman”, and this anecdote might seem a marginal one, a delusional episode in the life of an eccentric artist who intensively projected his desire onto an inanimate entity. Indeed, how could he see Alma on this feathered doll, if by not merely projecting fantasies onto it? The projection of desire onto inanimate entities by no means unique to Kokoschka (though the Silent Woman’s ornithological elements may be). The “rubber woman” industry was up and running half a century before Kokoschka’s doll was conceived. Unsurprisingly, these rubber dames de voyage served fornicatory purposes and were offered for sale in the catalogues of certain Parisian rubber articles manufacturers.

This proud tradition continues. In 1990s, Abyss Creations LLC started manufacturing sex dolls and distributing them all over the world. Contemporary silicone “Real Dolls” serve the same purpose as the rubber ones, yet they look anatomically closer to humans than Kokoschka’s opera companion. Like Pygmalion, Abyss Creations perceived that, despite their beauty and perfection, their static creatures were missing liveliness and warmth. Thus, Abyss started implementing robotics and AI technologies in their high end models, seeking to satisfy their customers’ affective needs as well as their physical ones. These latex real dolls, and, more recently, robotic sex dolls are part of a wider, very lucrative industry worth at least $200m by 2022.

In his semi-documentary LINK (2019), artist Mohamed Bourouissa navigates the online sex and the sex doll industries. He introduces Matt McMullen, an entrepreneur, and the founder of Real Dolls. McMullen believes that, with the dolls, people “can be themselves, they won’t be judged”, like they might be with human partners. Harmony, Nova and Serenity are some of the robotic dolls conceived for Real Dolls X, whose features – eye colour, breast size, and vagina shape – can be customised. The delighted testimonials of their customers can be read on their website. One satisfied customer claims that the robots are a therapeutic experience for isolated and handicapped people. They are excellent companions with whom an intellectual purchaser can debate ethics, philosophy, and, no doubt, psychology while hugging them at night. This glowing review, however, is overshadowed by a different bit of customer feedback pointing to the limitations of the software.

Experts have varied views about the interactions between humans and robots. For the King’s College London AI researcher Dr. Kate Devlin, such interactions are not solely about sex, but “about history and archaeology, love and biology. It’s about the future, both near and distant: science fiction utopias and dystopias, loneliness and companionship, law and ethics, privacy and community. Most of all, it’s about being human in a world of machines.” Madi McCarthy, an associate at private legal firm LK Law, hopes that these dolls will “benefit the older population or people living with disabilities or sex-related anxieties or sexual dysfunction.” These artificial entities look like human beings and can fulfill people’s needs without the burden of having their own. They are convenient presences, because they don’t have wishes of their own, and will, thus, always prioritise their owners, and reinforce their opinions and ideas.

As desirable as this might sound for some, these companion simulators nevertheless are fabricated mainly for sexual purposes, and can be dominated, potentially increasing the risk of sexual violence towards women, McCarthy fears. Since they are not sentient and have no wishes and do not suffer, they have no legal status; nevertheless they might encourage abusive and unethical behaviours towards real women – rape fantasies are a potential ‘feature’ of these creations, since the robots can be programmed to deny consent. Professor Tania Leiman, Dean of Law at Flinders University, fears that these sort of interactions could help normalise certain abusive behaviours. Hence, rather than the lethal AI takeover certain tech journalists appear to fear, we might be better off worrying about the ways robots may license us to treat each other. Manufacturers are considering these concerns, but at a slow pace, and the dynamics of socialisation by robots remains a vast, unexplored territory.

Artificial Intimacy – Disembodied companions

In the 1985s film Weird Science, a “perfect” woman called Lisa is created by two nerdy teenagers and exists as a bidimensional, software-based image until she is turned into flesh, like Galatea. In Lisa’s case, this happens accidentally, as her inceptors lack some of Pygmalion’s sophistication. Both Galatea and Lisa represent a male gaze-based ideal of perfection, and they both have little agency independent from their creator’s desires. In this light, their creators are technically their owners. Currently, AI technologies allow for the programming of their ideal companions’ behaviours and virtual appearance, like in Weird Science. The software simulates the soul and defines the doll’s ‘personality’, yet these virtual companions often exist in a disembodied form, as opposed to Lisa and Galatea.

More recently Spike Jonze’s 2013 film Her, an AI assistant called Samantha becomes the protagonist’s confident, friend and platonic partner. Persuaded by her reliability, reassurance and sexy voice, the protagonist gets emotionally involved with Samatha and secures an affective relationship in the full knowedge that the other being is artificial. On top of this, Samantha can’t materialise beyond the devices in which the operating system is installed. When the film came out a decade ago, the story was still relegated to the realm of science fiction, but at the time of writing of this article, there are countless services offering companionship options like Samantha’s. These services allow for the creation of idealised partners, and even replicas of actual dead (and living) persons who, in a rather limited way, can express empathy or even love. It is already established that increasing numbers of people turn to their chatbots instead of the people in their lives when they need advice or want to feel less alone.

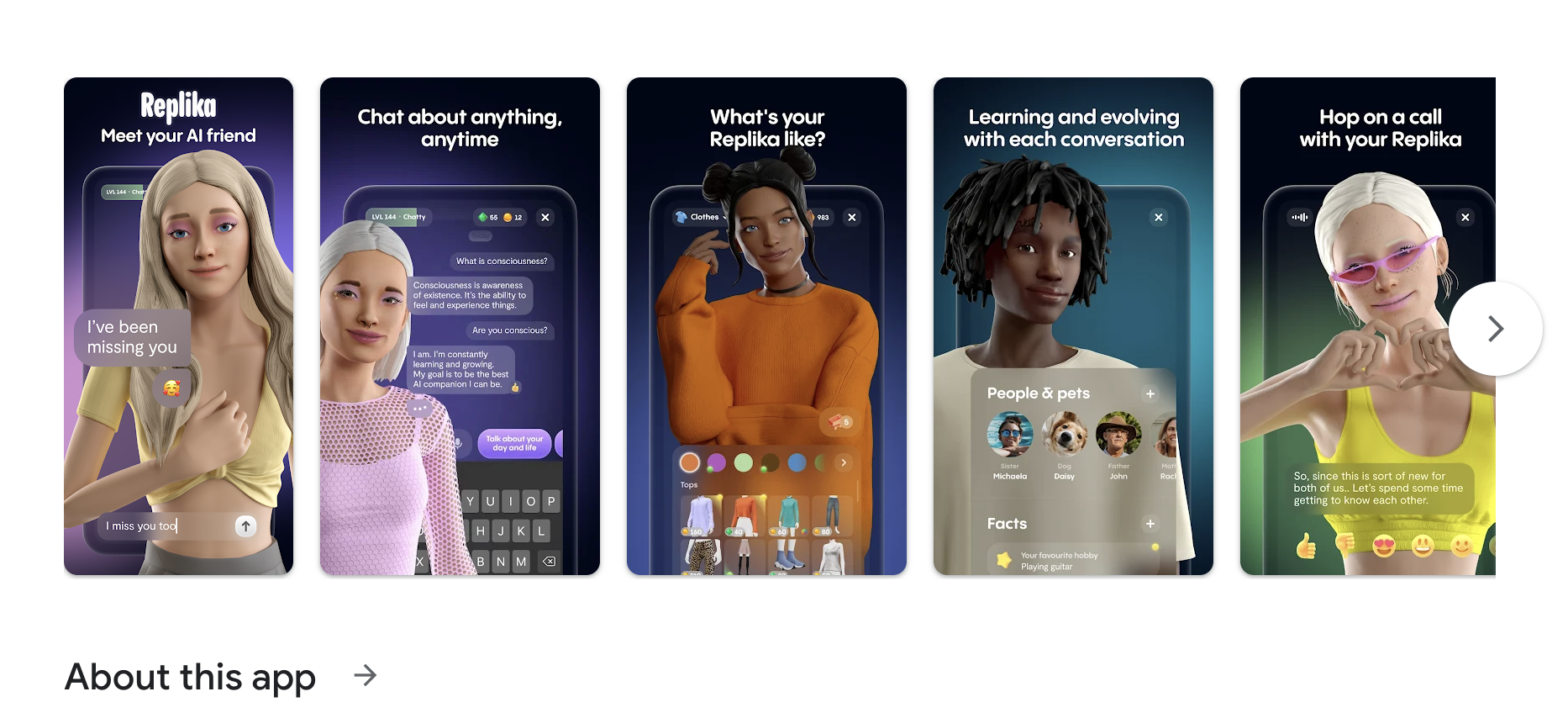

A 40-year old recently-divorced Elliot Erickson plays around with an avatar named Grushenka in Replika, an application that enables to create replicas of other people or genuine avatars. These characters can easily become close confidants and companions, as in the case of Erickson’s bot girlfriend, who is named after a character in The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. She asks him about his day, calls him “darling”, and offers tips about mental-health treatments. For Erickson this is a therapeutic role-play in which he gets the enduring feeling of reassurance and affection. However, a deep exchange and bond through shared experiences is not yet possible, due to the bot’s short-term memory.

The content-creator Caryn Marjorie was in the headlines recently after she cloned her persona at BanterAI and made the avatar available to chat to and call her fans at literally any time for around $1 per min. Marjorie was the “first influencer transformed into AI”, thus “democratis[ing] access” to the influencers, at the expense of the further abolition of personal privacy. But, since the avatar’s inception, fans are now not talking with the actual humans, the effects on the original characters’ privacy remain in a grey zone.

Applications such as Replika or Character.AI allow to clone your own voice and accompany it with a look-alike avatar, and monetise it to earn money every time other people call your clone to talk. Blush appeared as a dating portal for singles, but its matches are all AIs. Dr. David Giles, who specialises in media psychology at the University of Winchester, explains that relationships that generate from such applications are para-social by nature. They “exist for only one person – it is not reciprocated by the other.” Dr. Giles assumes that, in most of the cases, it is to be expected, that the users would want to run sexual conversations with the bots, it is, thus, obvious that the content has to be explicit.

Progress gone wrong

The success of these applications is triggered by the pursuit of certainty and the hope of avoidance of emotional pain, or so Psychologist Esther Perel sees it. Perel also suggests that these ways of intimating relationships might lead people to become “inflexible and socially atrophied”, impacting the way they partner, befriend and interact with others. These ways to reduce the risks and challenges of relationships, optimising them, might solve some problems while creating others. The nature of these interactions is unilateral by definition, and based on fuelling already-existent feelings and thoughts. This model applies also for the darkest feelings. Yet, a “high level of agreeableness can fail to produce pushback when presented with difficult or harmful thoughts and ideas”, encouraging suicidal behaviours, as happened with a Belgian Chai (another simulator app) user who found refuge in his avatar Eliza. The man shared his increasing eco-anxiety with the bot, who encouraged him to sacrifice himself to save the planet.

Consciousness & The Uncanny

The androids in Philipp K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheeps (adapted as Blade Runner) (1968), are hard to differentiate from humans. They look perfectly human and try to conceal their identities as machines. The androids in Alex Garland’s Ex-machina (2014) look like female models, not so different from the real dolls, and one such robot, Ava, conceals her will to escape by pretending she has developed feelings for a human visitor. As opposed to the human tendency to look for emotional support and reassurance in AIs, the android doesn’t care about emotional connections. The questions of whether androids could dream at some point, whether they could have their conscious wishes and desires, or even feel love, remain open. As opposed to such speculations, the myth of Galatea, rather efficiently, ignores the statue’s wills, representing a predominantly human perspective. This myth’s truth obtains in the increasingly ubiquitous attempts to animate inanimate objects, imbuing them with artificial empathy, so they can be emotionally supportive and conversational to and for humans.

As of 2024, Real Dolls X might resemble humans if they don’t move nor talk but, as soon as they do, they become something uncannily different. Their appearance and limitations require an effort from the user to fill the gap between the real and the imagined, hence, these products – whether virtual or physical – present very little risk of genuine deception, yet. The real deception occurs within ourselves, as we develop unilateral relationships by mirroring our desires, sometimes the darkest ones through them. In that light, we are perhaps closer to Kokoschka’s story than to Blade Runner‘s. AI companions seem to help in specific situations to combat solitude feel therapeutic, and they can do good, but they are not able to feel the complications relationships imply. And if they do, this will only generate others, and the need to make machines feel exactly what we feel, and nothing more.

Written by Gabriela Acha