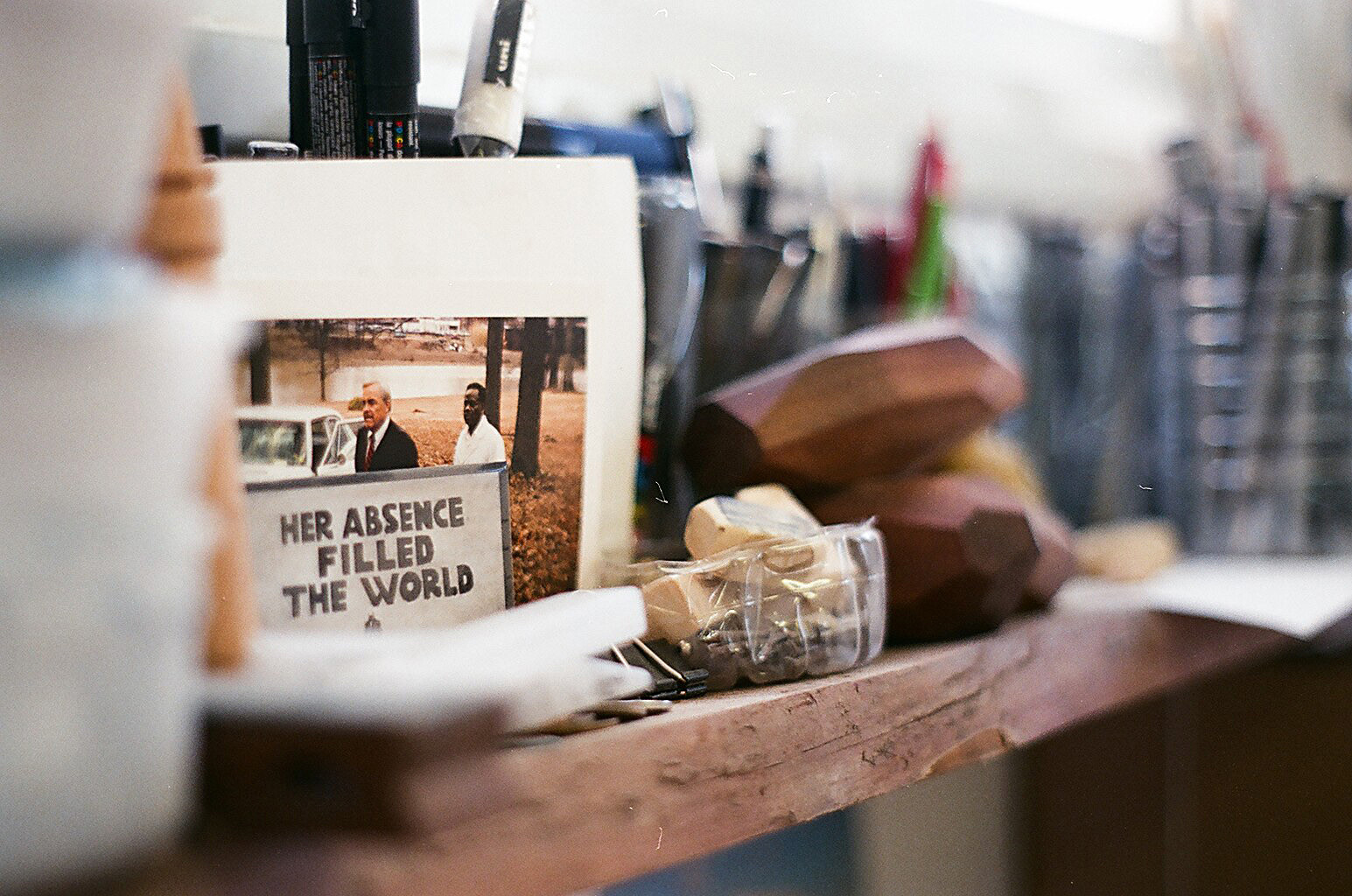

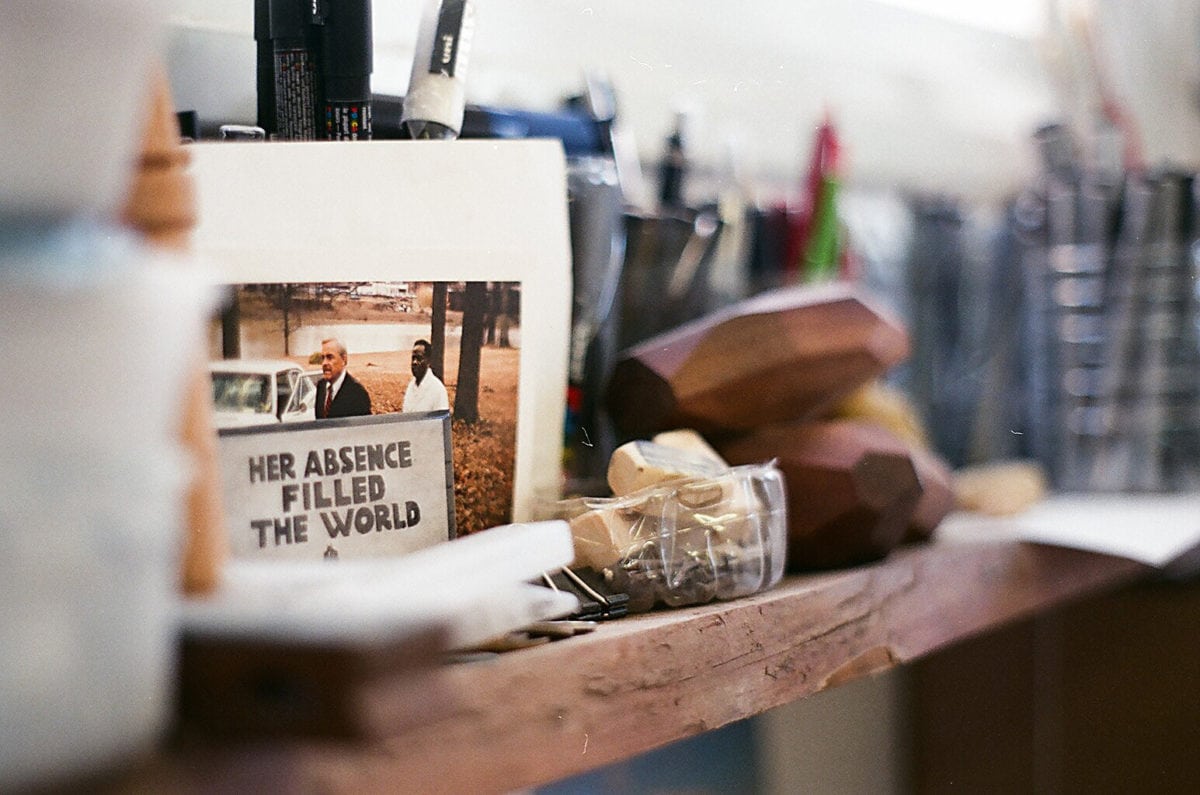

In his early twenties, Addam Yekutieli was a rising star who went by the pseudonym of Know Hope—in many ways he took up the mantle in the spirit of the Beautiful Losers, a group of American DIY artists working in the 1990s who emerged from subculture scenes and mixed graphic styles from skateboarding and punk with poetry and lyricism. Yekutieli’s works also intertwine those strands: words are important, whether it’s in the poetry and aphorisms he writes and has tattooed on skin in his distinctive visceral scrawl, or personal letters exchanged with strangers. Fragility is also characteristic: sculptures are made from materials that look vulnerable—paper, plaster that looks like it could shatter, glass vitrines, twining, rope and birds are all regular motifs in his fine-lined drawings and delicate paintings. Yekutieli’s persistent concern, strung up on a gallery wall or writ large in the street, is always the same: how to find unity in a fragmented world. The starting point is often his own mixed heritage (Japan, the US, Israel) and his experiences living in a society where borders, lines and divisions are part of everyday existence. I visited his studio in Tel Aviv.

In his early twenties, Addam Yekutieli was a rising star who went by the pseudonym of Know Hope—in many ways he took up the mantle in the spirit of the Beautiful Losers, a group of American DIY artists working in the 1990s who emerged from subculture scenes and mixed graphic styles from skateboarding and punk with poetry and lyricism. Yekutieli’s works also intertwine those strands: words are important, whether it’s in the poetry and aphorisms he writes and has tattooed on skin in his distinctive visceral scrawl, or personal letters exchanged with strangers. Fragility is also characteristic: sculptures are made from materials that look vulnerable—paper, plaster that looks like it could shatter, glass vitrines, twining, rope and birds are all regular motifs in his fine-lined drawings and delicate paintings. Yekutieli’s persistent concern, strung up on a gallery wall or writ large in the street, is always the same: how to find unity in a fragmented world. The starting point is often his own mixed heritage (Japan, the US, Israel) and his experiences living in a society where borders, lines and divisions are part of everyday existence. I visited his studio in Tel Aviv.

Perhaps for those that don’t know your work and your background, we can start with your early career, when you were known as Know Hope?

Perhaps for those that don’t know your work and your background, we can start with your early career, when you were known as Know Hope?

I started creating work in public spaces around 2005 and during that period there was a lot of experimentation—mainly trying to understand the various methods of communication that are possible in such a realm. Shortly after starting this process I started writing “Know Hope”, which I never intended on becoming my artist name. With time I developed a deeper understanding of the philosophical meaning and layers within that phrase and developed an iconography, a visual language through which I could conduct this dialogue—one that allows an ongoing observation of our surroundings and the collective reality that we are all part of. My work since then has revolved around various forms of public intervention, whether they be installations, wall paintings or text work.

You’ve been aligned with street art in the past, showing at galleries like Laz Inc and Known Gallery in LA. I’ve always seen your work as having more in common with public conceptual art. I know artists always like to evade definitions, but do they help people access and understand the work better, do you think?

It’s always been a priority of mine that my work be inclusive and engaging, as the role of the “viewer” has always played a large part in my creative process. I can understand how definitions or titles can help people understand the work by associating it with a certain genre, but I feel that doing this is reductive in most cases. I feel that this is problematic, as it often brings with it certain preconceived agendas and motivations that are attached to the work itself that many times do not align with my choice of working in public spaces. A lot of my work does take place there, and my choice to do so stems from at times preferring specific contexts within larger environments for the pieces, in order to allow them to become part of everyday life and be interpreted as part of the overall dynamics. I always saw myself and an artist to whom context is important, and the street many times is that context, though not exclusively.

How long have you and your team been in your current studio here in Tel Aviv and what do you like about it—and the area?

I’ve been in this studio for about three years, and the crew varies between two to four other people, depending on what we’re working on. I love working in this studio primarily because of the large amount of natural daylight, something that was sorely missed in my previous studio.

My studio is right on what I call one of the “seamlines” of Tel Aviv that is at a junction that connects the centre, east and south sides of the city. I call it a seamline because the contrast between all the areas is so harsh, but they are in such close proximity one to another. The bourgeois neighbouring city centre and the high-rise office workers who mix with the street people on the other side of the road during their lunch break. You walk a little further and you’re in another Tel Aviv. I think this creates a really interesting juxtaposition.

In your more recent work—projects like Truth and Method, Vicariously Speaking, A Collective Heartbreak—you have been using a collaborative approach, inviting the public to contribute and share stories, text, images… What is it that you like about working like this?

My work has always been based on observations, real-life situations that surround me, that I attempt to translate into a more universal representation through my imagery. At a certain point I felt that it might be interesting to work with these people, as opposed to observing them, and allowing them to take an active part in these processes.

Due to working under a pseudonym for so many years, a certain distance was formed between myself and the viewers and I wanted to create more of an unmediated experience, which is also why I started working under my real name.

The human condition has always been the centre of my work and conducting a process like this creates a situation that I am not commenting on, but more suggesting from within.

I think one of my favourite works of yours to date was your very recent mural, 246 Sides to a Story. Not only in the context of all the problems in Jerusalem, but it really resonates with the way we’re living today. It’s such a poignant work that dovetails so many issues so beautifully and concisely for me. Can you explain more about the mural?

I’ve always been interested in attempting to address political situations from an emotional or even sentimental standpoint. The building is located near the Green Line and the facade from all sides is covered with bullet holes, primarily from the Six Day War. I wanted to approach it as a collective historical experience, but give each bullet a narrative, a personal story. This led to assigning a short text to each numbered bullet hole, creating an index of sorts. I wanted to attempt to dissect the political reality that has formed since and see it as a collective psychology, composed of these small moments of personal perspective that will hopefully allow a different understanding of the current situation in this region.

With this piece, the concept was developed around the wall/building itself. Once I heard the story and learned more about the location of the building I felt that it wouldn’t be right to paint a piece that covered the surface. Instead I wanted to find a way to emphasize the history of the building by bringing the bullet holes to the forefront.

It was a very surreal experience, as the days we were working on it coincided with the massive and violent protests at the Gaza border, the relocation of the American embassy and Israel’s celebrations after winning the Eurovision created surreal energy of intensified desperation combined with grotesque patriotism. These clashes created an interesting experience to work in, while reflecting on the building, which was almost like an “artefact”, or symbol of a historical milestone.

Not long ago I sent you a photo of the scar on my elbow for a project you’re working on at the moment Our Skin, Our Land. What’s going on with that now?

For the past six months I’ve been working on this project in which I’m building an archive of scars of people living in the Middle East as part of what I see as an ongoing research on the correlation between scars and territorial borders. I take photos of the scars and collect stories written by the participants about various facets of their relationships with their scars—how they were created and other anecdotes and reflections on them.

The photos will later be used to form a “reimagined” map of this region, by finding borders (past and present) that resemble that shapes of these linear scars. In this project I attempt to draw parallels between the notions of belonging and frontiers, mending and reclamation, trauma and nostalgia.

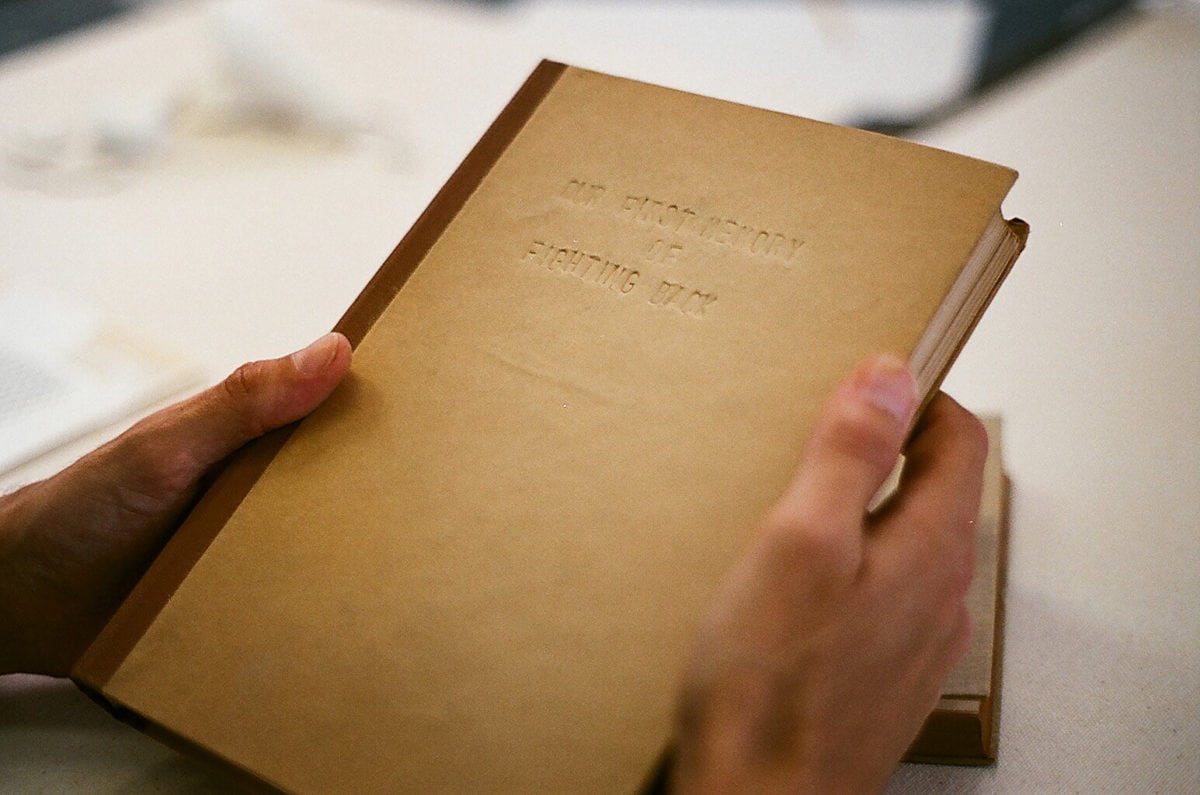

Some of your recent works, such as It Was Overwhelming, suggest you’re obsessed with finding order… What do you like about indexing objects?

One of my main intentions with these works is to show the multiplicities of experiences that compose a situation or object that is usually seen as having objective meaning. For example, there’s a series in which I undo mate wire fences, separate each wire by slowly unravelling the fence, separating it into individual wires.

A fence is one unit composed of separate intertwined wires, though they are not actually fixed to each other. I later number each wire and assign them with a sentence or phrase in an attempt to personify the fence, by setting them apart and portraying each one as an individual experience. Essentially, it’s an attempt to personify the objects that I index and focus on the emotional situation that composes larger and seemingly more dense and complicated situations.

Thinking about it, your work is very tidy, very quiet—you seem quite strict when it comes to how its presented, hues and tones you use, the way you arrange the different elements of your work (drawing, painting, writing, sculpture). Perhaps I’m analysing you as a person through your work too much—but I know you have a deep political conscience doing what you do.

I attempt to bypass the normal traps of the rhetoric revolving around these issues, by allowing access points that are familiar and making connections between our individual feelings and our understanding of the circumstances we live in.

I mean this in the sense that people might feel wary of or not feel knowledgeable enough to speak about a subject like the Occupation, but they could easily speak about their personal experience of heartbreak. I’m interested in this paradigm shift, these meeting points of understanding that you can take insights from a certain area of your life and apply them to others.

I imagine with your work you might also feel frustrated sometimes about the outcome of having exhibitions in white cubes and having works that are sold? How do you feel about all that? How do you balance it? What would a dream project be like for you?

While the merging or combination between the commercial and creative facets of art making is a very sensitive one, I find it interesting knowing that my work receives an extension due to that fact that it’s commercially sold and later on put in different contexts and lived with, in a way.

Throughout these exhibitions, there are always projects that continue independently and regardless of them. For me, it’s really about finding the right environment for my works, with respect to the motivation for making them and content they deal with and knowing to differentiate whether it feels organic or not.