A muse, in the most basic sense, is a person who serves as an inspiration to an artist. The word itself dates back to Greek mythology, with Zeus’ daughters forming the nine Muses who presided over the arts and science. This ethereal quality to the term adds a weight and sense of grandiosity, something that Katie McCabe, author of the recently published More Than a Muse: Creative Partnerships That Sold Talented Women Short, believes can warp our idea of what a muse can be.

“The idea of ‘invoking the muse’ suggests a spirit, not a person,” she says. “A muse supposedly provides a source of inspiration for an artist, but that ‘source’ can come in so many different forms, whether that’s posing as an artist’s model or just offering advice and support through the creative process.”

McCabe’s book, in part, aims to unpack the complex relationships between female muses and their more successful male counterparts, and also explore how the upheld notion of a muse has left many women overshadowed, anonymous or underestimated in their work. Looking at the artistic partnerships of writers, musicians, filmmakers and artists, and celebrating the women who were a part of them, McCabe hopes to help us understand what being a muse actually involved.

“The image of a beautiful waif as a source of creative revelation to a brooding older, artist has been perpetuated in countless films”

It’s in the art world especially that tales of artists and muses have been able to flourish and become romanticized over the centuries. The image of a young, beautiful waif as a source of creative revelation to a brooding, often older, artist has been perpetuated in countless films and TV programmes, and McCabe thinks this is because of our conflation of “model” with “muse”.

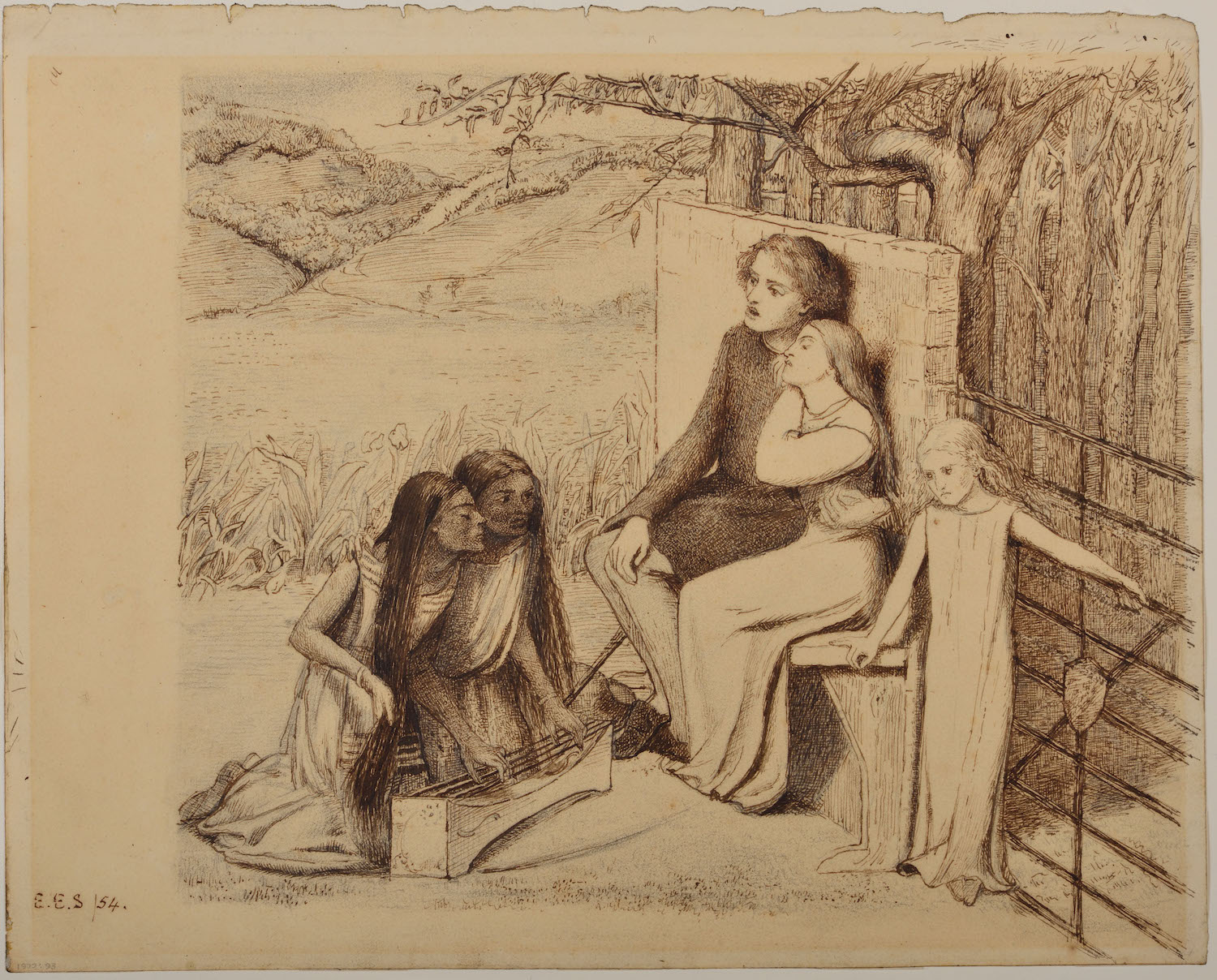

“When someone is sitting for an artist for long periods of time, it can become an intense artistic collaboration. There’s just so much ‘looking’ going on,” she explains. “The artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood really leaned into the romanticization of the model—they shaped their work around it. And for the women who posed for them, it served as a way to ingratiate themselves further into the art world at a time when they were unable to access formal training at places like The Royal Academy of Arts, which didn’t admit women until 1860.”

McCabe cites Elizabeth Siddal as a classic example of this. She was an artist and poet in her own right, but has more often been described as the “tragic muse”, and it’s meant her life has become intertwined with the Pre Raphaelites’ artistic portrayals of her. Even today, there have only been two solo exhibitions of Siddal’s work: one in 1991 at the Ruskin Gallery, Sheffield and a second in 2018, titled Beyond Ophelia, at Wightwick Manor. The show featured twelve of Siddal’s works and examined her career, style and the prejudice she faced as both a female artist and a muse.

One commonality McCabe sees between muses of the past is how often the woman would start out with a thriving, or at least promising, artistic career of her own, which would eventually become sidelined as the man’s fame grew. “She would be recast in the role of muse, wife or girlfriend, blurring the success and autonomy that had come before,” says McCabe. “For instance, when Josephine Nivison met Edward Hopper, she was featured in multiple group shows in New York, exhibiting alongside Man Ray, Picasso and Georgia O’Keeffe, while he was mostly working as a commercial illustrator. It was Nivison that got him a spot in the Brooklyn Museum exhibition where Hopper sold The Mansard Roof, an event which really kicked off his career.”

- Josephine Verstille (Nivison) Hopper, Untitled (Portrait of a Woman with Brown Hair) and Untitled (Landscape). Courtesy of PAAM, Gift of Laurence C. and J. Anton Schiffenhaus in memory of Mary Schiffenhaus, and two anonymous donors, 2016 and Gift of Alfred T. Morris Jr., 2000

On top of this, Nivison (who did eventually become a Hopper) itemized and recorded all of Hopper’s work and spoke to the press on his behalf, while he worked in a big studio in their home. She had just a small space behind the kitchen to create her own work. “The women in those artistic partnerships were so often the organizational force in the relationship, looking after the mundanities of life so the male partner’s work could take precedent,” says McCabe.

This is similar to Dora Maar, with much of her innovative photographic work being completely overshadowed when she met Picasso, who reduced her to a two-dimensional figure in his works. “His work was so closely tied to his relationships that the time Maar spent as his girlfriend became a kind of ‘marker’ in his career,” McCabe explains.

“The women in those artistic partnerships were so often the organizational force in the relationship, looking after the mundanities of life”

“The Tate Modern retrospective last year was a move in the right direction, it showed her surrealism, the fashion portraits, the photomontages, the disturbing street photography,” the author adds. “For decades, we swallowed this image of the Weeping Woman that he served up for us. There had been reappraisals of Maar’s work before it, but sometimes, when the damage is that severe, you need a blockbuster show on that level to restore the balance.”

Part of the reason we’ve maintained this limiting idea that muses are women and artists are men, is because the concept was delivered to us through the male gaze from the beginning. Once regarded as a muse, these women were reduced to that role only, and any effort to go beyond that was often quashed. Many people, not just the artists who called these women their muses, but the gallerists, critics and collectors, felt being a muse should be enough for these women, and to seek their own success was unbecoming.

McCabe sees the life and work of Camille Claudel as a prime example of this happening. “Claudel was involved in the creation of Auguste Rodin’s sculptures when she worked in his studio, there is so much hidden collaboration there. One of her own works, Giganti, has his signature on the neck, bringing up the issue of misattribution,” McCabe notes. “She would spend hours sitting for him, which meant she had less time for her own sculpture. Claudel struggled to get state commissions for her sculptures, such as The Waltz. She was instructed to clothe the nude dancers as they were considered indecent, because it was produced by a woman. It was like she was being punished for her talent.”

Though there has been a lot written about Claudel, the focus is often just on the tragedy around her situation, with an emphasis placed on female pain. “While it’s so important we acknowledge how she was treated, I’d like to see more discussion of her sculptures,” says McCabe. “The opening of the Musee Camille Claudel, in 2017, was a huge step forward.”

“We’re not seeing a dissolution of the ‘muse’, more a reframing of the traditionally held notion of it”

It seems through these big retrospectives and specially dedicated institutions that we’re slowly gaining a better sense of how much sacrifice being a muse actually was. Many muses lacked the space to create, sacrificed time tending to the needs of the artist, and were vastly underestimated as creative beings.

“As director Ceilina Sciamma pointed out, the term muse has been pretty successful in hiding and undermining collaborations in art, and has skewed our view of women artists who also happened to occupy that role,” explains McCabe. “Many ‘muse’ stories have been reappraised, and that is valuable, but for those who produced work of their own, such as Maar, Claudel and Hopper, it is so important that we continue to reappraise that, too, so we can move away from the idea of being ‘overlooked’ and just see them as artists.”

The attitudes surrounding these kinds of artistic partnerships are now outdated––though there is argument to be made that it’s still not all that equal in the art world. We don’t tend to hear of many contemporary artists talking about muses these days, so is the concept truly a thing of the past?

“I don’t think what we’re seeing is a dissolution of the ‘muse’, more a reframing of the traditionally held notion of it,” says McCabe. If we were to redefine the concept of a muse as something more human, as a coming together of ideas between two people instead, perhaps that would help in getting us closer to seeing those involved as artists and creatives in their own right. For McCabe, the notion of an artist’s muse should be simple. “The relationship of muse and artist should be about collaboration and the exchange of power,” she says. “Not the hoarding of it.”

Are you a painter? Whether you’re just getting started or refining your craft, Elephant Kiosk‘s range of high quality and sustainable art supplies is here to keep you creative.