From a young age, Paloma Tendero knew she had a hereditary disease. It was only when her mother lost her life to the illness, however, that Tendero began to realize how serious the condition really was. “The psychological weight of not knowing what is happening in my body and when it might change means I’m never really free—I think my art is often a response to what I’m going through. There are a lot of taboos around talking about illness and it can be isolating sometimes.”

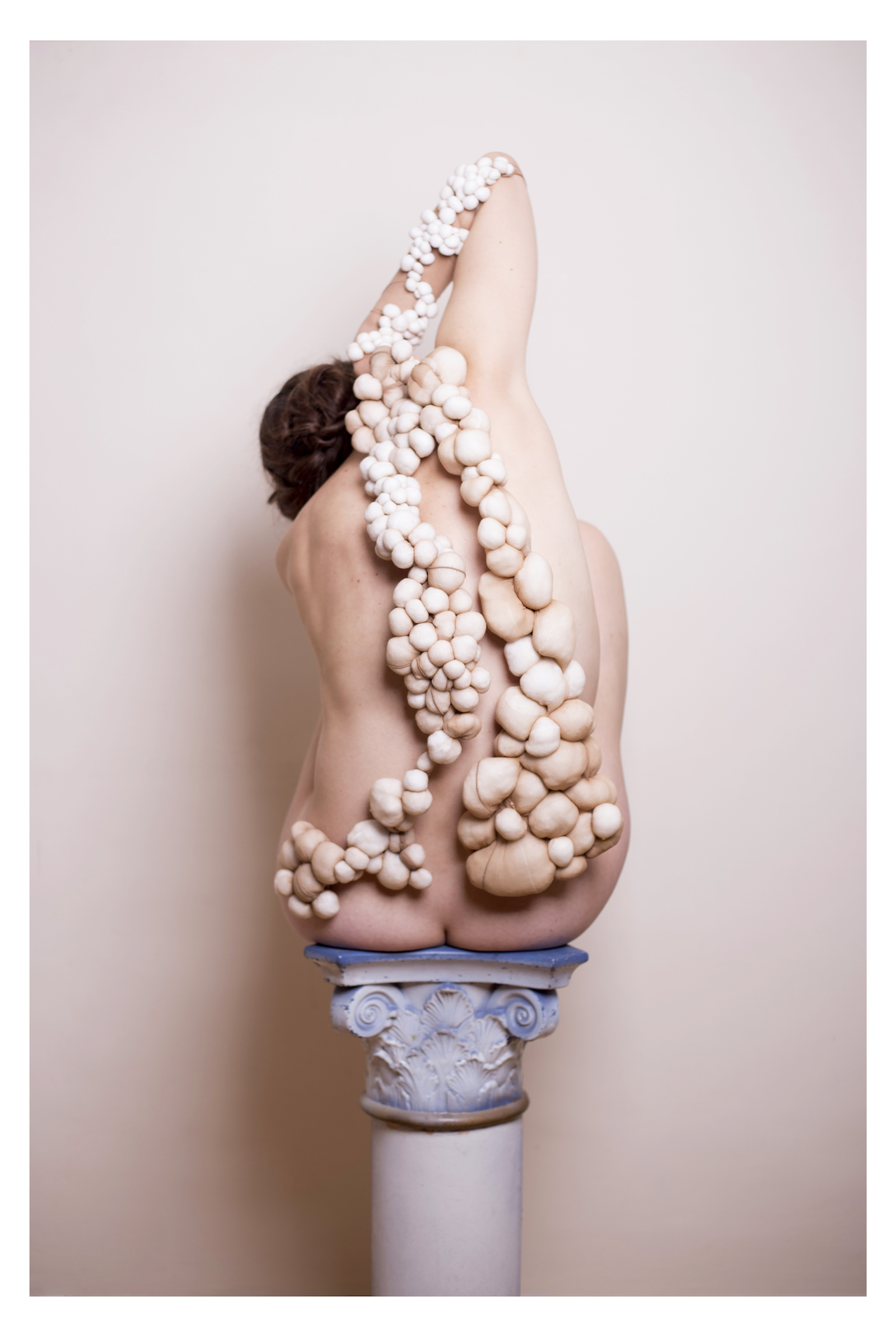

Tendero, who trained in sculpture in Spain and moved to London to do an MA in photography at LCC, makes work that attempts to visualize what is going on inside her body, to make it both controllable, tangible and beautiful. Now resident at the Sarabande Foundation’s East London studios, in her early works she has played with the aesthetics of the disease, reimagining microscopic views of the cells with thread and embroidery wrapped around her naked body.

She has also referenced representations of female figures in Ancient Greek sculpture and mythology, such as the Medusa. “The Medusa is a monster but is also alive, it’s like the illness—it’s horrible and beautiful at the same time.” Illness is typically represented in a negative or fearsome way in visual culture, but Tendero gives us another perspective of illness that’s more ambiguous; feminine, delicate and savage all at once.

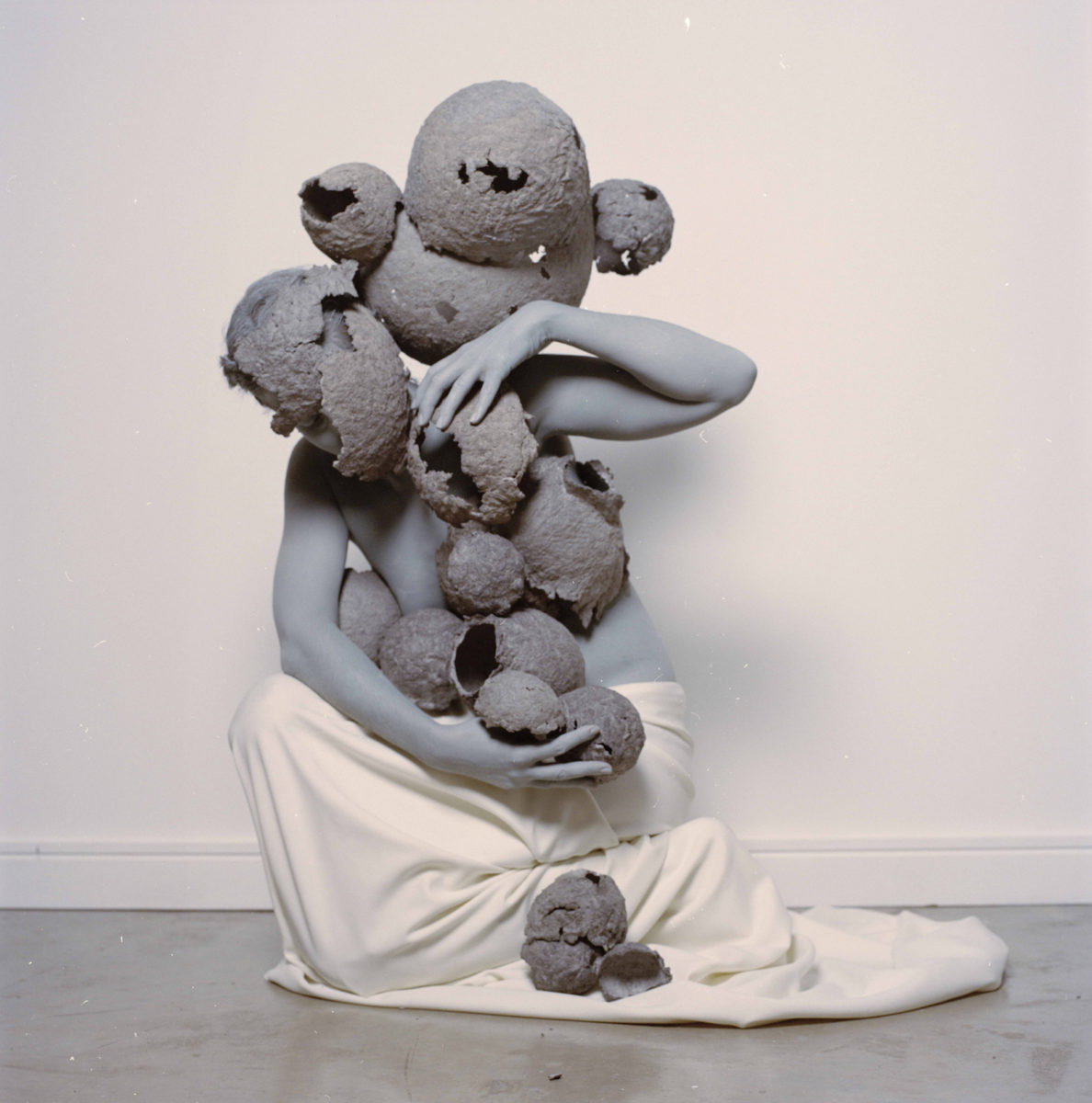

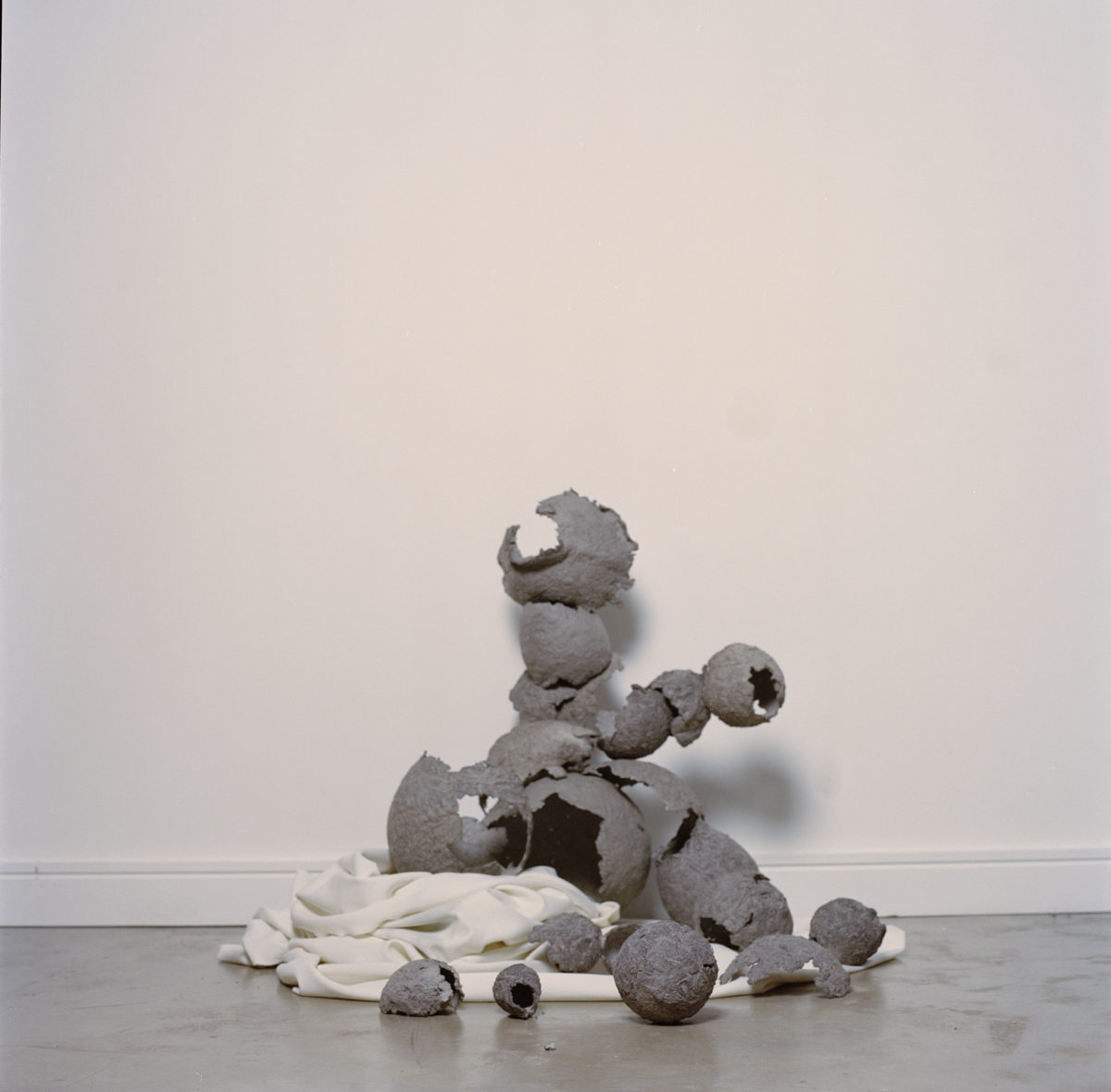

In a recent performative photographic work, Flawed Beauty, she creates representative cyst-like shapes from soft, tactile everyday materials, and wears them. At times they seem to engulf and overwhelm her body, at other times she is able to hold them back. “For me, this series is about acceptance”, Tendero explains. “I sometimes feel I envelop my body with the illness, sometimes I embrace it; sometimes I want to remove it and take it off.” Though her art always relates to this personal struggle with her own body, Tendero touches on a subject that is widely resonant: “Your body is your friend when you’re healthy but it’s your enemy when you’re sick.” Her latest work, On Mutability, also references classical tropes around the female body, specifically dealing with fertility. In a similarly ambiguous gesture, Tendero clutches and releases egg-shaped sculptures, broken and imperfect.

“There are a lot of taboos around talking about illness and it can be isolating sometimes”

“Susan Sontag speaks about this in Illness as a Metaphor, the fact that ‘Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.’ I think this is what I want to explore, not only focusing on what happened to me.” How to live with our own mortality and physical vulnerability? By visualizing the invisible transformations that take place inside the body through images, perhaps we can connect more fully to our experiences.

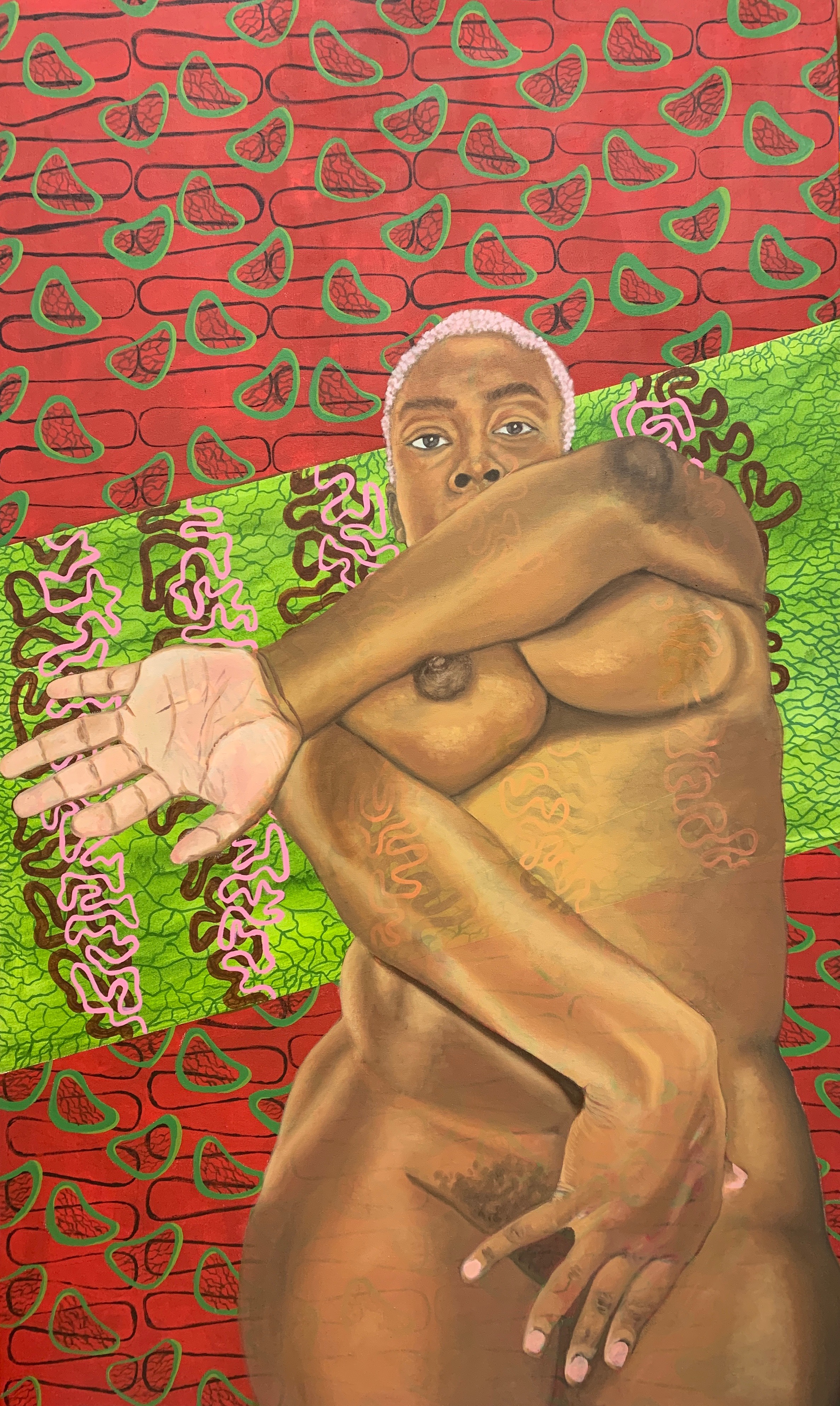

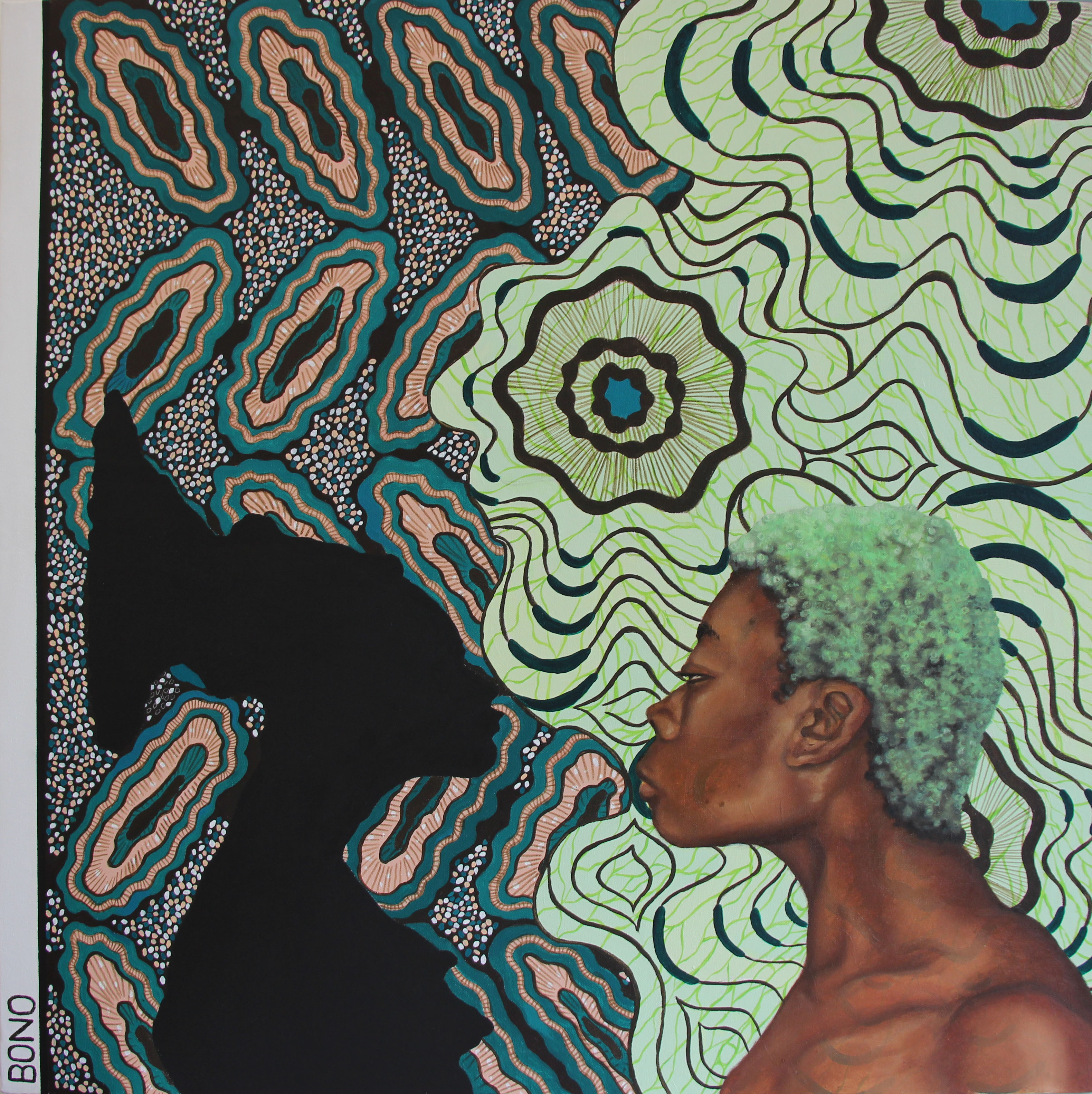

Working across the hall from Tendero at the Sarabande Foundation is the painter Shannon Bono. Stepping inside her studio, stacked with large, lucidly-coloured canvases and pots rammed with paintbrushes, her practice at first seems entirely opposed to Tendero’s, but it turns out they are equally interested in representing female bodily experiences in transgressive ways. Bono portrays women—some of them almost life-scale—majestic and imposing in both their size and gaze.

The portraits, mostly nude, are painted from photographs. They are set against patterned backgrounds that refer to fabrics and textiles symbolic in the countries of her dual heritage, Sierra Leone and Congo, themselves used to wrap the body in different ways. The shape of sickle cells and nerve cells has also been the basis for another painting’s symbolic background; Bono, like Tendero, is interested in what happens inside the body as much as she is concerned with depicting what we see.

“For me, I’ve always been interested in the female form. I was always drawn to the power of the female body, especially the black female body. The body itself is what we use to interact with each other in the world, its how we form our perceptions of each other, so I thought that was the place we should tell our stories. I manipulate the anatomy to tell stories. I might cut my own body open in the painting, slice open the throat or have limbs missing; it acts as a second canvas.”

Veins and connective tissues are also motifs in her works, referencing Byzantine painting, Catholic symbols, as well as African Voodoo and iconography. In one particularly violent painting, Bono mutilates her own body, a reference to atrocities suffered during the blood diamond trade that led to the civil war in Sierra Leone; another refers to the amputations that happened in that Congo during the systematically violent reign of King Leopold II, in which men, women and children were tortured and brutalized when the quota of rubber was not met.

Bono recalls how she has been struck by the way bodies account for history that has an impact on the present, as she visited institutes like the National Gallery. “Portraits tell you your place in society—it’s about representation, seeing these bodies with these gestures and poses, let’s people know our stories as women of colour.” As she read black feminist literature and considered the colonial history of the camera and its gaze on African female bodies, nudity was a problematic issue for Bono at first, but now most of her figures are unclothed, including a self-portrait and a recently completed painting of a close friend, eight months pregnant. “I have to re-tell the stories of these bodies in a different light. I find the body beautiful but I have to remember the stories I’m trying to tell and how the body will impact the viewer. Nudity is important for letting the viewer into that sense of vulnerability.”

Camilla Hanney is also resident at Sarabande, and met Tendero and Bono through their shared interests. Her studio is filled with fragments of ceramics: a cast of cremated crochet hangs on the wall, a pile of grey clay Aran cardigans is stacked against a wall, balanced above our heads is a skeleton clad in hide. “I’m thinking of making a cyanotype of it, or taking it to one of those tanning beds,” Hanney laughs. The works look delicate but the stories of the women they recount are far from it—archival accounts of subversive sexuality, supernatural bodies, female labour, poverty and desire Hanney resurrects and preserves with her hands.

Seventeenth-century treatments for syphilis, that caused hair and teeth to fall out, are referred to in one work she shows me, another work tells the history of the Gut Girls of Deptford hired to work in slaughterhouses because of their nimble fingers. “There’s such a problem with women handling blood and gore, meat and carcasses, it’s considered outrageous, but women did a lot of unsanitary jobs then,” Hanney explains.

“I manipulate the anatomy to tell stories. I might cut my own body open in the painting; it acts as a second canvas”

Veering from tropes associated with the hyper-feminine (lace and long hair) to the strange (hybrid animal forms with female genitalia, oysters holding vaginas) Hanney’s palette of white and waxy hues recalls bones, ash and dust, embedding a sense of history and time materially within her works. White also carries connotations of purity that is demanded of women’s bodies but that often contradicts how we view them. In Hanney’s work too, bodies are dismantled and displaced, and she often juxtaposes sexuality and the perfunctory, seduction and repulsion: a ceramic pillowcase seems to stifle a female torso beneath; in one installation work made up of tiny forms and fragments, tentacles and nipples multiply and fall in cascades. Ceramic has been the perfect medium for Hanney to evolve her explorations of “the body in a more universal way; we all hold these stories. I look a lot at art and religion as starting points in which these very dated and dangerous female ideals were constructed, and also contemplating on femininity itself.”

As Tendero, Bono and Hanney’s work suggests, our persistent, shared idea of femininity is archaic, and hardly follows from the individual histories and lived experiences of women. Pain is, and has always been, a fundamental part of the female body and biology—as much as our ability to endure it. Each of these artists, through their own distinct personal stories and contrasting practices, dismantle bodies to deconstruct the myths of femaleness, and show us what we are really made of; blood, flesh, guts and all.

Live Flesh, Camilla Hanney, Shannon Bono & Paloma Tendero

At Sarabande Foundation, 4 to 8 March 2020

VISIT WEBSITE