Viking Bay, Broadstairs, 2014. From Funland by Rob Ball, published by Hoxton Mini Press

“As I’m standing here, a wee boat called the Merlin Two is coming in just as I’m watching the NorthLink ferry leave harbour. There is a rhythm that goes on, beyond the rise and fall of the tide, that covers so much activity. It’s fascinating what washes up. You can become absorbed in the activity of others and not just the elements of the sea. There is a joy, it is calming, but we are in the north here, we see it at its wildest too.”

I’m speaking on the phone with Neil Firth, director of the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness on the island of Orkney, which sits between the North Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean. As he gazes out his window across the dramatic Scottish coast, I’m looking out over the Channel in the Cinque-Port of Ramsgate, in the south-east of England, where my own wild rhythm that goes on beyond the rise and fall of the tide brought me here to live, seven years ago.

Firth is talking about the collection, donated by the late philanthropist Margaret Gardiner, and the relationship that the gallery has with the sea. “With artists in our collection, like Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, there is a continual balance between representation and reflection of the sea. But Margaret didn’t just want a place to display the collection, it’s a place where local artists can make work and do the same task as the pier itself—it’s about trade and exchange.”

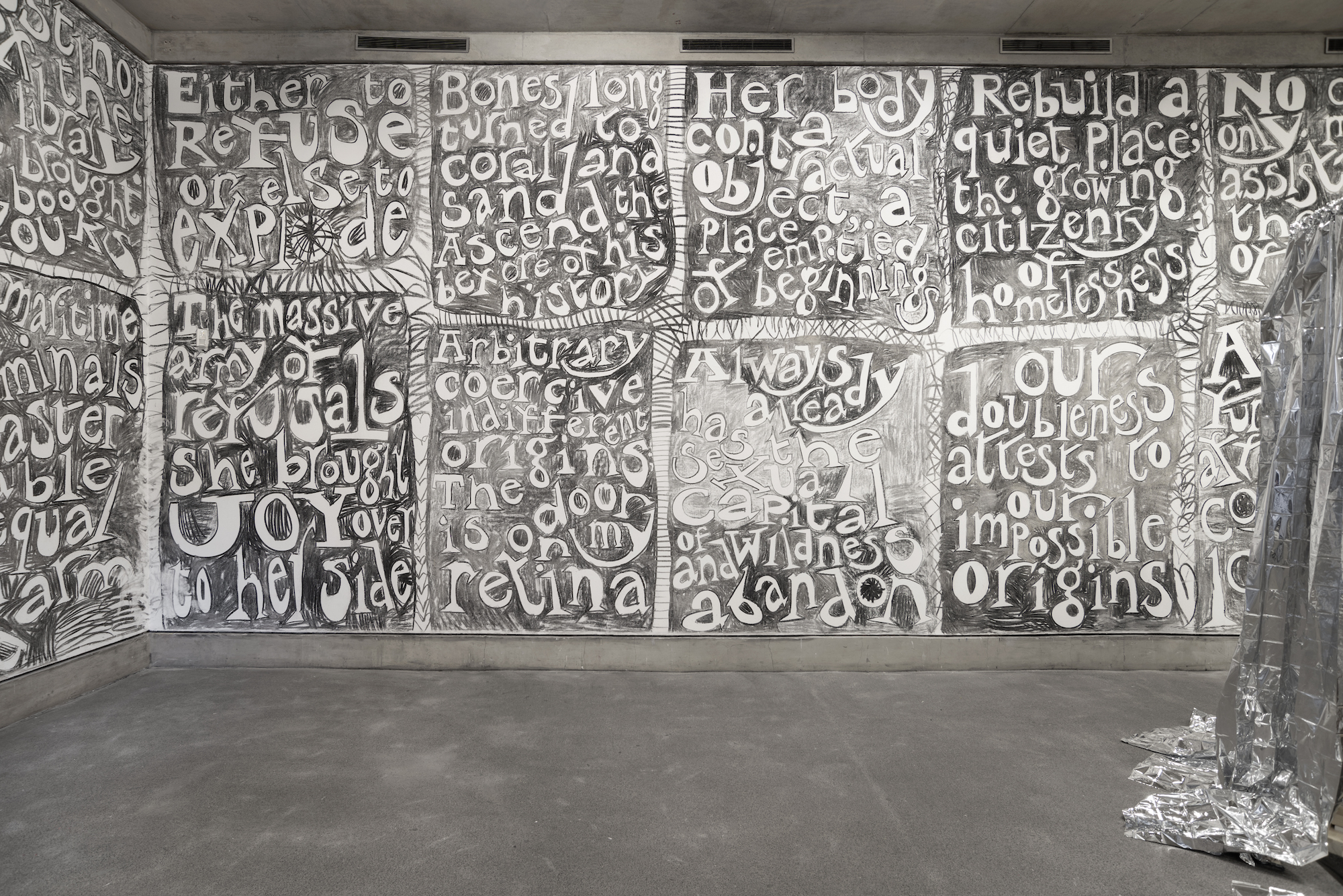

Instituting Care by Jade Montserrat

John Heffernan, senior curator at the Humber Street Gallery in Hull, a port city in North East England that was voted European City of Culture in 2017, shares the sentiment. “When it comes to the sea, we’re not putting on exhibitions of paintings of boats but instead exhibitions that touch on care, trade, food and prostitution.” The gallery also now houses one of the most iconic Hull former landmarks, the Dead Bod

—a simple drawing of an upturned bird—that was a piece of idiosyncratic homecoming graffiti for mariners. Brooding humour casts a line along the coast, in itself a form of cathartic pain relief from the horrors of the sea.

“ Despite the weekend supplements’ vanilla approach, for many, quality of life is not about craft beer, grammar schools and bargain Georgian townhouses”

Artist Jade Montserrat, whose exhibition Instituting Care recently travelled to the Humber Street Gallery from the Bluecoat Gallery in Liverpool, is currently undertaking a practice-based PhD on race and representation in Northern Britain in the context of the Black Atlantic. Montserrat identifies with the practice of self-care through her work.

“Care is the integral way to arrive at practice with critical race theory. [In my work], this ties to the landscape and the sea, as Liverpool was a main port for transatlantic slavery.” The Instituting Care exhibition digests Montserrat’s research and makes it visible in short texts that are applied to the walls of the gallery. There is a structure placed in the centre of the space, that, as she explains “…was collaboratively built so you could think about care in terms of a material structure. The emphasis isn’t on shelter, it’s on care for each other—and that care is structural.”

Dan Chilcott, founder of Resort Studios in Margate, an artist-run studio space for printmakers, filmmakers, designers and photographers, acknowledges the psychological benefits of creating by the sea. “A lot of work [made by the sea] touches on mental change, almost breakdown and re-establishment,” he considers. “There is time to consider the ebb and flow and constant change here; it’s in a lot of people’s work, whether you acknowledge it or not. Here, there is space to think.”

There is always something over the horizon for coastal towns. Beyond the lascivious middle-class property porn and come-hither travel blogs re-discovering faux-vintage, there is the very real need to balance work and life. The line in the sand is drawn far away from the coast; economic refugees from London are to be found nestling all along the south-east coast of Britain. Despite the weekend supplements’ vanilla approach, for many, quality of life is not about craft beer, grammar schools and bargain Georgian townhouses, it’s about simply being able to afford to be creative once more after serious financial assault by the city.

Much has been done along the coast from Margate. The ex-port town of Folkestone has reinvented itself, replete with a creative quarter and the UK’s “largest urban contemporary outdoor art exhibition”—the star-attracting triennale. Ioannis Ioannou, head of engagement at Creative Folkestone explains, “Instead of building a gallery and waiting for people to turn up, we decided to create a community that caters for people who are artists, makers and education providers. We want to create a new era and ecology.” The tide is turning, reversing the claustrophobic yearn from many youngsters born by the sea who try to escape. As Ioannou notes, “We’ve seen young people leave Folkestone to go away and study but now we see them coming back because they can see a future for themselves in the town. The identity of Folkestone now is driven by the arts, the demographics have changed.”

- Left: The Boating Pool, Ramsgate, 2010. Right: Promenade, Blackpool, 2018. Both from Funland by Rob Ball, published by Hoxton Mini Press

Away from the new industry of the former port, back in Margate, the highlight of the summer was Seaside: Photographed, Turner Contemporary’s first photography exhibition. Rob Ball, who exhibited in the exhibition—and works with curator Dr Karen Shepherdson (co-curator of the exhibition with Professor Val Williams of UAL London College of Communication) at Canterbury Christ Church University—tells me about the role of the sea from his home in Whitstable, along the coast from Margate. “I feel, in a creative sense, coastal communities are under-represented. I think it’s amazing that more photographers don’t take photographs of it. You are never more than seventy miles away from the coast in the UK,” says Ball.

What of the sea itself? “I think that if you are a visual person, having fifty per cent of your view unobscured, having the sea always close at hand for just that, is a rare and wonderful thing,” says Ball. But, he continues, “The whole seascape thing, as lovely as it is, I’m not sure what it tells us about our condition, it’s looked like that forever. If you turn the camera around, as I’ve done, stand on the shore, have your back to the sea, look at the seafront. I think that has been under-documented, and often sneered at as something that is just the stuff of day trips.”

“I think it’s amazing that more photographers don’t take photographs of it. You are never more than seventy miles away from the coast in the UK”

I wonder how personal this way of artist life is to Britain. “This is not just about the UK,” says Ball. “Coney Island in New York is such a great example of the looseness of the seaside. The rules are relaxed, the architecture is relaxed, it’s the same in Margate. It’s been sold fake promises, so things have happened organically. This is repair at the seaside; old things start getting repaired here.”

I myself am being repaired by the sea. The looseness of the seaside suits me. Dan Chilcott offers up a reason. “There is something in the cultural history of a seaside town: things that don’t happen in your average daily lives happen here. You go on holiday to be somewhere and someone different, you get this quirkiness, people are up for doing weird stuff, it’s like being at a festival.” Words from Orkney wash into my mind again, “There is a rhythm that goes on, beyond the rise and fall of the tide, that covers so much activity.”

Neil Firth is still stood, looking out of his window, “Orcadians enjoy the vista, the horizon is always a distance away. Closed in, you are often looking to where the horizon should be, at eye level some distance away. As an islander, the sea and the horizon is always there and it’s really quite comforting.” There is peace to be found in the creative activity along the coastal margins. And, wherever we are, there is always a horizon somewhere beyond.

This article originally appeared in Elephant Issue 40

BUY NOW