“This material is not about a region,” says The Gallery of Everything’s James Brett. Showing at their London space until 11 November, Art + Revolution in Haiti is a showcase of rare drawings, paintings, sculptures and objects by Haitian artists from a period of art history that traces the exchange at the start of what is perhaps the first truly global art movement: surrealism.

“It is about a context,” Brett continues. “It combines a mystical belief system, the world’s first black republic and the legacy of slavery. It is a twentieth-century revolution and speaks for a population who redefined their identity. Contrary to the categories of the past, there is nothing popular, primitive or naive about Haitian art.”

Art + Revolution begins in Haiti, at the Le Centre d’Art d’Haïti. Founded in 1944 in Port-au-Prince, the centre was a hotbed for radical art practices and staged exhibitions by artists who were mostly self-taught and who had strongly defined visions of Haitian and post-colonial identity.

It was at Le Centre d’Art that André Breton would encounter the Haitian artists who influenced his practice henceforth.

“Haitian painting will drink the blood of the

phoenix. And, with the epaulets of Dessalines, it will ventilate the world,” wrote Breton passionately in the guestbook of the Le Centre d’Art when in Haiti in 1945. The French author of the Surrealist Manifesto was visiting the Carribean island to give lectures on surrealism and Haiti—aimed at connecting surrealist art with politics in Haiti.

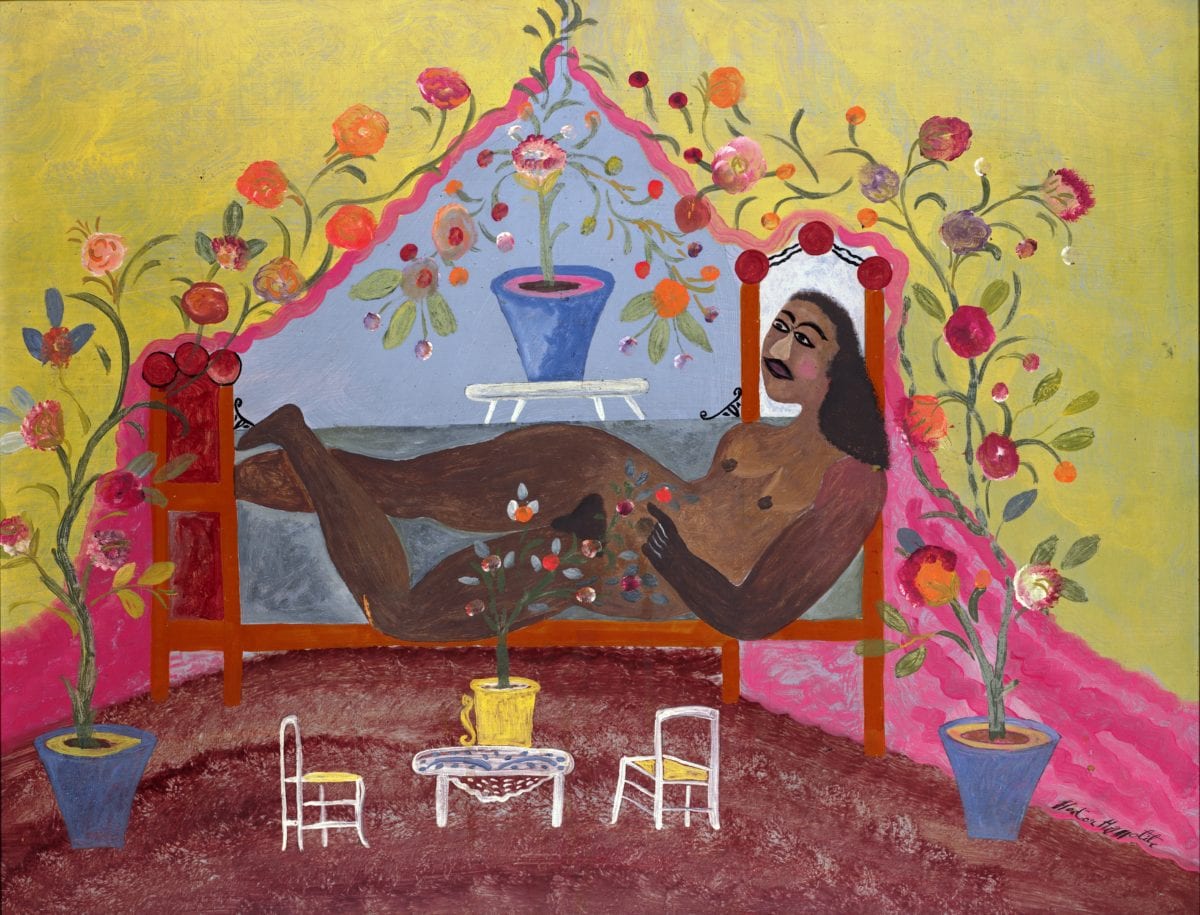

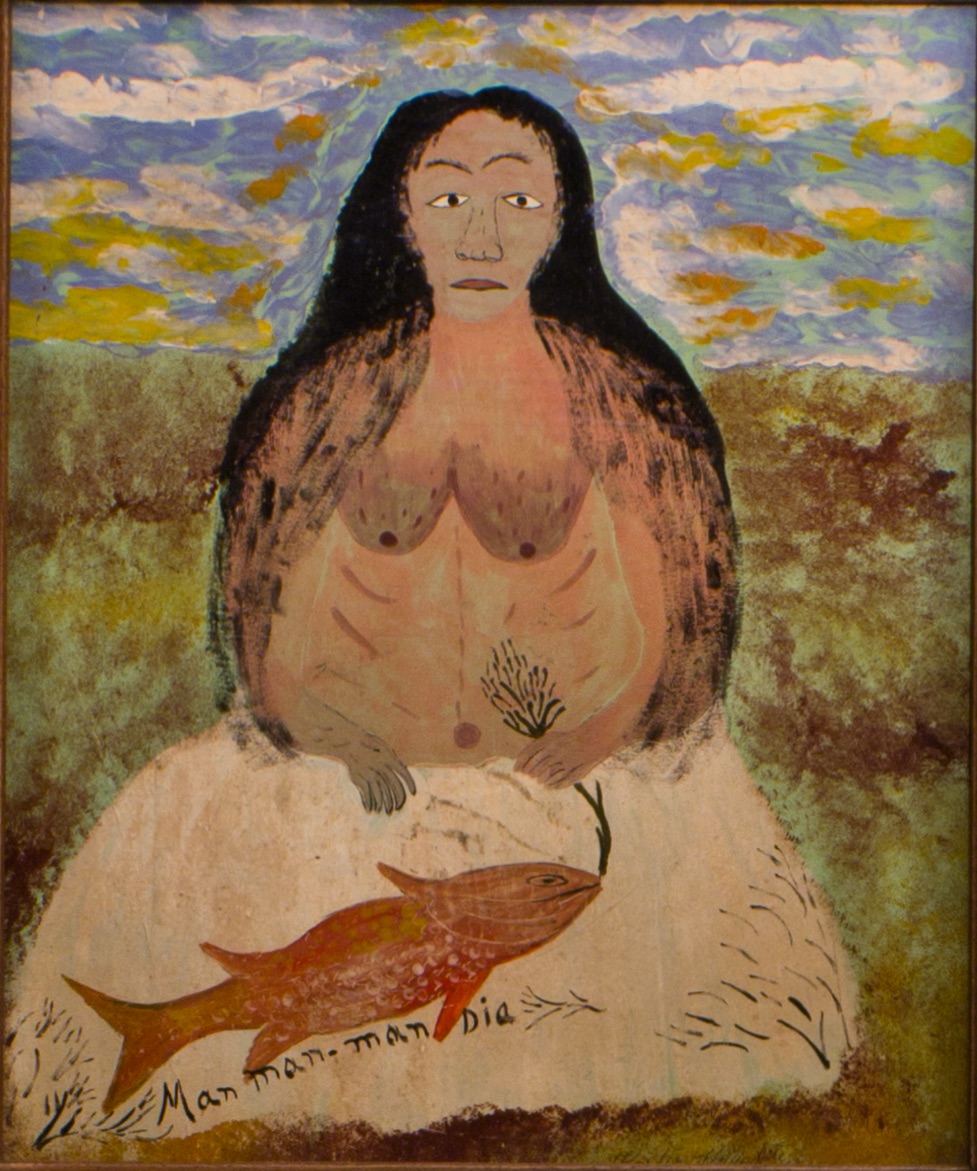

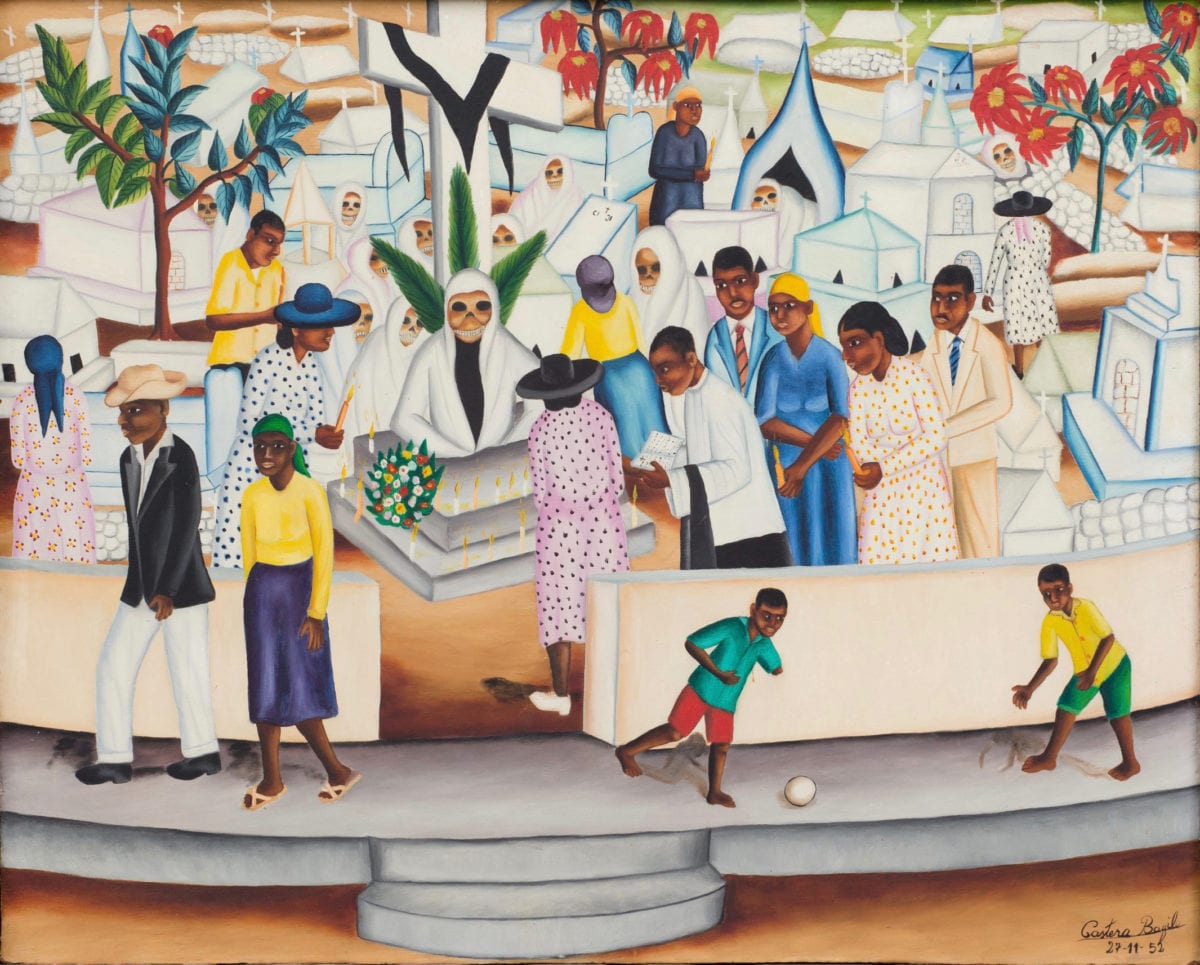

The paintings of Haitian painters, Hector Hyppolite, Castera Bazile, Philome Obin related to daily life experiences, but they were dramatic, metaphorical and fantastical, and also introduced references to Vodou rituals and customs, at a time when the Catholic church pervaded the country and the President was locking up Vodou priests, destroying temples and sacred objects. “In 1945, everything changed,” Brett notes. “Breton revived surrealism with the art of a proud Caribbean island.”

When he returned to France, Breton wrote continuously of the art he had seen in Haiti, and in particular of Hyppolite, with whom Breton shared no common spoken language. The Paris exhibition Surrealisme en 1947, organized in collaboration with Marcel Duchamp, was directly inspired by totemic themes in Hyppolite’s work, and tied surrealism to occultism more emphatically than before.