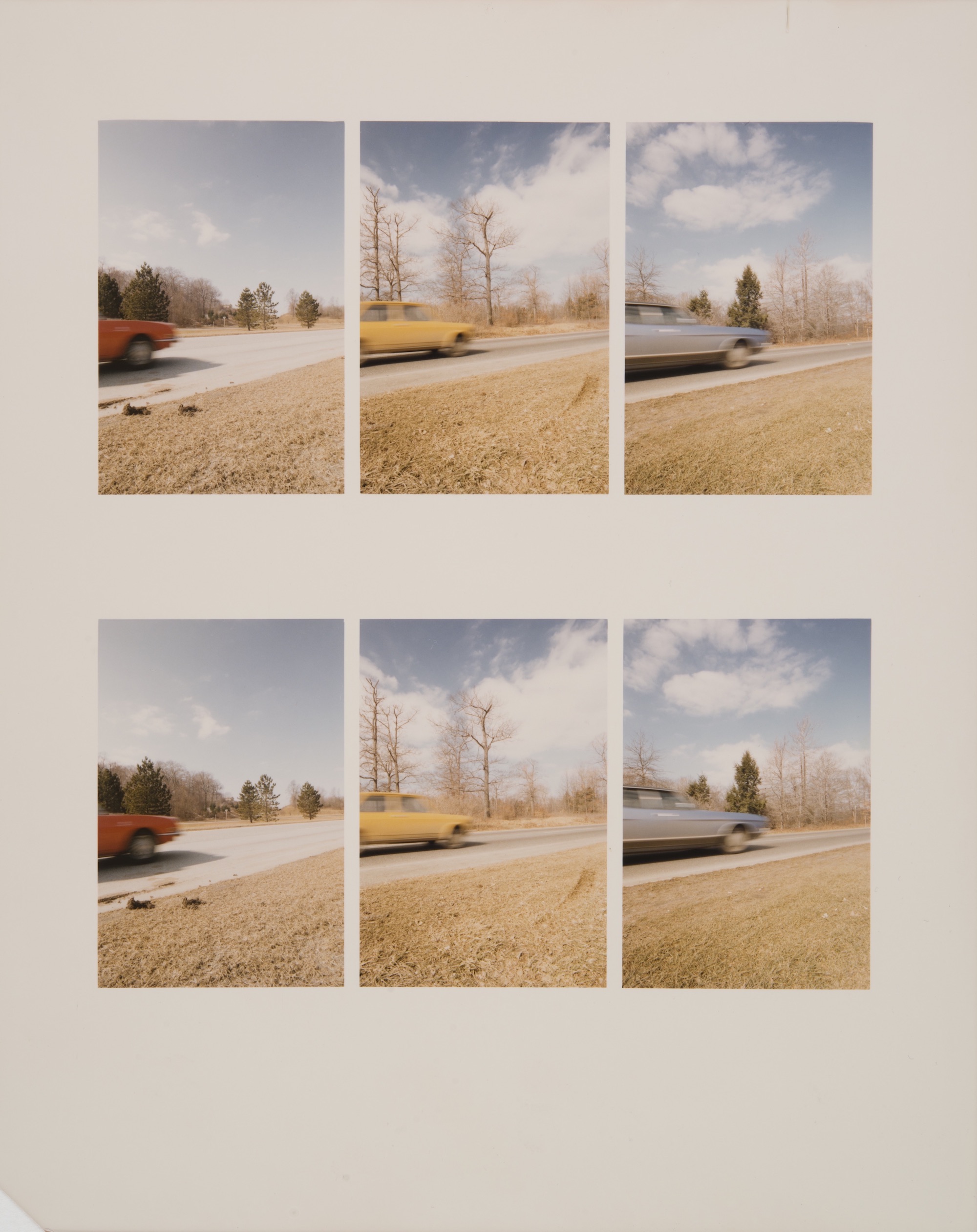

Four years after she first picked up a camera, Jan Groover made what she considered to be her first ‘serious’ photograph: 1971’s black-and-white diptych featuring two 24×36 contact prints positioned one above the other on a sheet of paper. Overhead is a cow in a field; below the same image appears with the cow disguised by a white rectangle block. It’s a calm image, one that asks the viewer to question the scope of the world around them.

“Negation or absence can’t be photographed, but the little diptych wasn’t really going for that,” remarked Groover’s husband, the art critic Bruce Boice, in a 1999 exhibition catalogue. “The idea was rather to show that the field is just as important as the cow.” Groover (who died in 2012) would employ this same thinking throughout her career.

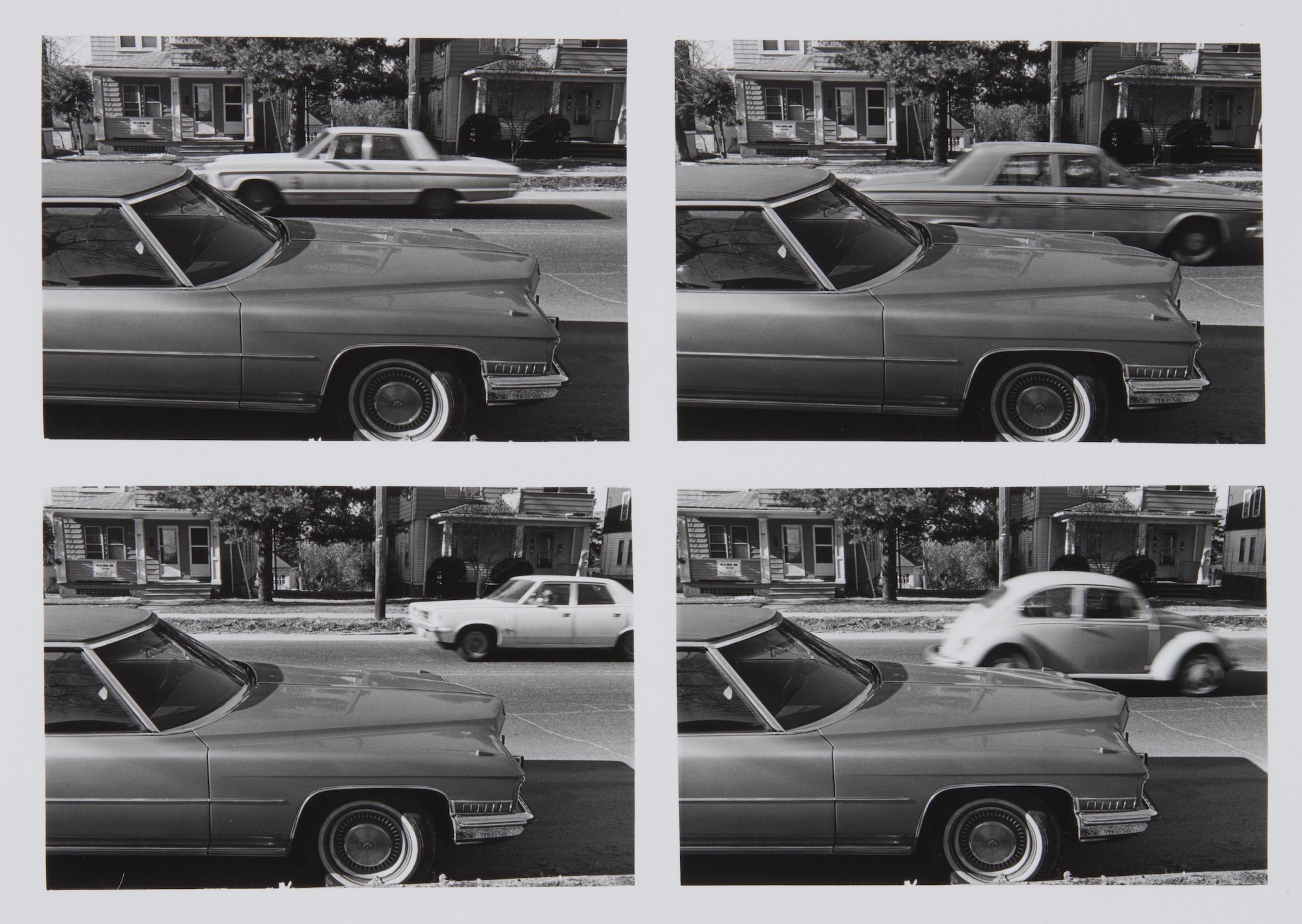

Trained as a painter (in 1965 she graduated from Pratt Institute with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting), Groover bought her first camera in 1967. She permanently adopted the new medium in 1971, later observing that “with photography I didn’t have to make things up. Everything was already there.” She followed the cow pictures with images of cars and trucks in motion, before arriving at the still lifes that would punctuate her future practice.

Maintaining a painter’s sensibility, Groover sketched out ideas before picking up her camera, and was indebted to artists like Giorgio Morandi, Cézanne and Caravaggio. “She does in photographs what people have traditionally expected paintings to do,” observed Boice in a 1994 documentary. “She deals with space.”

“For her, formalism was essential, so for her the subject does not matter,” says Tatyana Franck, director of the Musée de l’Elysée, which acquired Groover’s 20,000-piece archive in 2017. “What was important was that the viewer looks at her work in its entire composition and not focuses on what it means, meaning was not important.”

“With photography I didn’t have to make things up. Everything was already there…”

Unsure of how best to preserve the collection, Boice had been waiting for an acquisition by an institute such as the Elysée (Franck characterises as “like finding treasure”). It effectively rescued the work from the unwanted attention’s of Boice and Groover’s 18 cats.

Franck is also the co-curator of Laboratory of Forms, a major retrospective of the late photographer’s work, currently on display at Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna (MAMbo) as part of FOTO/INDUSTRIA, the city-wide biennale dedicated to the photography of industry and work. Focusing on food for 2021, this year’s iteration also includes work by the late Italian photographer Ando Gilardi, Manchester-based Mishka Henner, and Palestinian environmentalist Vivien Sansour. Within Groover’s space, a Morandi installation highlights the parallels between the pair’s practice.

Involved with a circle of friends that included the social landscape photographer Lee Friedlander and fine art photographer Ralph Gibson, Groover was celebrated in her lifetime. However in recent years the photographer’s catalogue has largely been neglected. Laboratory of Forms, which launched at Musée de l’Elysée in 2019 and will travel to Paris 2022, is set to change this.

Groover, asserts Franck, was a radical pioneer in every aspect of her work. She was notable for her early championing of colour photography as an artistic practice (marked by an image of hers on the cover of Artforum in January 1979), at a time when it was more commonly regarded as a commercial tool or amateur hobby. In addition to her own work, she taught the first colour photography course at Purchase College, SUNY, at which Laurie Simmons was a pupil.

“She does in photographs what people have traditionally expected paintings to do”

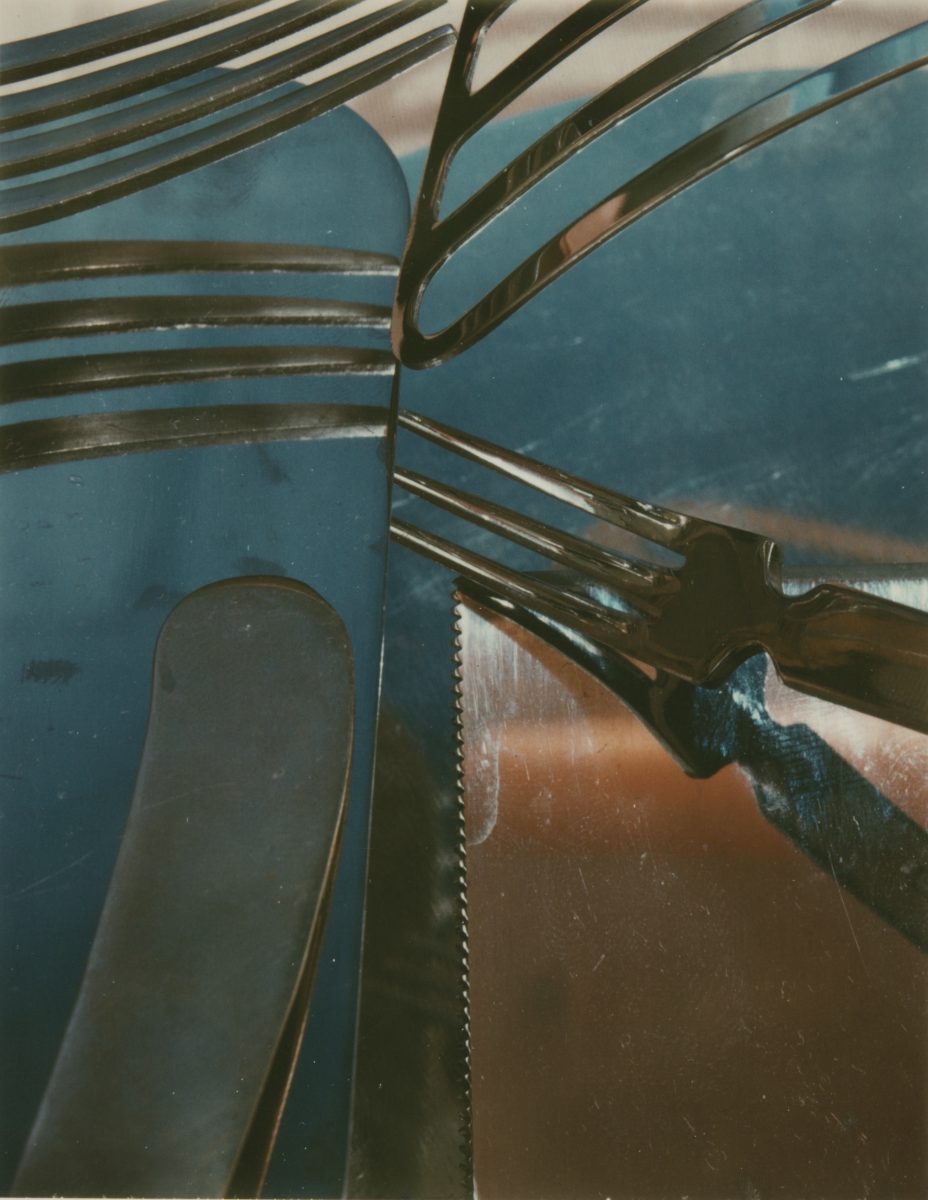

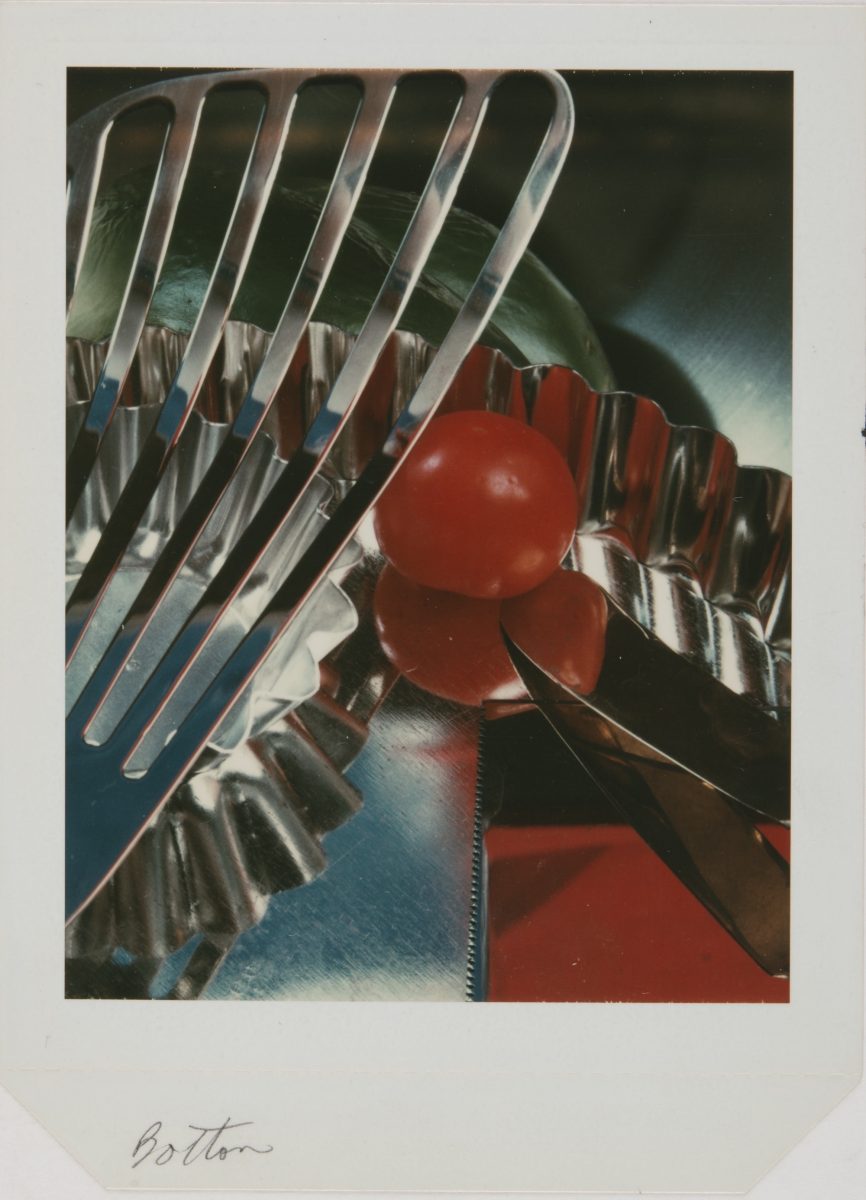

In 1977, Groover embarked on what would become her most acclaimed project: the Kitchen Still Lifes. The series, later exhibited at New York’s Sonnabend Gallery, saw Groover replace the traditional still life fixtures of 16th and 17th century Dutch art (mammoth floral bouquets and symbolic fruits), with cutlery and utensils. Photographed close up in her kitchen sink, plant leaves would occasionally glow against the reflective metals in the images.

Unlike other artists who have used the kitchen’s domestic affiliation as a vehicle for work with a feminist principle—Carrie Mae Weems’ The Kitchen Table Series (1990) or Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975)—Groover was adamant her work’s genesis was not underscored by such a motivation. The instruments were instead chosen for their visual properties.

“She was not necessarily a feminist, but I think you can put anything you want on what she’s done,” says Franck, acknowledging the potential readings of the work. In 2021, it’s hard to separate the pieces from a feminist gaze, so consumed are the images by objects typically associated with traditional women’s work. That Groover’s peers were mostly men only further couples her with this political stance. “In producing art, it was a way of saying ‘I don’t care, I do what I want’, but for her what was important was transmission,” Franck continues.

“Nearly a decade after her death, Groover’s influence can again be felt infiltrating the work of contemporary photographers”

A series of tabletop still lifes arrived next. This time produced in her studio and with items placed on faux Greek columns, here Groover created tableaus of fruit, shells and bottles. In 1987 a MoMA retrospective introduced her to a wider audience, with a review in The New York Times suggesting that “Jan Groover’s artistic career has been a barometer of the recent fortunes of photography within the art world.” In 1988 a further exhibition review from the same paper noted, “Jan Groover proves once again why she is among the most fascinating and challenging photographers of her generation.”

Why, then, did Groover not continue on the same upward trajectory? In 1991 she moved to France with her husband, a reaction to George HW Bush’s presidential win in 1988, leaving behind their close group of intellectuals, artists and museum directors, instead embracing near anonymity in the village of Montpon-Ménestérol. Barely able to speak the language and with little desire to engage with the Parisian art scene, she began to slip into obscurity. A 1994 documentary, Tilting at Space

, which surveyed Groover’s work and practice, failed to change this.

Nearly a decade after her death, however, Groover’s influence can again be felt infiltrating the work of contemporary photographers, many of whom are active on Instagram. From the rich palette of her 1980s still lifes to the sometimes claustrophobic nature of her kitchen close ups, as well as her distinct consideration of visual arrangements, photographers such as Maisie Cousins, Polly Brown

and Molly Matalon have all paid tribute to her influence on their own work.

With the Laboratory Of Forms show further amplifying Groover’s work and providing new opportunities to engage with her practice, the artist might finally now be getting the attention she deserves.

Zoe Whitfield is a UK-based freelance writer

All images courtesy Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna

Jan Groover: Laboratory Of Forms

Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, until 2 January 2022

VISIT WEBSITE